The third supporting question, “how did the war impact Americans at home?” helps students use sources to unwrap the context of the time and topic being examined. Complete the following task using the sources provided to build a context of the time period and topic being examined.

Formative Performance Task 3

Write a summary describing what the home front experience was like. How do we know? What else can you find? What was the impact on women, Jewish people, African-Americans, Hispanic/Latino people, and other groups?

Featured Sources 3

The sources featured in this section, A-M, are a combination of primary and secondary sources that help paint a picture of what life was like for Americans during World War II. What was the context under which each of these sources created? What can we learn about what life was like in America during this time period from these sources? What impact did the war have on the people living in North Dakota? How were Toyojiro Suzuki and Herman Stern reflective of issues that connected North Dakota to a global war effort?

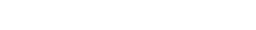

Internment Diary of Toyojiro Suzuki

Toyojiro Suzuki was interned as a Registered Alien in February 1942, just eight weeks after Japan bombed the US fleet at Pearl Harbor. This diary covers the six-month period of his internment at Fort Lincoln near Bismarck, North Dakota, and his separation from his family. This where United Tribes Technical College is located now, rather than historic Fort Lincoln south of Mandan, ND. Suzuki was born 16 April 1903 in Japan. He immigrated to the US in April 1920 to work in the fishing industry with his father (who immigrated before 1917). Though he obtained a Social Security number, he was not a naturalized US citizen. Though Toyojiro had married a US citizen, Takako Wada, the marriage did not change his citizenship status.

Suzuki along with other members of his family worked on a fishing ship called the Brittania Maru. At sea on 7 December 1941 when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, they were aware that their status in the United States would be questioned. In fact, their very presence in California had always been difficult. Californians had found Japanese, Chinese, and Korean immigrants to be productive workers in mines, farms, vineyards, and canneries, but did not welcome them as neighbors, landowners, or citizens. The United States did not offer immigrants of any Asian nation full citizenship status (and the rights associated with citizenship) until 1952 with the passage of the McCarran-Walter Immigration and Naturalization Act.

Immediately after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) and the FBI began to round up Japanese resident aliens and US citizens considered to be dangerous to the interests of the US, but it was several weeks before the US began to systematically detain all Japanese Americans, both citizens and resident aliens, and remove them from the West Coast. The first “assembly center” was at the Santa Anita horse racing track on the north side of Los Angeles. The Suzukis were sent there even before President Franklin Roosevelt had signed Executive Order 9066 on 19 February 1942 authorizing the removal of “any or all persons” from areas of military importance. Japanese Americans lost all their personal and real property as well as businesses during the process.

