The second supporting question, “how did the war impact Americans abroad?” helps students use sources to unwrap the context of the time and topic being examined. World War I broke out in Europe in 1914. It was called Initially called the Great War, and it would not be until after World War II that it would become known as World War I. The United States kept a wary eye on the war, while asserting its right as a neutral nation to engage in commerce with all belligerents. The US did not see itself as an international power, and there were many people in the US who believed that taking part in the war would be detrimental to our international status as well as our economy. North Dakota held a strongly isolationist view of the conflict. However, after many ships sailing under a US flag were torpedoed by German U-boats (submarines), and diplomatic efforts to protect US shipping failed, the US finally declared war against Germany and its allies (Austria-Hungary and Turkey) in April 1917 and joined forces with Britain and France to fight the Germans. The war had continued for two and one-half years, mostly on French and Belgian territory. Trench warfare was the typical means of engagement. Each side dug long trenches in which the soldiers lived and fought until they were able to gain a bit of ground. The trenches were damp and cold, and disease was as significant as weapons in raising the huge casualty toll.

US troops and strategy brought renewed energy to the Allies’ efforts. The war finally concluded with an armistice (ceasefire) on November 11, 1918. By late spring of 1919, most US troops had returned home. The war was a turning point in many ways. The US would not be able to maintain neutrality in a world-wide conflict and its military power would continue to increase during the twentieth century. New technologies, such as automobiles, airplanes, telephones, and radios developed rapidly and became more practical. North Dakotans would benefit from new technology – especially telephones and radios – but would also find their economy closely linked to international financial conditions.

For the soldiers who had fought in Europe, life would never be the same. Some came home suffering from “shell shock,” which today might possibly be diagnosed as PTSD. Others suffered from alcoholism. Many men and women who had been to Europe did not want to return to small town or farm living. Urban life, higher education, and jobs with major corporations began to have more appeal. By 1920, the US officially had more people living in cities and towns of more than 2000 people, than people living in the countryside. Though this trend had been underway throughout the nineteenth century, World War I, and the changes it wrought in individuals and the US economy, was one of the contributing factors in the demographic shift from rural to urban settings.

Many soldiers who fought in Europe in 1917 and 1918 were amazed by the beauty of European villages and cities but stunned by the awful destruction of the war which was one of the deadliest of the twentieth century. They took photographs and brought home souvenirs that helped their families understand their experience and would help them remember that time and place for the rest of their lives. Complete the following task using the sources provided to build a context of the time period and topic being examined.

Formative Performance Task 2

Study featured sources A-C closely for evidence of what life was like for soldiers and other American citizens living abroad during the war. Write a summary that answers the following questions: What type of source are these (letters, photos, maps, diaries, etc.)? What kind of information do they contain? Who created these sources? Who was the intended audience for each source? Why were these sources created? When were the sources created? What do the sources tell us about what the war was like? How do we know? What else can you find?

Featured Sources 2

The featured sources A-C in this section illustrate the impact that war had on individual North Dakotans. Their experiences shaped their adult lives. Consider the role of letters, diaries, notes, and photographs in recording history. The person who writes the letters or takes the photographs has some intent in mind. The person who later views these documents sees something a little different. Consider making a photo essay of your town, your family, or your school. Type captions for each picture. What do you consider important? What will people in the future be looking for when they view your pictures and read your captions? Will they understand what you want them to know? Do some research on American women in World War I. How did they support the war effort? Were there any World War I women volunteers from your town or county? You might find the answers to these questions by reading your town or county history, looking at newspapers from the years of the Great War. Ask a local historian or librarian if they know of any local documents, memoirs, or artifacts relating to women’s service in World War I.

