One of the ways we learn about the past is to study material culture. Usually, culture is thought to be things we cannot touch. Language, religion, marriage customs – these are some of the qualities of a culture. But people also make, purchase, steal, trade, and use three-dimensional objects. We refer to these objects as material culture.

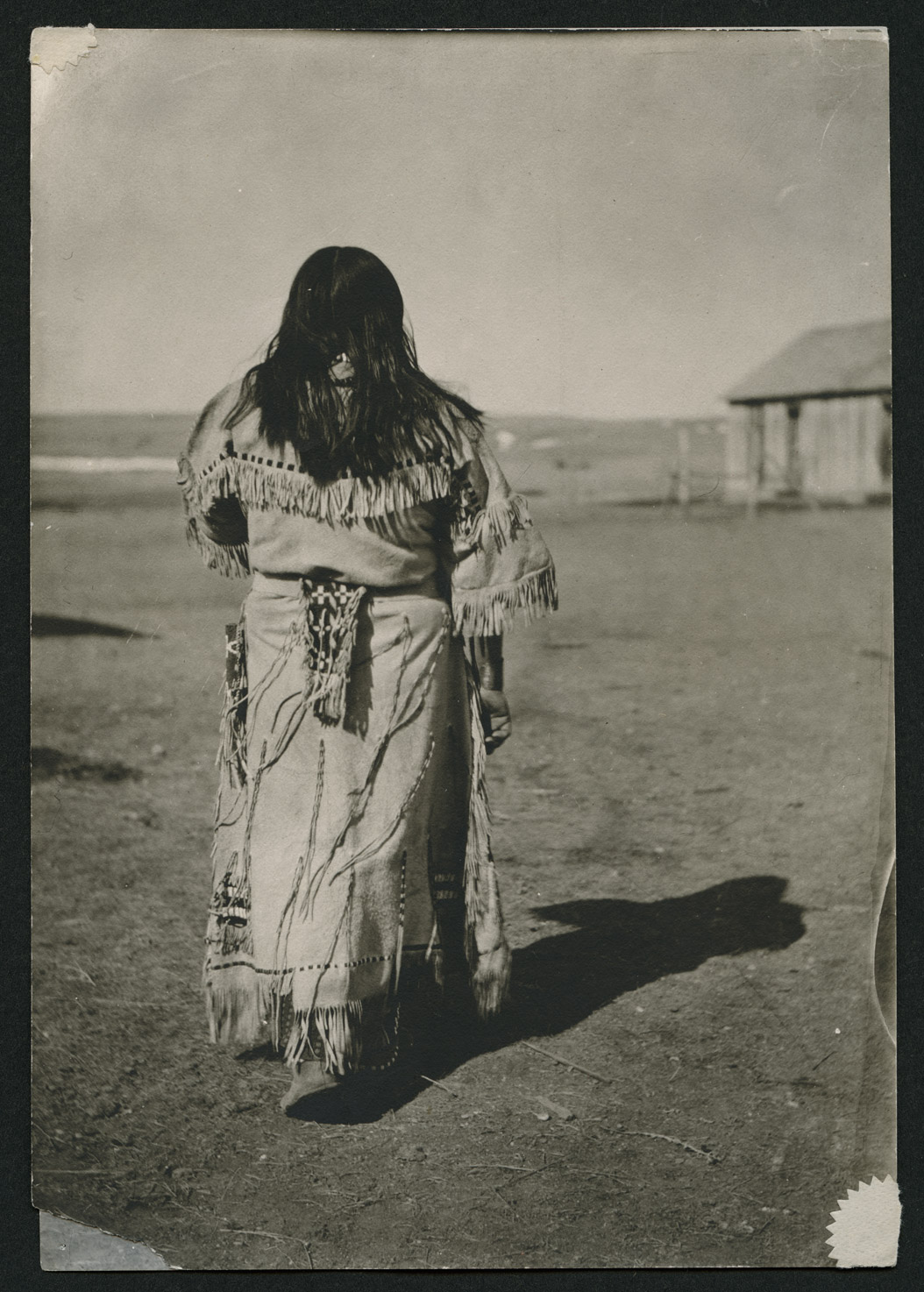

Charles Ward Hoffman was one of the important collectors of Indian-made objects in North Dakota. Hoffman and his wife Carolette presented their collection of 75 pieces made by Hidatsas, Mandans, and Arikaras to the State Historical Society of North Dakota museum in 1907. Hoffman's life story adds importance to the collection.

Charles Ward Hoffman was born in 1868 at Like-A-Fishhook village on the Fort Berthold reservation. His mother was descended from Arikaras and European American traders. Her name was not recorded. Hoffman’s father was a trader named Charles Wheeler Hoffman. Charles Hoffman (the younger) was named Ni-ku-ta-wi-ksu-ta-ka (White Hawk) by his mother’s Arikara family.

When Ni-ku-ta-wi-ksu-ta-ka was still a baby, his father went East on a trading trip. The baby’s Arikara family took him and his mother into their protection. When Charles Hoffman (the elder) returned, he was told that his wife “had deserted him, and that his son was dead.” Hoffman was unhappy, but he moved on to Montana. His Arikara wife grieved for him and died young. (Much later in his life, Charles Hoffman was re-united with his father and they maintained a good relationship.)