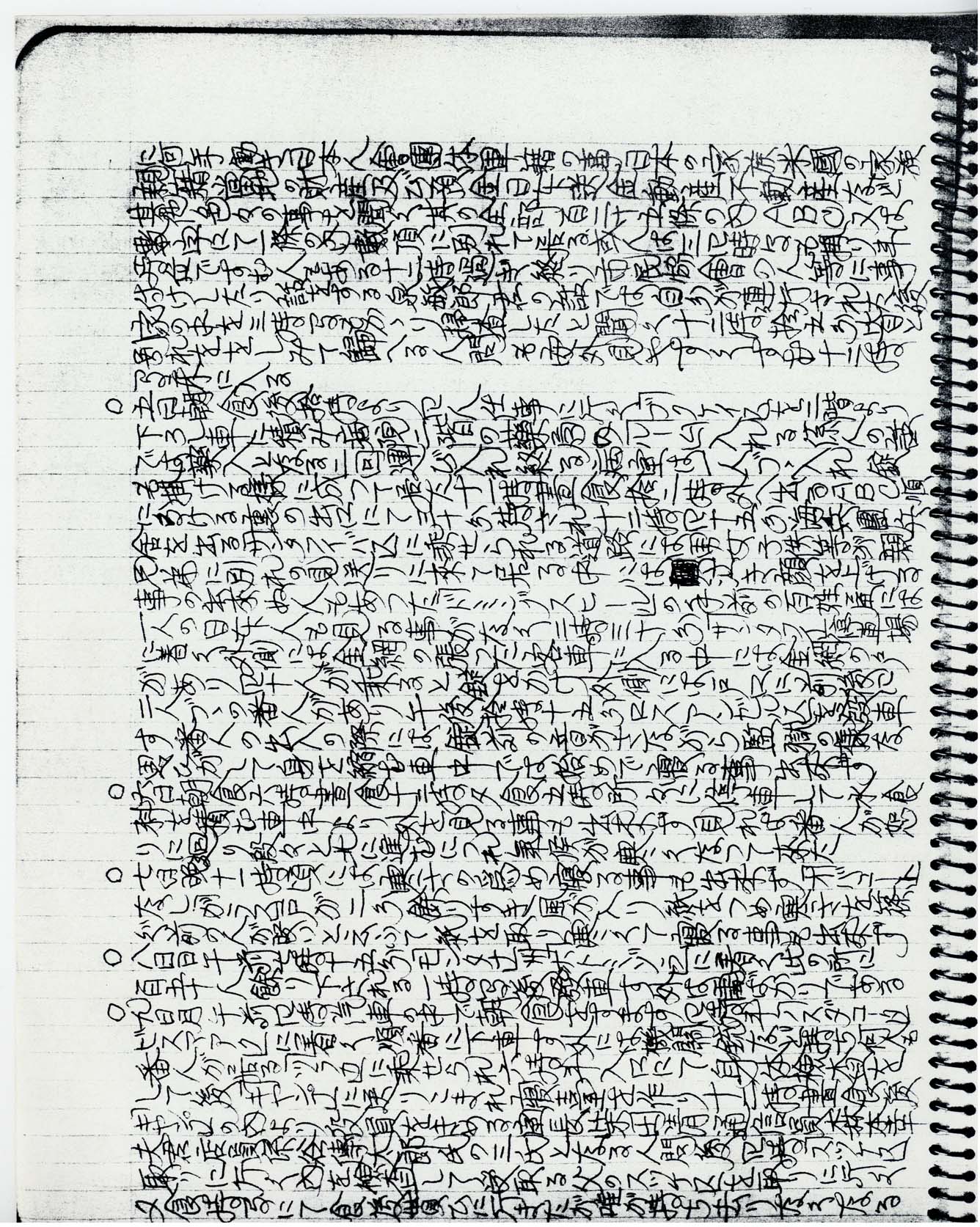

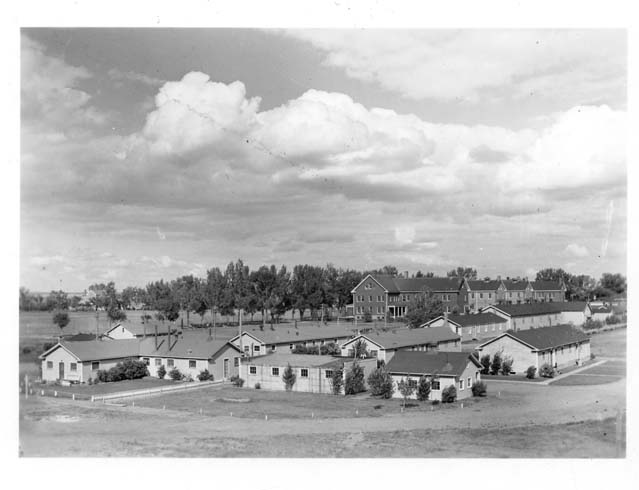

Fort Lincoln, south of Bismarck, became an internment camp in 1941. Before the US entered the war, German nationals were detained and sent to Fort Lincoln and other sites. Some were merchant seamen whose ships were in US harbors, while others were here seeking US citizenship. Nearly 4000 Japanese, German, and Italian internees passed through Fort Lincoln during its six years of operation as an internment camp. Many of the Japanese American internees (not including Toyojiro Suzuki) were men who had renounced their US citizenship and declared their intention to move to Japan after the war. All the Ft. Lincoln internees were men whose families were located (or interned) elsewhere. Toyojiro Suzuki was paroled from Fort Lincoln in August 1942, and with his father and others relocated to camps elsewhere. Suzuki was reunited with his family at Santa Anita racetrack. After the war, he remained in California where he died April 15, 1995. SHSND Mss 20988

Study the featured sources, A-L, and answer the following questions: How does Suzuki describe the day of his detention by Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents? Read a contemporary newspaper account of the evacuation of Japanese Americans. Compare Suzuki’s experience with the newspaper account. Why are they different? How did Suzuki, his fellows from the Brittania Maru, and the other internees organize themselves at Fort Lincoln? How did the arrival of other internees from other places impact their social order? On 30 April 1942, Suzuki says that the internees discuss the impact of world events on their situation. What might they have been thinking about the course of the war? What did the news of the Pacific front mean for them and their families? In May 1942 Suzuki was interrogated by Fort Lincoln officials. His interrogation was easy, but Mr. Sumi was savagely beaten. Why were they treated differently? How did the internees respond to Mr. Sumi’s beating? Was their solution satisfactory? Did it diminish the anger that swept through the camp upon hearing of the beating? Many of the internees at Fort Lincoln were “renunciators” – men who had declared that they would relinquish (or renounce) US citizenship and move to Japan as soon as they could leave. Was Suzuki a renunciator? Suzuki's diary gives us a close-up view of the US preparing for war. Was the nation ready in 1942 to fight an international war on two fronts? Support your answer with evidence from the diary.

