Linda Slaughter, Historian

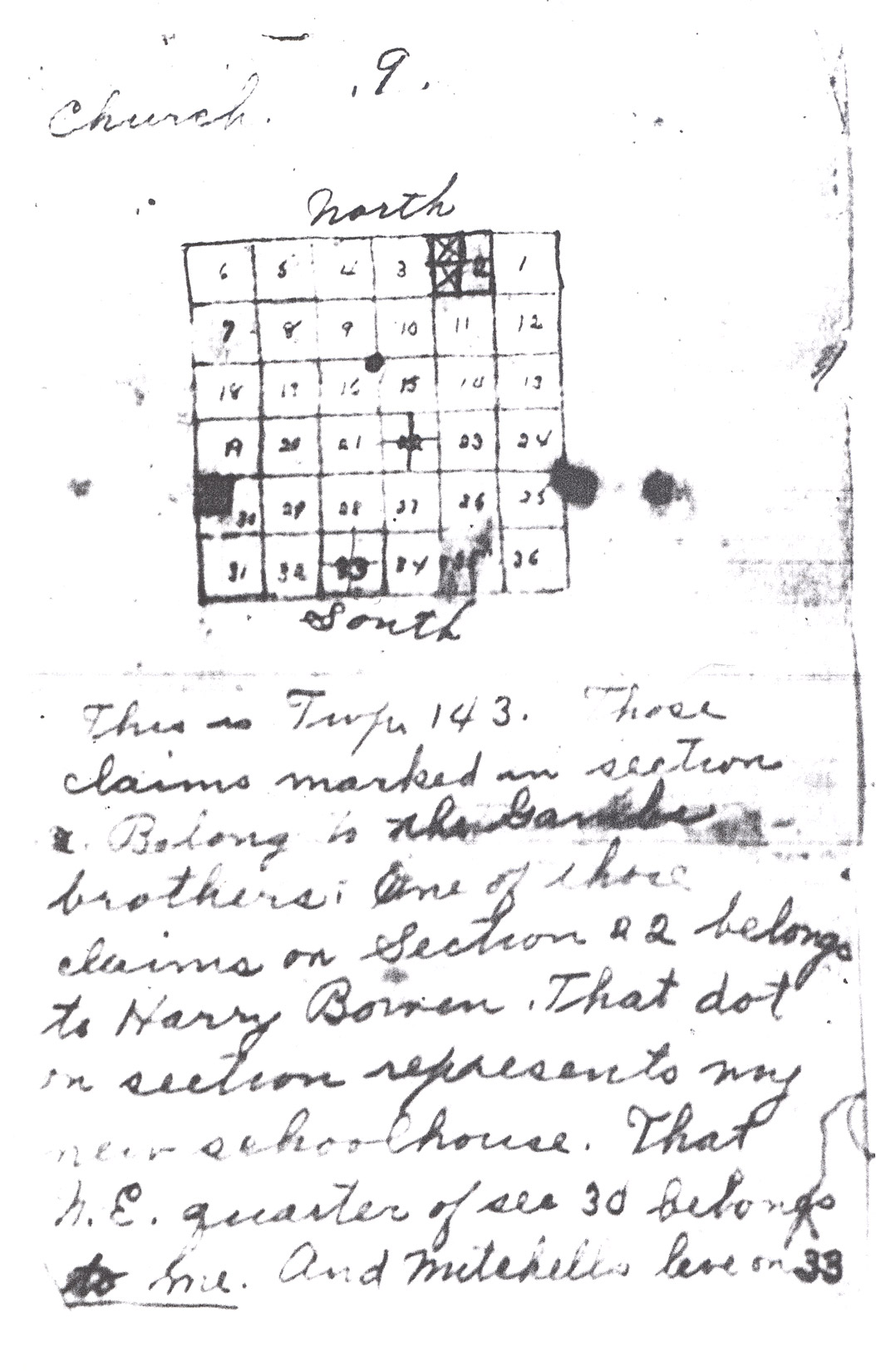

On February 15th, 1874, 1,200 people lived in Bismarck, Dakota Territory. There were 300 buildings in the town that one year earlier had comprised only a few Army tents and a few log cabins. Bismarck’s economy was growing rapidly. (See Image 5) Businesses included

6 Hotels, 18 Saloons, 2 Shoe Stores, 1 Hardware Store, 1 Tin Shop, 1 Jewelry Store, 3 Billiard Halls, 2 Blacksmith Shops, 1 Bowling Alley, 3 Livery Stables, 3 Meat Markets, 1 Drug Store, 2 Bakeries, 2 News Stands, 3 Barber Shops, 1 Bath, 1 Confectionery, 2 Liquor Stores, 1 Brewery, 1 Bookstore, 1 Gunshop, 5 General Stores, 3 Restaurants, 3 Carpenter Shops, 4 Warehouses, 2 Churches, 1 Telegraph Office, 1 Newspaper, Book and Job Office, and one Parsonage.

