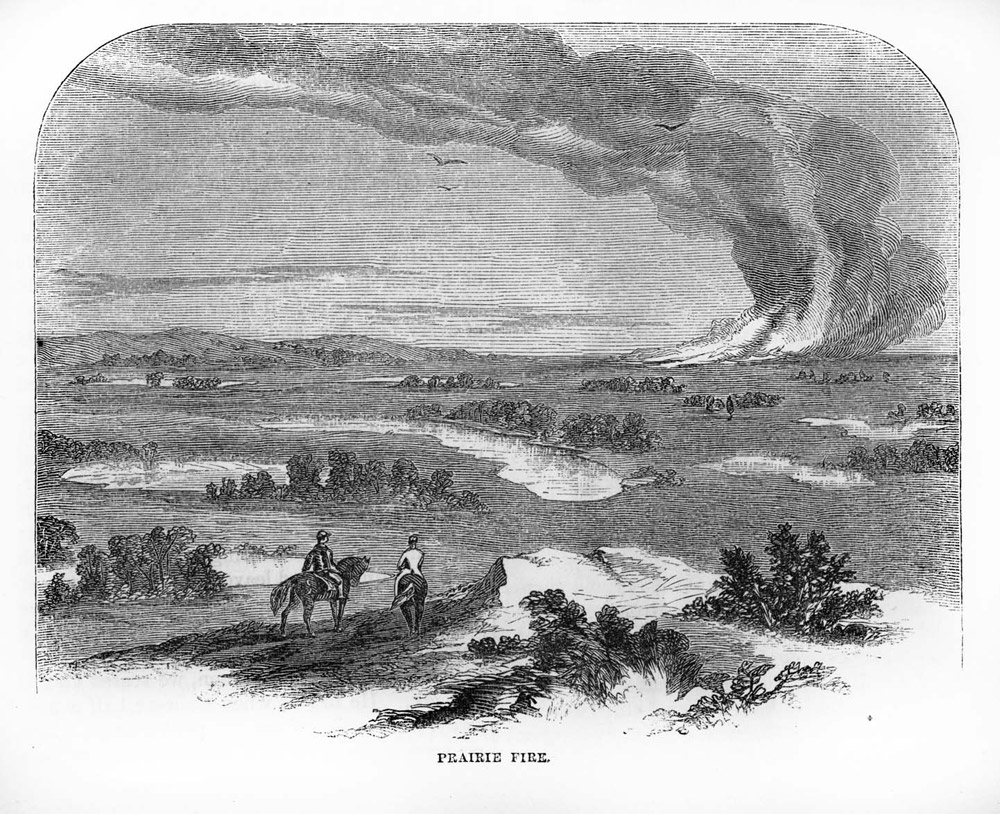

Prairie fires were common in North Dakota before roads and farm fields interfered. The dry prairie grass burned easily. Hot, dry summer and fall seasons left the prairie open to fire. Many prairie fires also occurred in the spring when the snow had melted, the grass had not yet begun to turn green, and the wind was likely to blow daily.

Fires were sometimes caused by lightning, but there is evidence that many fires were started accidentally by careless people. If the grass was dry and the wind was blowing, a small campfire could quickly rage out of control.

The earliest European American explorers and traders were convinced that most prairie fires were set by Indians. Indians used fire to drive whites out of their country. The smoke from fires could also be used to cover the retreat of families in case of attack by enemies. Small fires might be used in the spring to hasten new grass growth and draw more game to the area. By burning the tall grasses off, hunters could more easily spot game animals.

However, fires late in the summer would possibly drive bison away. Without rain, the grasses would not grow. Bison herds would move on to find better feed. Late summer fires, when traders and Indians were trying to get meat for the winter supply, could be devastating. If the bison left after a fire, and did not return, the people faced starvation. Fire also destroyed grasses that horses fed upon.

Some explorers believed that prairie fires prevented the Great Plains from being forested. (See Image 3.) This was a false conclusion because rainfall was the most important factor in determining the kind of plants that grew on the plains. However, some of the trees that grew near rivers could withstand fire because they had thick bark. Aspen trees did not have such thick bark and were damaged by prairie fires.

It was possible for a prairie fire to have such intense heat, thick smoke, and wind-driven speed that bison and horses could not escape the flames. Fur trader Alexander Henry the Younger wrote in his journal of seeing bison blinded by prairie fire and their great masses of wooly hair singed. Occasionally whole herds were killed by fire.

Throughout the early nineteenth century, the numbers of bison declined steadily. Fewer bison meant that dried grass made more fuel for wild fires. Therefore, it is likely that as American traders, soldiers, and finally settlers entered the region, they experienced more prairie fires than did the American Indians who had lived here for thousands of years. This increase in the number of prairie fires probably only lasted a decade or so. The number of fires was reduced, but never eliminated, by farm fields and roads.

Why is this important? Fire is part of the ecology of the grasslands. Grasses thrive when the old thatch is periodically burned off. However, in the nineteenth century, fire quickly raged out of control. Fire was dangerous for wild and domestic animals and could cause hard times for people who depended on bison and other grazing animals. However, people found ways to take advantage of fire or to avoid its negative consequences.

Explorers and traders sent reports on the northern Great Plains back to eastern newspapers and publishers. Their stories of prairie fires helped to enhance the national image of the northern Great Plains as a drought-ridden and dangerous place to live.