| Source A |

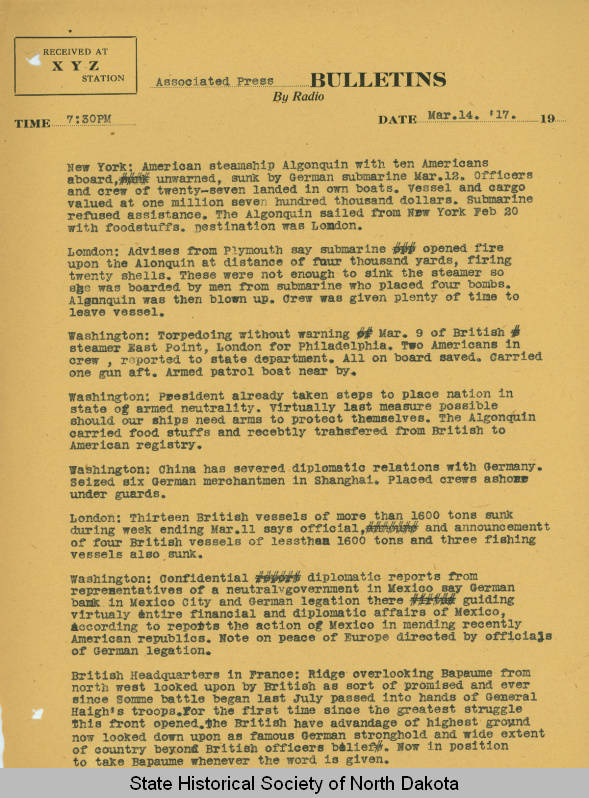

News Reports of the Great War, 1917

SHSND Mss 20695 http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/3044 At the age of 15, Van Meter Cousins of Carrington had an important job. He received Associated Press (AP) news reports, via the Fargo Forum and the North Dakota Agricultural College (now NDSU) wireless transmission on his crystal set receiver. He typed up the press reports and posted them in downtown Carrington so all residents could read the up-to-date news of the status of the war in Europe and of the United States' diplomatic relations with Germany and Mexico. Voice broadcasting on radio waves was a new technology in 1917 and was under the control of the US Navy until after the war. Radio broadcasting of regular news and entertainment programs did not happen until the 1920s. A crystal set did not require batteries or external power. The antenna picked up radio waves and coils, placed at the exact spacing for receiving, translated the radio waves into words that could be heard through earphones. Van Meter Cousins' interest in radio continued beyond his teen years. By 1930, he had moved to New Jersey where he had a job as an electrical engineer. The news that Cousins reported is interesting historically because it traces incidents of German submarines (another new technology) attacking merchant and passenger vessels on the high seas. This was one of the issues that drew the US into the war. In addition, we can read about the internment of German seamen (a policy applied again in World War II), the progress of the war in Europe, the reluctance of North Dakota and other states to enter the war, and the price of wheat which, during the war, reached unheard of prices near two dollars per bushel. This selection of eight of Cousins' fifty-six postings housed in the State Historical Society archives ends with President Wilson signing the Declaration of War against Germany. |

| Source B |

The Great War, A Photo Essay Study all the photographs taken by Lt. Huston. Use the Visual Thinking Skill (VTS) strategy to facilitate a discuss of each photograph individually. Allow the class to study the image in silence for a minute or two, and then facilitate a discussion about what they think is going on in the photo. How do they know? What else can they find? |

| Source C |

Leila Halverson Goes to War When the war was devastating Europe, Jane Delano, national head of Red Cross nursing, recruited Halverson from her school nurse position to serve civilian populations in France. Later, when the US entered the war, Halverson also worked in military hospitals caring for French, English, and American wounded men. After the war, Halverson went on to serve as a nurse in the Middle East and Poland. Later in life, she taught nursing and held the positions of treasurer and secretary of the State Board of Nurse Examiners in Minnesota. Leila Halverson went to war with the Red Cross. In addition to the 8,000 Red Cross nurses, more than 30,000 women served in some branch of the military service as nurses, occupational therapists, ambulance drivers, and as telephone operators with the Signal Corps. Women were not fully militarized, meaning they did not have rank and were dismissed without military benefits after the war. While the Red Cross provided women nurses with a career, the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps did not. Leila Halverson was typical of many professional women of her time. From the late nineteenth century until the 1930s, the marriage rate for women declined while the number of women seeking a college education and a professional career increased. Leila Halverson fit that profile because she was not married and set out to excel in one of the few professions open to women at the time. In doing so, she was able to make a living, travel widely, and have a satisfying career. Leila Halverson wrote a memoir of World War I after she retired from her busy and varied career. Included here are two excerpts from the memoir. In the first section (pages 1, 2, 3), she tells of living with the constant bombardment of Paris, learning to work in surgery (a huge change from being a school nurse), and her pride in being a North Dakota nurse. The second excerpt (page 4) tells of the armistice and the joy the French felt with the end of the war after four difficult years. Halverson uses some terms that may be unfamiliar to the modern reader. Blessee is the French word for wounded soldiers. Dakin solution was an antiseptic used to clean wounds; there were no antibiotics. Airplanes (another new technology of war) carried many of the bombs that were dropped on Paris, but the Germans also used cannons. It is doubtful that the cannon fire Halverson heard in Paris in 1918 was actually from one of the four guns called Big Bertha; these gigantic cannons had been removed from service before this date. A pension is another term for a small apartment. SHSND Mss 20208