SourceThis description was taken from Linda Slaughter, The New Northwest. Though Linda Slaughter wrote a rather fanciful “history” of the region, this document gives us a very good early view of the town long before it became the state capital. Read the entire pamphlet at http://archive.org/details/101221443.nlm.nih.gov

Linda Slaughter, http://archive.org/details/freedmenofsout00slau

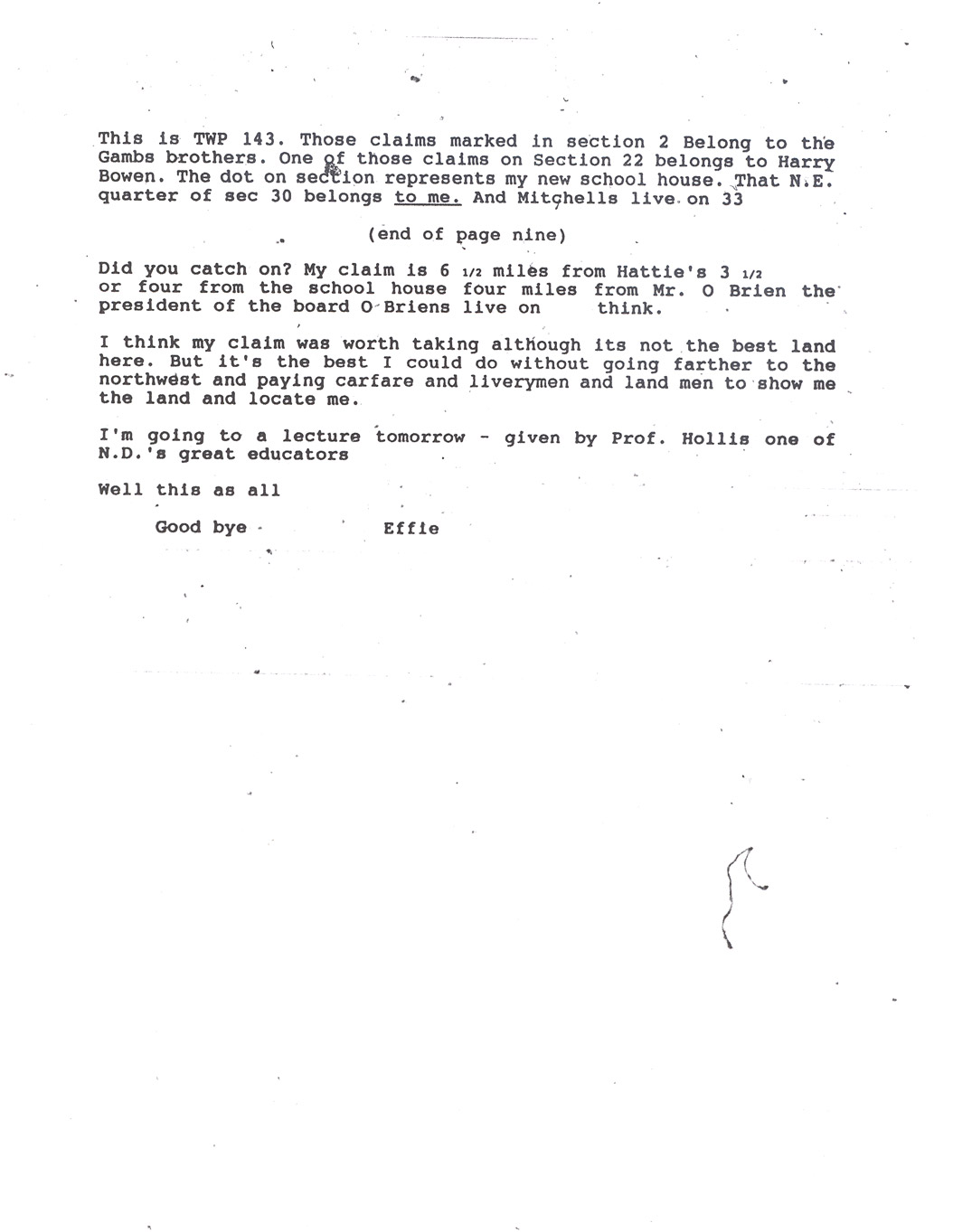

This snapshot of Bismarck’s first year is part of the historical record. The author of this paragraph, Linda Slaughter, wrote this description of her little city for a pamphlet called The New Northwest that was designed to draw newcomers to Burleigh County. Slaughter, an experienced writer and historian, brought a historian’s way of thinking to all of her writing. (See Image 6)

In addition, Linda Slaughter knew that she lived in historic times. Her husband was a veteran of the Union Army in the Civil War and had served at Fort Rice and Camp Hancock. The Slaughters participated in the founding of a new town (Bismarck) in Dakota Territory. The Slaughters believed that Dakota presented excellent opportunities for themselves and their three daughters. They also knew that they were participating in the important historical process of white settlement on the northern Great Plains.