| Source A |

People who Suzuki Wrote About Takako (née Wada) Suzuki: Toyojiro’s wife. She was born in California in 1918, and married Toyojiro in the late 1930s. Takako was a native-born citizen of the United States who completed three years of high school, was fluent in English, and could speak Japanese. She worked in a cannery operation before her internment. Chiyo Suzuki: The daughter of Toyojiro and Takako Suzuki, born in 1941. Takei Suzuki: Toyojiro’s father, born in 1880. He immigrated to the US from Japan in 1917, before World War I, and worked in the fishing industry. Yone Suzuki: Toyojiro’s mother. Toyojiro wrote to his mother at an address in Japan during his internment at Fort Lincoln suggesting that Yone Suzuki never immigrated. Mr. Wada: A fisherman, and apparently, Toyojiro’s father-in-law. Sidney Hillman: A US labor leader who worked for the Office of Production Management from 1940 to 1942. Toyohiko Kagawa (1888–1960): A Christian pacifist and labor activist of Japan. He dedicated his life to the poor and established hospitals, schools, and churches while campaigning for woman suffrage and international peace. He was often at odds with the Japanese government and was arrested many times. However, he was instrumental in establishing a transition government after World War II. |

| Source B |

Vocabulary Allied Powers: The major Allied Powers during World War II were the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union (Russia). Axis Powers: The major Axis Powers during World War II were Germany, Italy, and Japan. Banzai: The use of this word has changed greatly over the centuries. Traditionally, it was used to mean something like “hurrah” or “long life.” When crowds of Japanese shouted banzai three times with their arms stretched above their heads it had the effect of applause. The term was also associated with paying respect to the emperor. During World War II, the word came to be associated with military attacks. Bataan: On 9 April 1942. US officers, soldiers, and Filipino soldiers surrendered at Bataan. They were forced to march for days with little food and water to their prison. The death rate among the prisoners was very high. Hana fuda: An ancient Japanese card game. JACL: Japanese American Citizens League was founded in 1929. During the period of internment (coinciding with World War II), the JACL supported lawsuits against the federal government and provided internees with various means of support Nisei: Term for second generation Japanese Americans. The children of this generation were born in a country other than Japan to parents who immigrated from Japan. Many of the interpreters were Nisei. Normandie: A French Line passenger ship which when launched in 1932 was the largest and fastest ship in the world. She was converted to a troop ship in 1942 but sank after a fire while in port at New York. |

| Source C |

http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/3216 |

| Source D |

Suzuki’s Diary

The forty-two names listed at the beginning of my diary—starting with Ryokichi Hashimoto and ending with Yaoichi Ichiki——are the names of my fellow fishermen and my fellow countrymen with whom I Journeyed North to a barren and God-forsaken area of ice and snow near the Canadian border. Here——in the isolated backcountry of North Dakota, we were forcibly incarcerated. Our lengthy confinement within an encirclement of armed guards was for political reasons that were far beyond the control of the men of the fishing fleet in Fish Harbor--- --.TERMINAL ISIAND. T. Suzuki |

| Source E |

Fort Lincoln, Bismarck, N.D. SHSND 20998. |

| Source F |

The main gate at Fort Lincoln, Bismarck, N.D. SHSND 20998. |

| Source G |

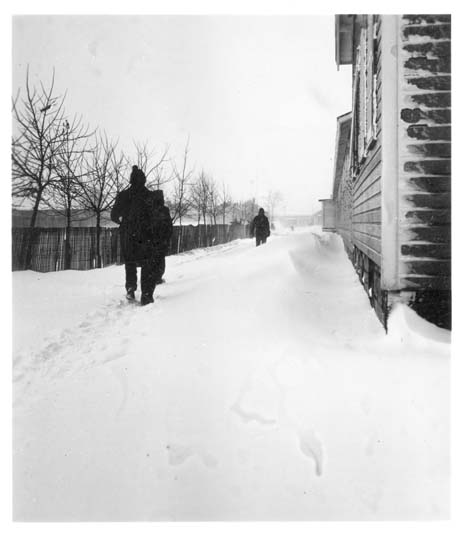

Records do not indicate whether these photographs of snow piling up and blowing around the barracks were taken by Toyojiro Suzuki, but he does mention in his diary that he went out one day to take photographs. He was both fascinated and horrified by the snow and cold of the northern plains, a climate that he had not experienced before his internment. SHSND 20998. |