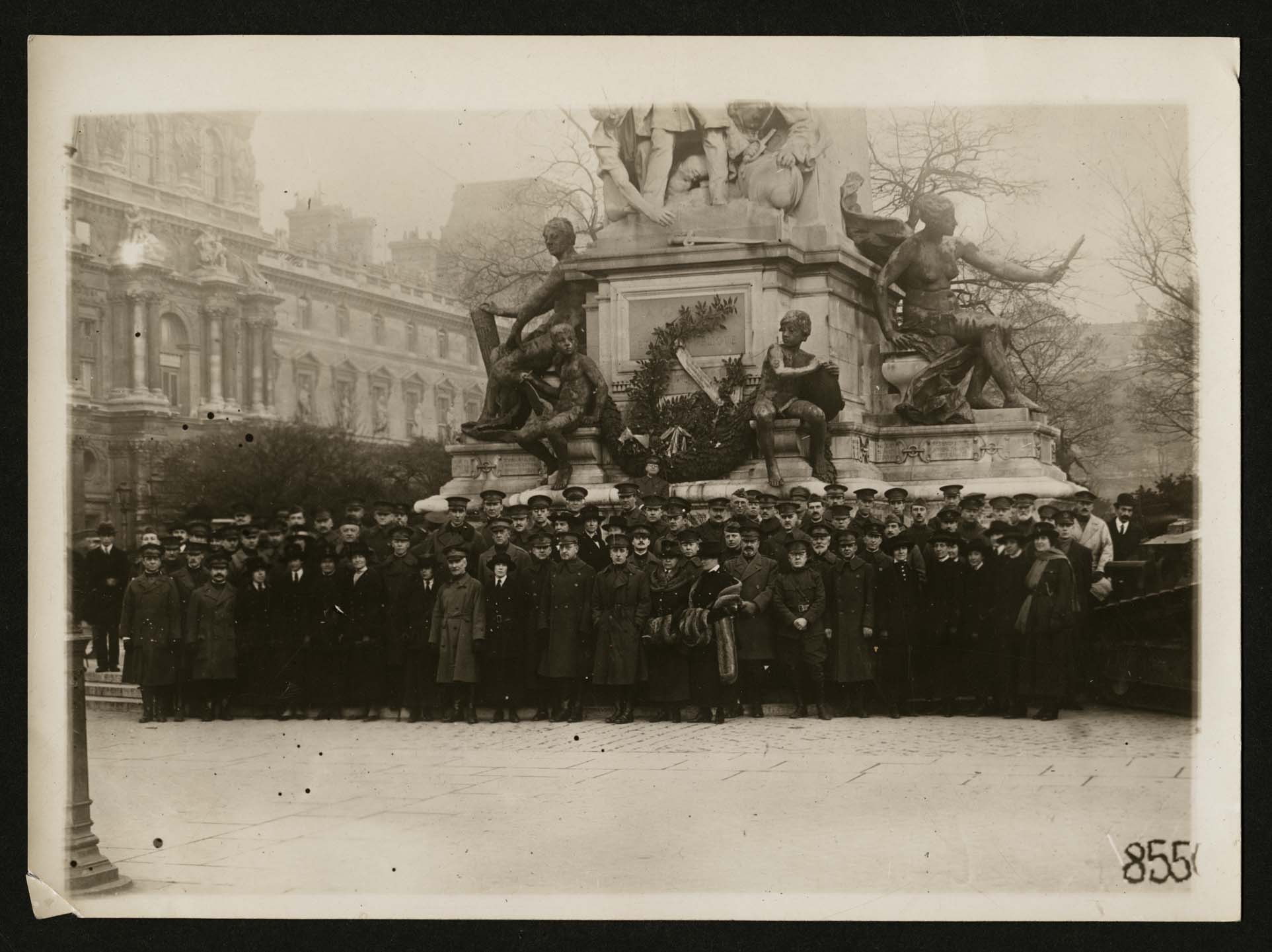

The Red Cross sent doctors and nurses to France during and after the war to care for civilians. In this photo, Dr. Cora Allen tends to French children. A large group of Red Cross nurses, doctors, and support staff gathers for a portrait in Paris at the statue of Gambetta. Like Leila Halverson, most Red Cross workers tried to absorb the cultural experience of their time in France as well as caring for the poor and wounded soldiers. SHSND A4527. Excerpts from a manuscript detailing Leila Halverson's time as a nurse in France during World War I.  |