Linda Slaughter continued to act as an historian of the region. She organized the Ladies’ Historical Society of Bismarck. At statehood in 1889, the group added “and North Dakota” to their title. Slaughter made personal visits to encourage women to become members of the Historical Society. Gladys Pearce, an early settler, remembered Linda Slaughter as the “literary type” and thought that she had nothing in common with Slaughter. Mrs. Slaughter, however, persuaded Mrs. Pearce that “the history of Bismarck and of this state in fact would depend upon those people who had lived it.”

The Ladies’ Historical Society gathered documents and preserved them. There was no archive or museum, so Mrs. Slaughter kept important papers at her home. She later wrote: “I had kept not alone the military orders . . . , but a file of orders of equal interest from a historical point of view.”

When the Ladies’ Historical Society of Bismarck and North Dakota merged in 1895 with the brand new State Historical Society of North Dakota, Slaughter wrote a brief history of her organization. She concluded that

The Ladies of the Historical Society of Bismarck and North Dakota have done their work. The North Dakota Historical Society takes up the work where they have laid it down. That the work will be well done, I have not a doubt.

Why is this important? Whenever people keep records of their present activities, they are providing the people of the future with the information they need to understand their past. Linda Slaughter was aware of both views of history, from the present looking forward and from the future looking back.

Slaughter identified military history (“military orders”) as important. She collected military records and wrote the military history of Dakota Territory. However, her other records, such as the list of businesses in Bismarck provide an “accidental” history or record of the early stages of a frontier town. Both resources are important to modern historians.

The State Historical Society of North Dakota

In 1894, Clement Lounsberry suggested organizing the State Historical Society of North Dakota. Lounsberry had come to Dakota Territory in 1873 with the intention of starting a newspaper. In July, 1873, he published the first edition of the Bismarck Tribune. Lounsberry lived in North Dakota throughout much of the history of the young state, and understood the importance of preserving its history.

One of Lounsberry’s allies in this process was Linda Slaughter of Bismarck. She had organized the Ladies’ Historical Society of Bismarck many years before. With several other friends and supporters, Lounsberry and Slaughter put together an organization that had little to do other than talk about what they might do.