| Source H |

SHSND 20998. |

| Source I |

SHSND 20998. |

| Source J |

SHSND 20998. |

| Source K |

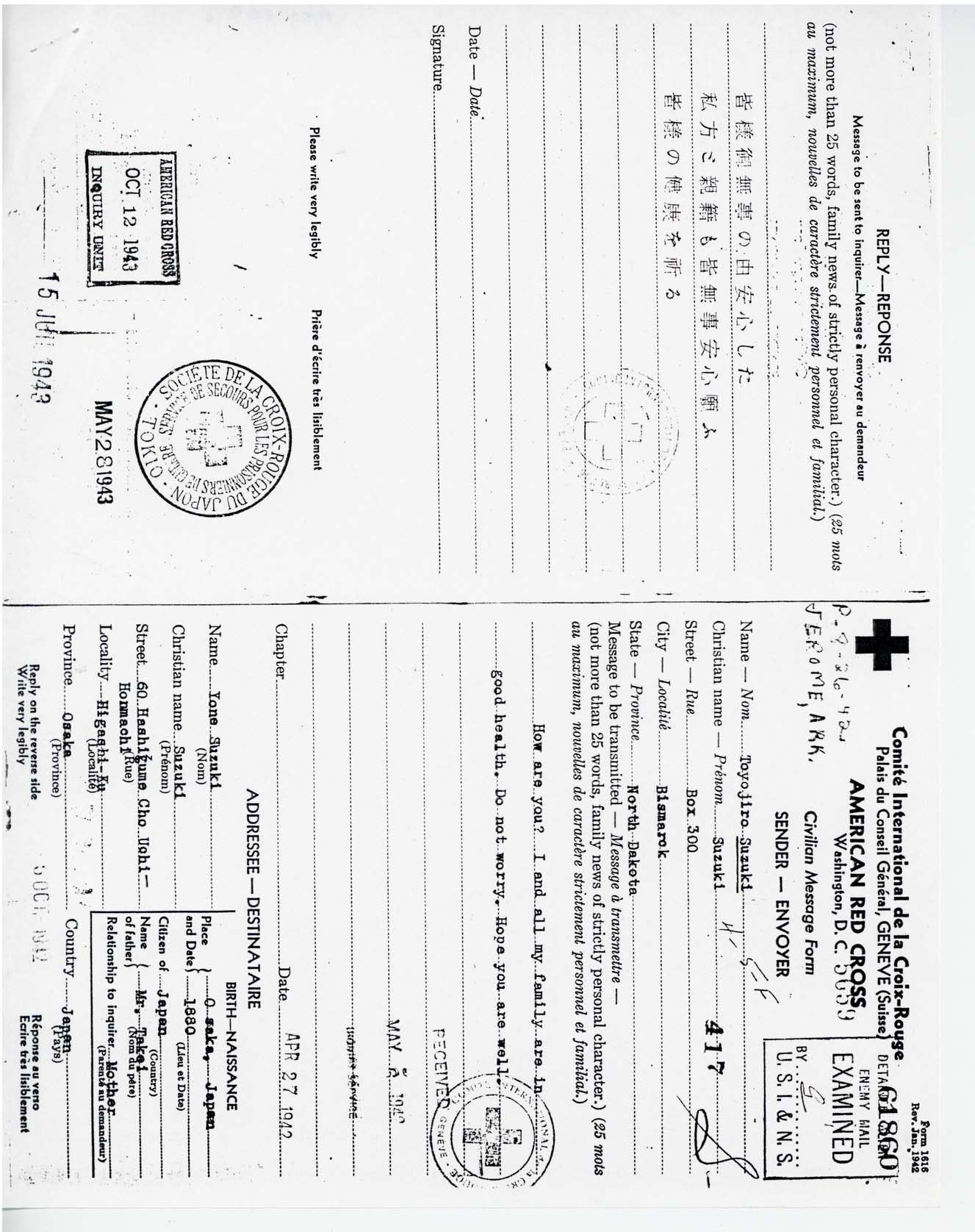

The Red Cross sent information on Suzuki to his mother in Japan after he completed this form. SHSND 20998. |

| Source L |

This wool pennant, a typical tourist souvenir of Bismarck, is among the papers of Toyojiro Suzuki. SHSND 20998. http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/3213 |

The Mission of Herman Stern

| Source M |

The Mission of Herman Stern is the true story of how one North Dakotan made a difference in the lives of over 125 people by rescuing them from Nazi Germany. Watch the film and access the teacher guide here by scrolling down the page and clicking on his name. |