Ni-ku-ta-wi-ksu-ta-ka was cared for by his mother’s relatives. At an early age, he started to earn money by working at the Fort Berthold mission. Reverend Charles L. Hall paid Ni-ku-ta-wi-ksu-ta-ka 50 cents a week to lead the missionary’s milk cow to water. When this job brought him into contact with Hidatsa boys who thought it fun to throw sticks and stones at the cow and him, he quit the job. He didn’t have another job until he was 16.

In between jobs, Charles attended school. He attended the government boarding school at Fort Stevenson. In 1885 he went to Santee, Nebraska where he attended the Congregational boarding school. The Santee school specialized in preparing American Indian students to become teachers. In 1890, he went to Kimball Union Academy at Meriden, New Hampshire. Kimball Union Academy was not an Indian Boarding School. Students educated at Kimball Union were encouraged to enter the ministry. All students were given a good liberal arts education. Hoffman graduated in 1894 at the age of 26.

Hoffman briefly returned to Fort Berthold, but then went to Santee Normal School to teach. There he met Carolette Smith, a non-Indian teacher. They returned to Fort Berthold and married in 1895. Hoffman worked in a store for a while; then he and Carolette opened a school at Shell Creek village. The Hoffmans taught there for 23 years and another three years at Independence. Later, Charles Hoffman became a farm supervisor for the Fort Berthold agency. When he retired in 1933, Charles Hoffman was given the honorable name, Rising Bear.