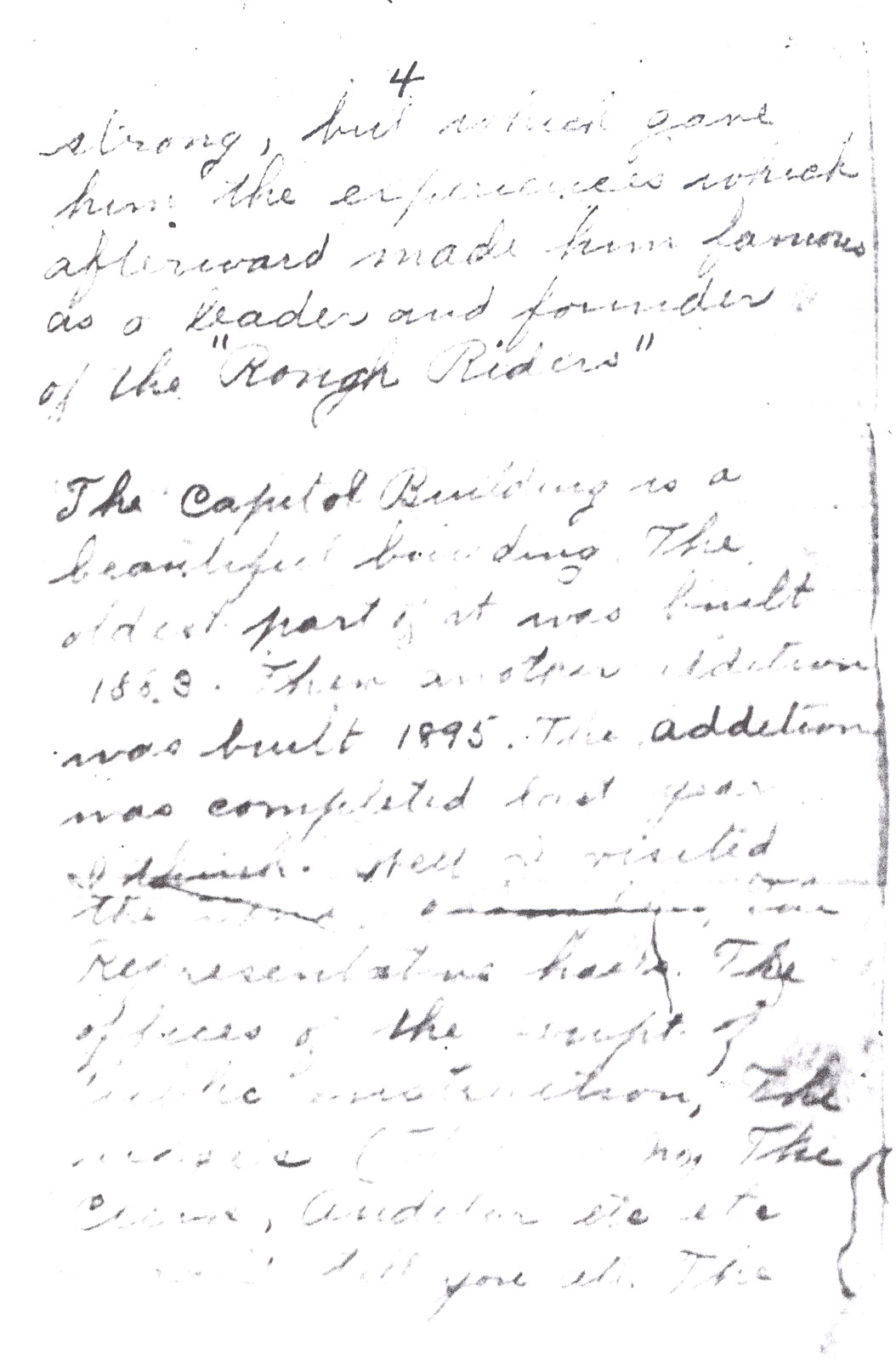

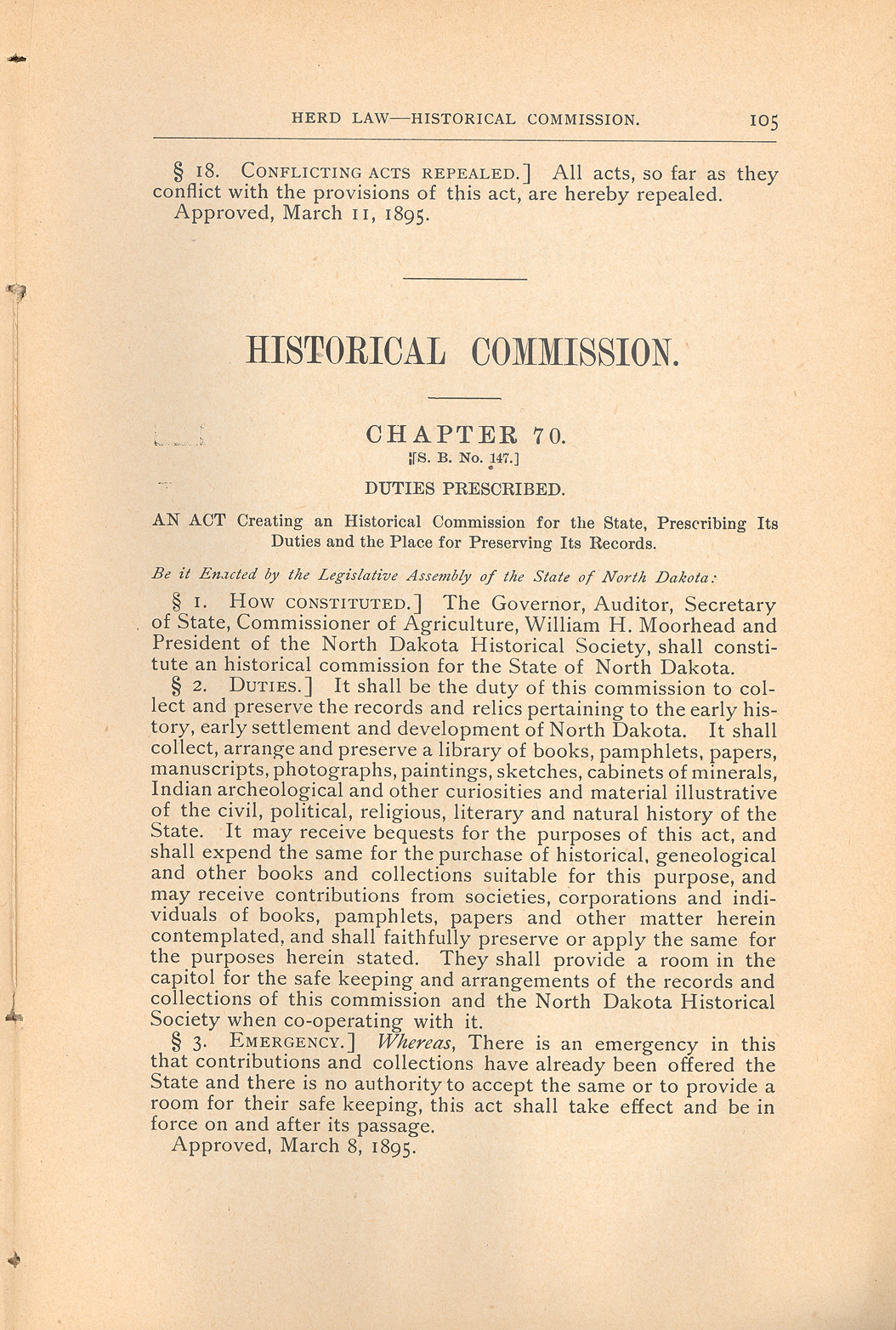

In 1895, the State Historical Society asked the legislature to pass a bill creating a historical commission. (See Document 3) This law allowed these pioneers of North Dakota history to put together a small museum and archives in the basement of the state capitol building. (See Image 7) This was not an ideal location for records and objects, but it was a start.

The State Historical Society used Lounsberry’s new publication, The Record, as its journal. In the first edition, Linda Slaughter presented her theory of history as an introduction to the State Historical Society. She wrote:

The experience of our ancestors is a topic of universal interest. The belief of our fathers is the groundwork of our faith. Our sense of justice perceives that the forerunners in the world’s work - those who have leveled obstacles and laid the foundation of worthy enterprises - are deserving of honor equally with those who in more auspicious times have reared the spire and painted the interior of the dome.

Slaughter was saying that North Dakota was not a great civilization such as ancient Rome, but that such an ordinary place had an important history, too. With this theoretical foundation, the young State Historical Society of North Dakota began to preserve the history of all the people who lived in North Dakota in order to allow future residents to understand the past.

Why is this important? Every culture has a means of preserving and passing on its historical knowledge. For the Lakotas in the 19th century, Winter Counts were the records of the past. For the pioneer generation of white settlers in North Dakota, the State Historical Society preserved the records and objects that defined the story of settlement and growth of the new state, including the histories of the American Indian tribes of the region.

Preserving history is about more than holding on to old stuff. It is about finding our cultural and personal roots in the past. We can draw on the inspiration of our ancestors’ lives. We can find answers to modern problems in the solutions people applied to their own problems in the past. We are never far from our past. Although technologies, economies, and lifestyles change, human nature and human relationships follow a continuous chain. Historians believe that we are all strengthened by the people who came before us.