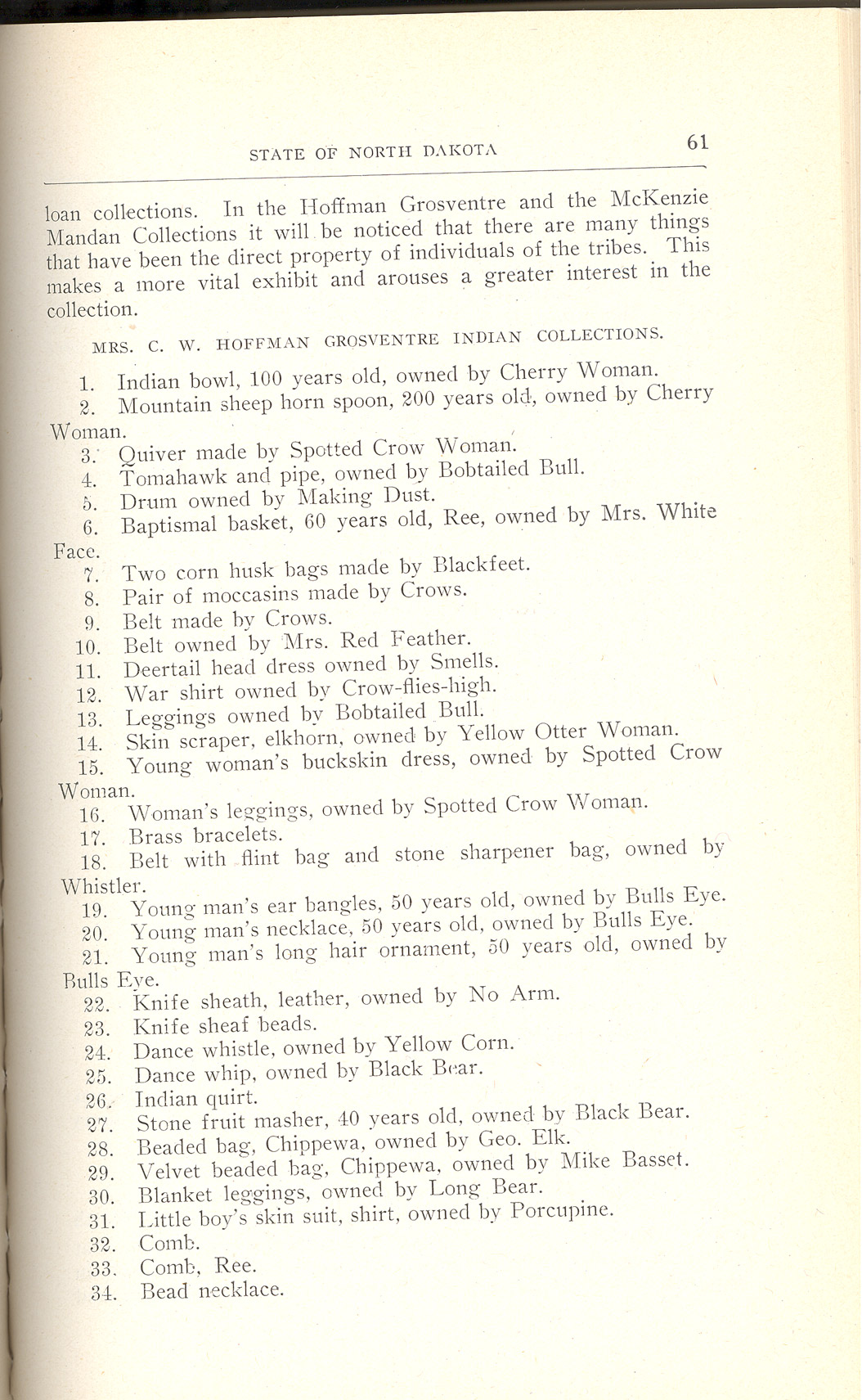

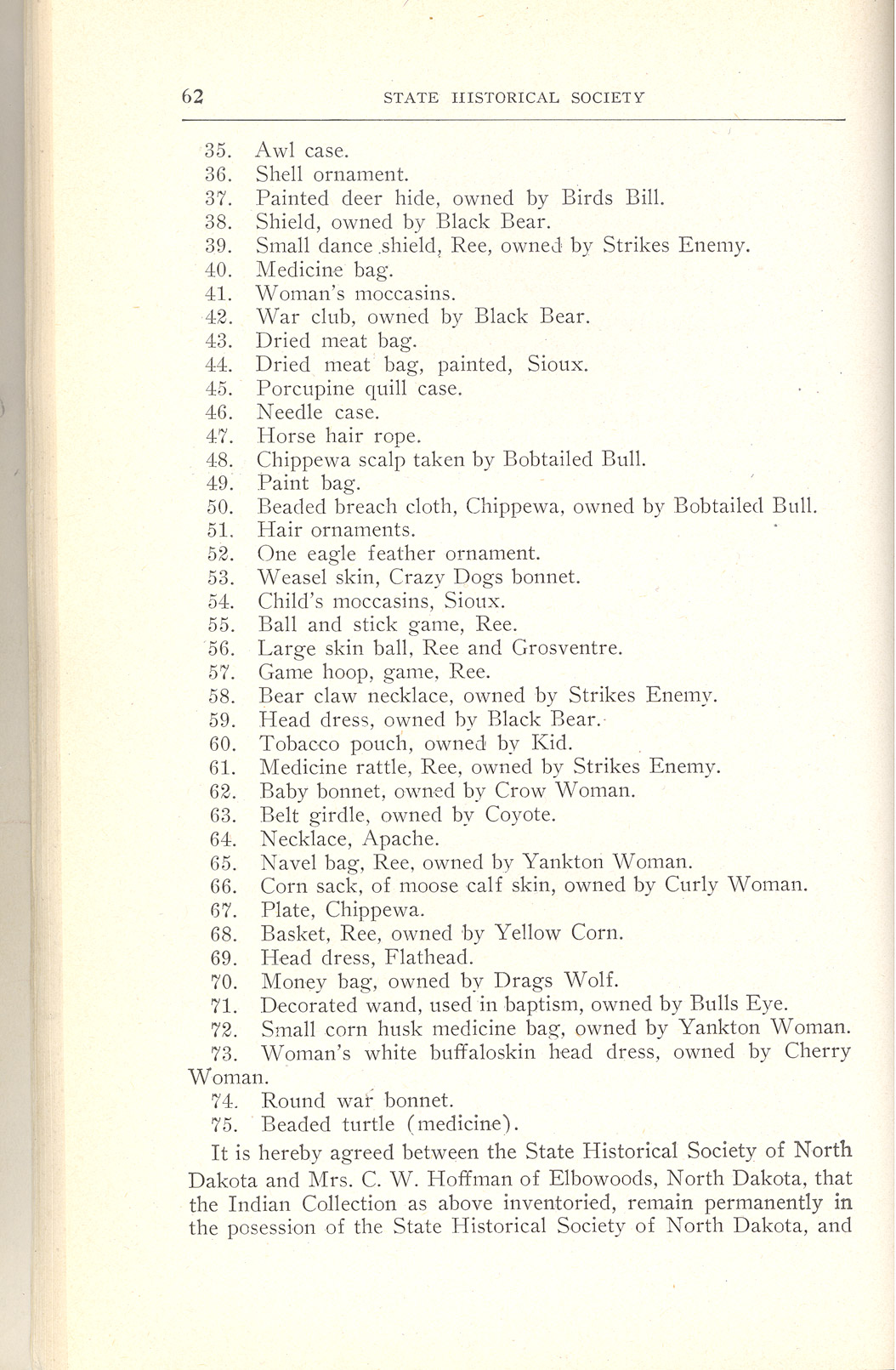

In 1907, Charles and Carolette sold a collection of 75 objects to the State Historical Society of North Dakota. The objects were collected by the Hoffmans during their years of teaching on the reservation. The collection has been called “one of the best in existence.” (See Document 6)

Why is this important? Many objects made by American Indians have been purchased by or donated to the State Historical Society museum. Some are on display where they help visitors understand the complexity of American Indian tribal life. Other objects, particularly if they are fragile, are kept in museum storage. These will be used for special exhibits or study.

The objects collected by Charles and Carolette Hoffman have preserved the material culture of the Hidatsas, Mandans, and Arikaras who lived at Fort Berthold in the late 19th century. The objects enhance our knowledge of the skills, artistic values, social relationships, and economies of the tribes in a time of transition.

Erling Nicolai Rolfsrud, “Rising Bear, Pioneer North Dakota Schoolteacher,” North Dakota History vol. 19 no. 4 (Fall 1952): 241-249.