Effie Clinkenbeard Visits the State Museum

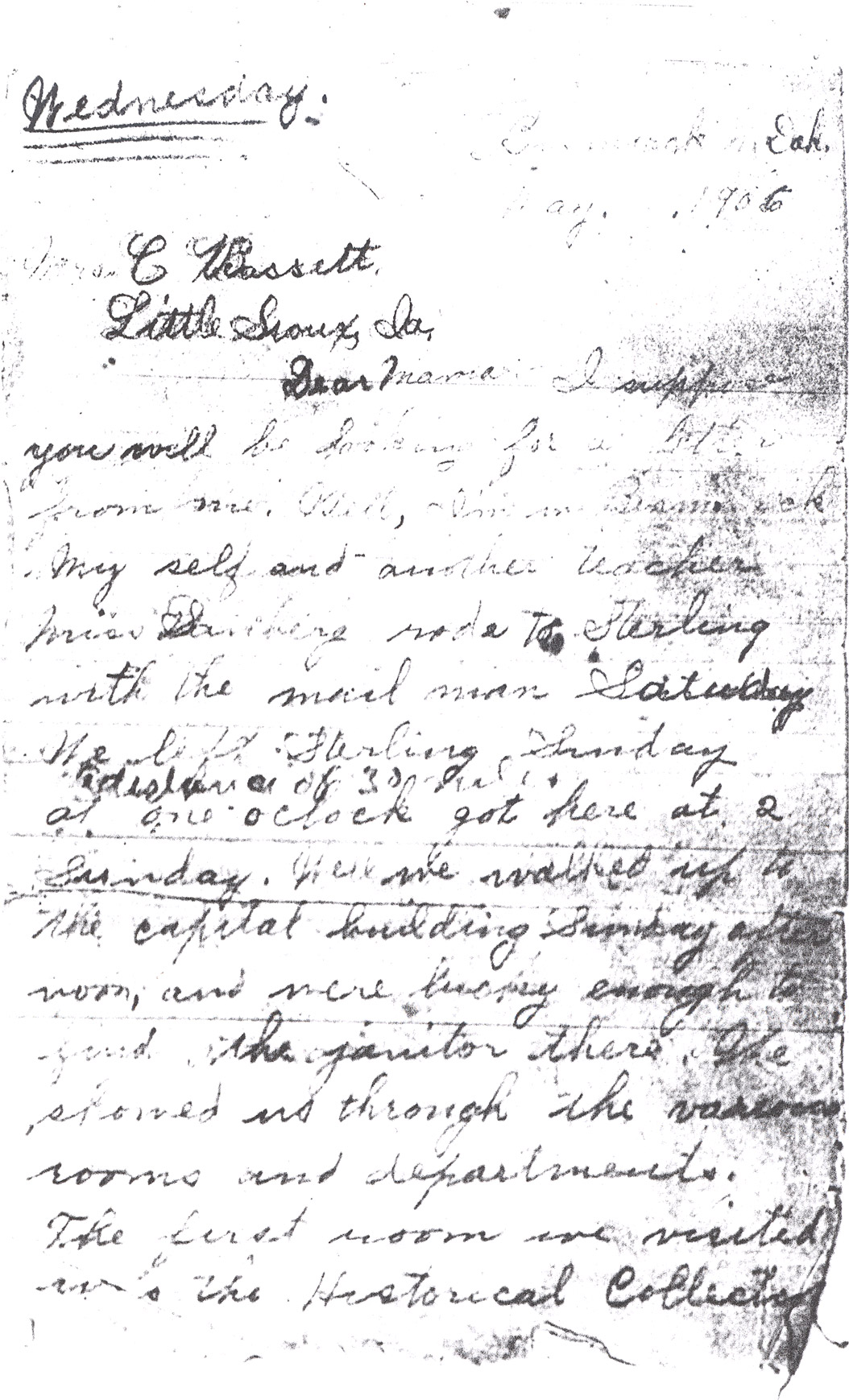

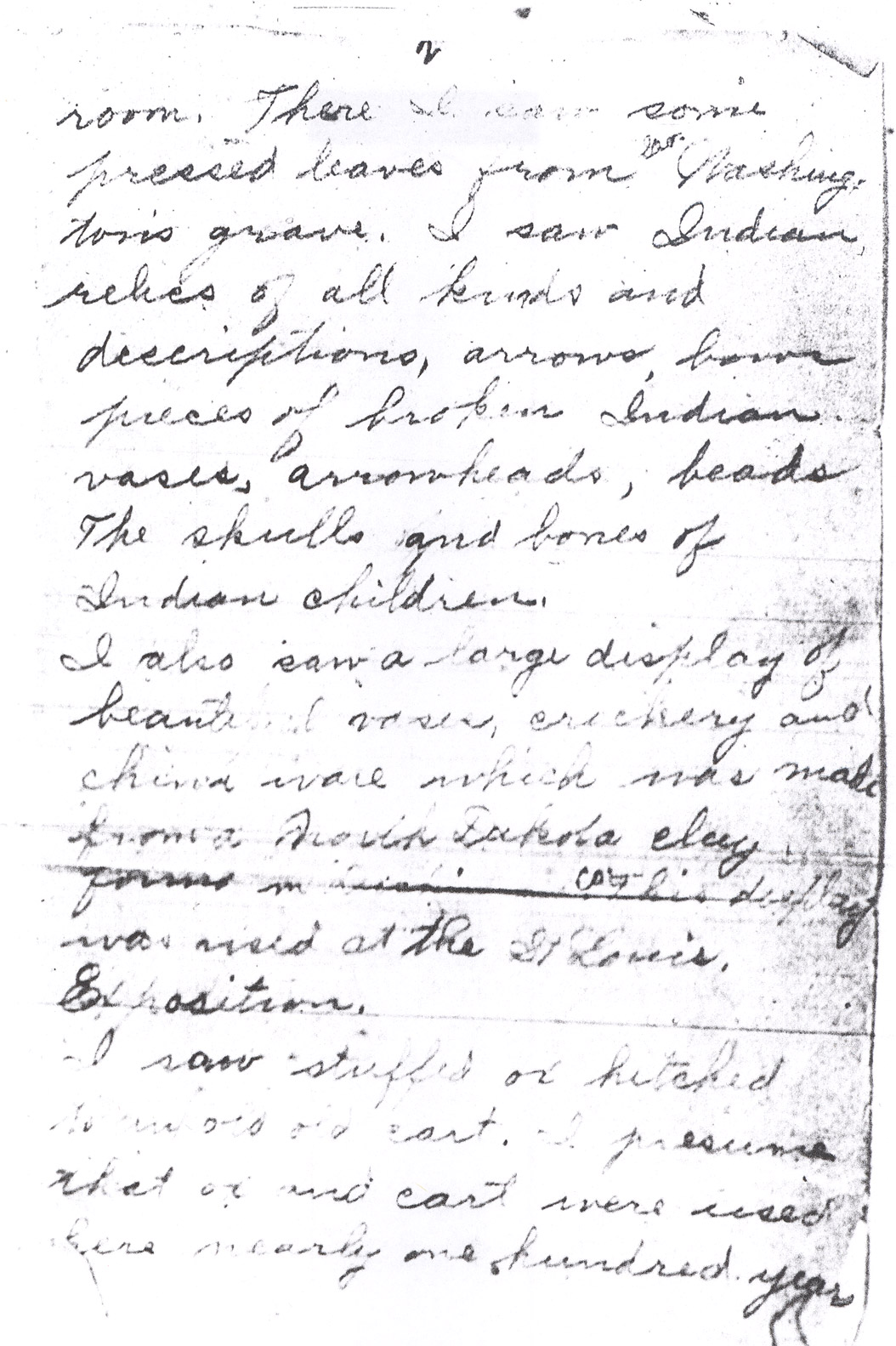

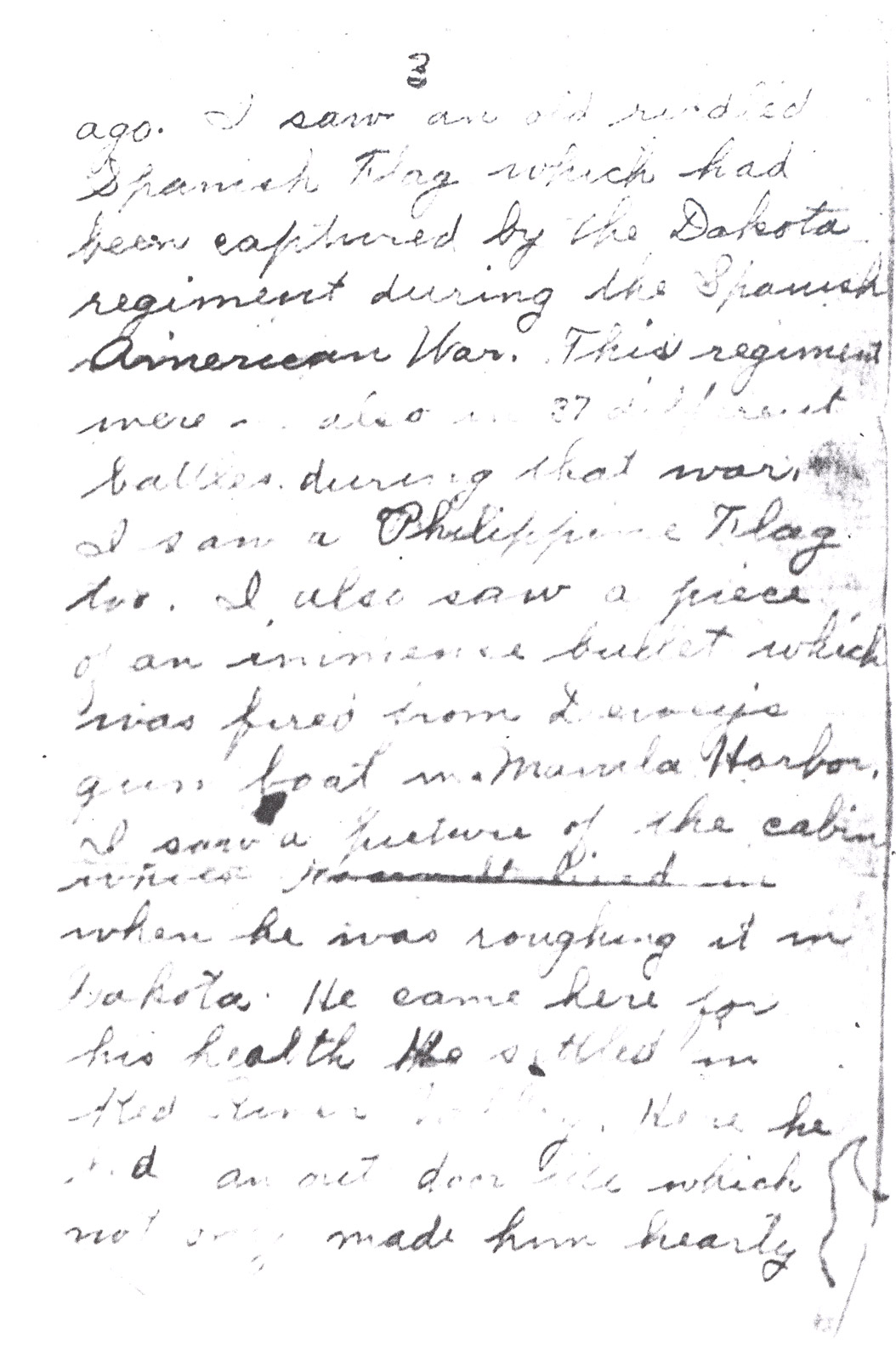

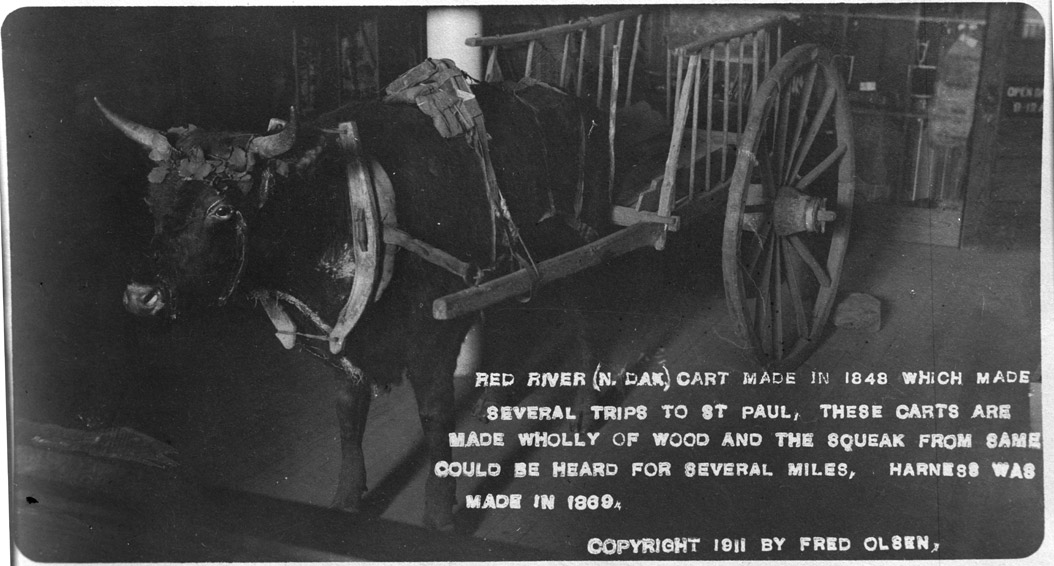

Effie Clinkenbeard and her friend, Miss Sanberg, came to Bismarck on a Sunday afternoon in May, 1906. Effie was so determined to see the state museum exhibits that she found a janitor in the capitol building to unlock the museum rooms for her. Effie enjoyed the exhibits and wrote a letter to her mother in Iowa full of enthusiasm about what she had seen. (See Document 4) The objects she saw included vases, an oxcart, and a Spanish flag captured in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War. She found all the objects fascinating.

Effie also wrote that there were “Indian relics of all kinds,” and the “skulls and bones of Indian children” in the museum displays. Effie did not seem to think these displays were unusual or shocking. She lived in a time when the archeological exploration had brought to light burial practices of ancient Egyptians. Mummified human remains and objects were taken from the pyramids (tombs) and taken to England and other European countries to be studied and put on display. It was all done in the name of science.

In the late nineteenth century, scientists and others often collected the remains and burial objects of American Indians. After studying these remains, scientists offered theories about how people lived in the past and what made humans different from one another. These scientists helped to create the idea that different races had different human qualities. Unfortunately, some of the scientists mistakenly concluded from