Orin G. Libby, “Mrs. C. W. Hoffman Gros Ventre Indian Collections,” Collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota vol. II (1908): 61-63.

The Adoption Ceremony

Among the objects Charles and Carolette Hoffman presented to the State Historical Society in 1907 was an adoption basket. (See Image 12) This basket, made of rush and decorated with dyed gull quills (the strong center of the feather), was used in the Mandan and Hidatsa adoption ceremonies.

When a man or a woman wanted to adopt another person into their clan, they would follow a ritual that involved gifts and feasts. Both the adopter and the adoptee gave gifts to the other person and presented the other person with a feast. Usually, the entire family of the adoptee was included, so about six people would be adopted by one person.

The person being adopted gave good buffalo horses to the adopter. The adopter gave beautifully made and decorated clothing to the adoptee. The ritual involved other members of the clan who told their stories and helped the adopter prepare for the ritual. All the members of the village would come by the lodge where the ceremony took place to see the quality of the gifts. Each person who was adopted could eventually adopt four more people into the clan.

One part of the ceremony was to “wash” the adoptee with water that dripped through the basket onto the adoptee’s head. (See Image 13) The water was dried off with a “wildcat’s hide” (perhaps a mountain lion or a bobcat). Because this part of the ritual was similar to Christian baptism, the ceremony is often called baptism, and the basket is sometimes called a baptism basket.

The basket was also sometimes used for playing the shawe (SHA-way) game. The basket itself was not sacred, though the pipes used in the ceremony were considered sacred and used only for important ceremonies.

Why is this important? The basket for the adoption ceremony reminds us of the ways in which the Mandans and Hidatsas maintained their communities. They chose to bring people into their families and clans by adoption. In this way, they made close ties around the village that extended beyond their biological families. A person’s reputation in the village was made better (or worse) by the quality of gifts exchanged. A poor gift would have people talking about him or her in an unkind way.

This adoption ceremony was probably the one used when Gilbert Wilson was adopted into the Prairie Chicken clan. We can assume that he was not able to give buffalo hunting horses to Buffalo Bird Woman. However, because this was a very important ceremony, he probably gave her some very important gifts.

Alfred W. Bowers, Mandan Social and Ceremonial Organization (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1950 (2004).

Sacred Objects

Curators, the people who take care of the objects in a museum’s collections, are concerned about how to care for sacred objects. When a congregation decides to close a church, some items from the church might be donated to the State Historical Society of North Dakota (SHSND.) Of course, this only happens with the permission of the congregation, and in the case of some denominations, with the permission of the “mother church.” The mother church is usually the national or world headquarters of that denomination.

If a Catholic congregation offers an object from its church, the object is secularized before it can be taken from the church. This ritual of secularization removes the sacred qualities of the object. It becomes simply an object that represents the religious rituals of a group or a congregation.

Some objects used in sacred ceremonies can never be secularized. Those objects do not become part of a museum’s collection. For instance, the torah, the sacred text of Jewish congregations, cannot be secularized. The SHSND museum collection includes some torah covers. Torah covers are usually made of beautifully decorated fabric. These torah covers are not sacred, but were used to protect the sacred text.

Sacred or spiritual objects related to American Indian spiritual practices have been donated to the SHSND. Some scholars would state that all objects made and used by American Indians had spiritual significance to their owners. However, scholars agree that certain objects called sacred bundles, or medicine bundles, are the most important of the religious objects that American Indians used. These can never be secularized. The sacred power of the bundle never fades and cannot be removed by ritual.

Some sacred bundles became part of the collection at the SHSND during a time of cultural disruption on reservations. The museum is the present caretaker, not the owner, of a few sacred bundles. The State Historical Society houses the sacred bundles for the tribes with their knowledge and guidance.

Curators treat all religious objects with great care and respect. Each object is stored or displayed in such a way that it is protected from physical harm.