their studies that Indians were inferior to European Americans. These theories about racial superiority were eventually found to be biased, unscientific, and inaccurate. However, the study of human remains advanced knowledge about how people lived in the past.

American Indians were very upset when the graves of their ancestors were disturbed and the remains were studied. Many American Indians hold a spiritual belief that the graves of their ancestors should never be disturbed. People of other cultures also believe that graves should never be disturbed.

In the 1970s, American Indians began a public campaign to make all Americans aware of the situation. American Indians of many different tribes demanded that the remains and grave goods of their ancestors be returned (repatriated) to their tribes for proper burial.

This demand generated a contentious debate. Some people said the scientific information that would be gained by studying the remains of American Indians was extremely valuable and would be lost if the remains were repatriated. Others said that every person is entitled to a proper burial in an undisturbed grave according to the traditions of his or her culture.

The debate led to significant change and North Dakota was the first state to act. In the late 1980s, in response to requests by American Indian residents of North Dakota, the State Historical Society of North Dakota released all of the human remains in its care to North Dakota Indian tribes for reburial.

In 1990, Congress passed a law requiring all federal institutions to release any American Indian remains in their collections to the appropriate tribe. This law, called the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was designed to protect the graves and sacred burial objects of American Indians. NAGPRA also recognizes the right of American Indian tribes to reclaim any of their sacred objects the museum may have acquired in the past. The State Historical Society of North Dakota, like most other museums, complies with the law and continuously works with tribal authorities when NAGPRA claims arise.

Why is this important? Effie Clinkenbeard did not see racism or tragedy when she viewed the remains of American Indians in the State Historical Society Museum in 1906. However, over the years ideas about race and human relationships have changed.

It is important to understand the long history of the collection of human remains and the process of repatriation. The time when remains were being collected was when the new sciences of anthropology and archaeology were becoming professions. It was a time of conflict between Anglo-Americans and many American Indian tribes. Anglo-Americans held many prejudices about American Indians that led to unfair treatment. It was also a time when state and federal governments did not often respect the interests of Indian tribes.

Today, there are no human remains in the collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota. State law (23-06-27) protects graves and objects within graves. State Historical Society archaeologists and museum curators consult with tribes concerning the protection and display of objects made by their ancestors. These objects are stored and displayed with care and respect. Curators at the museum believe that the objects can help foster understanding among people with different cultural backgrounds.