Why is this important? There are several important reasons to include some religious objects in a museum that represents a number of cultures. Sacred objects often demonstrate exquisite artistic skill and design. Even in the poorest of pioneer communities, a congregation tried to have a beautiful altar in the church.

Early pioneers of North Dakota turned to faith to help them establish their new homes, towns, and farms. Faith helped them through the difficult years. Their churches were the hub of the communities. Historically, the churches and the objects that served the congregations are reminders of the spiritual, moral, and social qualities the pioneers brought to their communities and state.

Sacred objects are preserved to remind us of the variety of religious experiences in our state. One of the great freedoms of the people of the United States is the right to worship as we please. A collection of sacred objects reminds us that the generations of people who came before us were deeply attached to their religions.

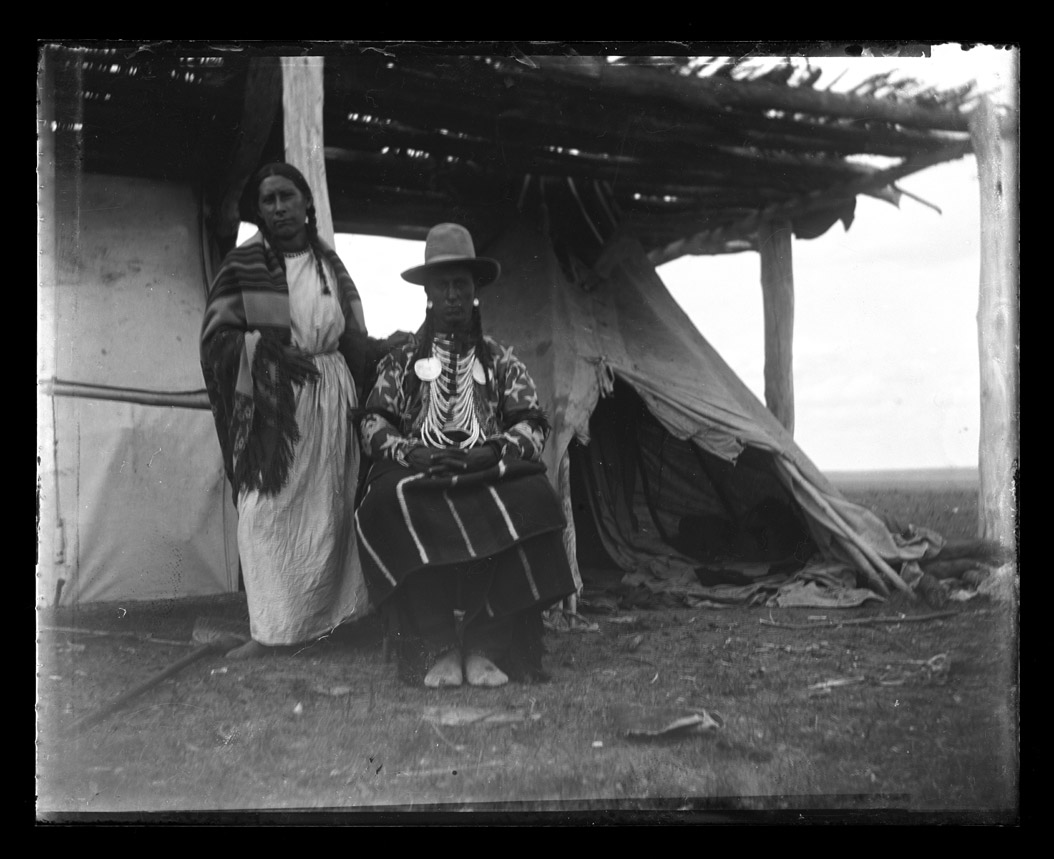

Photo Essay: The Hoffman Collection

These objects are just a few of the pieces donated by Charles and Carolette Hoffman. These objects are housed in the State Historical Society of North Dakota.