The third supporting question, “What impact did the fur trade have on new generations of people living on the northern Great Plains during this period?” helps students use sources to unwrap the context of the time and topic being examined. Shortly after the Corps of Discovery returned to St. Louis in 1806, leaders of the fur trade business began making plans to expand their trade farther up the Missouri River. Within a few years, fur trade posts were established to facilitate the exchange of furs harvested by Indians and fur trappers for trade goods which might include cloth, metal goods such as cooking kettles, or knives, guns, and traps. The men who managed these trading posts for the companies headquartered at St. Louis or New York were often called clerks.

One of the largest and most successful of the fur companies was the American Fur Company which built Fort Union on the upper Missouri River in 1828. The American Fur Company stayed in business until the 1860s though the beaver hide trade which fueled much of the St. Louis economy for several decades declined in the late 1830s when fashionable men gave up their beaver felt hats for silk hats. Although small fur hides such as muskrat and mink and continued to be significant mechanisms of cultural exchange for many more years, the greatest export shifted to bison hides. These larger and heavier hides were baled and shipped downstream on shallow-draft steamboats designed for the Missouri River. The labor needed to support this growing economic engine became a source of employment for adventurous young men. The men who went to work for one of the many fur companies that operated west of St. Louis often married women of the Indian tribes with whom they lived and traded. These marriages were said to be made “in the fashion of the country,” meaning that the men did not take Christian marriage vows but made a marriage in a manner that was acceptable to the woman’s family. Many white men in the fur trade did not consider these marriages immoral or temporary and remained devoted to their wives and children. Other men, however, married Native American women for help in their work and for companionship, but did not think of the relationship as permanent. The children of these marriages grew up in two cultures. Some were sent by their fathers to schools in eastern states where they learned English, Christian religious concepts, and a trade.

The men of the fur trade who brought capitalism and other cultural values to the Great Plains also paved the way for European and American families. They helped establish the trade centers and towns, aided immigrant travel, and worked for the Army as Native American tribes were forced onto reservations. The men of the fur trade brought with them the seeds of change that grew into towns and farms. Some fur traders retreated farther west, others returned to their families and homes in Missouri or farther east, while still others remained on the northern plains where they were able to use their knowledge of Native American cultures, the landscape, and business to their advantage. Here is the story of one of those men, Fred Gerard, and his efforts to find a new place for himself in Dakota Territory and educate his daughters to become “proper” ladies. Complete the following task using the sources provided to build a context of the time period and topic being examined.

Formative Performance Task 3

Write a summary describing how the fur trade impacted the children of Native American women and European and American men. Evaluate the role of fur traders such as Fred Gerard in the social and cultural transitions on the northern plains. Compare it to other transitional (change) forces such as those brought by the Army, the railroad, and territorial government. Draw some conclusions about Gerard as a businessman, father, husband, and agent of change. Consider the implications of intercultural marriage. How does a couple decide which cultural traditions will be passed on to their children? How should families and friends adapt to the situation? Should one person give up their language, faith, and other traditions? How do people learn about and maintain multiple traditions?

Featured Sources 3

Read featured sources A-H. In a group or as a class, answer the following questions: What type of sources are they (letters, photos, maps, diaries, etc.)? What kind of information do they contain? Who created each of these sources? Who was the intended audience for each source? Why were these sources created? When were the sources created? How do we know? What else can you find?

Fred Gerard

Frederic Francis Gerard was born Nov 14, 1829 near St. Louis, Missouri to French-Canadian parents. He benefited from an education at Xavier College where he studied medicine. At the age of 19, he left home and traveled up the Missouri River to Fort Pierre where he was hired as a clerk for the American Fur Company. The next spring, he traveled farther upriver to Fort Clark, which had been built in 1831 between Hidatsa and Arikara villages and adjacent to the Mandan village of Mih-tutta-hang-kush. Here, Gerard often spent winters with the Arikara and learned to speak their language. In 1855, the company transferred him to the post near Fort Berthold where he remained until 1869.

While managing the Fort Berthold posts, Gerard took an Arikara woman as his companion. Her name was Helena Catherine and together they had three daughters named Josephine (1860), Carrie (1862), and Virginia (1864). These daughters were baptized by Father Pierre-Jean De Smet. In 1874 the three girls were sent east to a Catholic boarding school for their education. As young women, Josie and Virginia became sisters of the Benedictine order and served as nuns at a convent in St. Joseph, Minnesota.

Gerard had many encounters, both hostile and friendly, with the Native Americans he met at his trading post. As the clerk of an important trading post near the Missouri River, he also met non-Native people who were moving onto the northern plains and passing through on their way farther west, including the ill-fated group of miners returning to St. Louis with a boat full of gold dust. (See the Conflict on the Prairie inquiry) [include link here]. Smallpox had devastated the Mandan and other tribes in 1837 and recurred frequently in subsequent years. In 1866, Gerard convinced the Arikara leaders to allow him to vaccinate the children against smallpox which protected them during the next outbreak.

After 1869, when the American Fur Company sold its stock to another trading outfit, Gerard became an independent trader with stores at forts Berthold and Stevenson. He set up a store near Fort Buford, but in 1871, but military regulations soon forced him out. By now, his companion was Katie or Katherine Rider, of the Blackfeet nation with whom he had a son, Frederic. He intended to establish trade with the Blackfeet along the Canadian border, but his wagons carrying goods to Fort Benton were attacked, and he lost all his supplies. He gave up the fur trade and tried to establish a ranch across the river from Bismarck. He also worked as an interpreter because he could speak Lakota, Arikara, and Chippewa as well as French and English. When it was discovered that his land claim was on land that actually belonged to the Northern Pacific Railroad, the railroad exchanged it for other land in honor of his service. They gave him 40 acres between the Missouri and Heart Rivers.

By 1876, Gerard was working as an interpreter at Fort Abraham Lincoln, a post he would hold until 1883. He traveled with the Seventh Cavalry to the Little Big Horn River in Montana where he was assigned to General Reno’s command and narrowly escaped death in battle. In 1879, at the age of 50, he married Ella Waddell of Kansas City. Ella Waddell was a young woman, and a member of a prominent family. With Ella, Gerard had four more children, Frederic (1878), Birdie (1880), Charles (1888), and Florence (1893). He remained an affectionate father to his three oldest daughters and Ella’s children, but he apparently left Katie’s son, Fred, to be raised by others. Carrie lived with Gerard’s third family until she reached adulthood.

During the 1880s, Gerard opened a store in the new village of Mandan, and he served on the Morton County commission. He also operated a ferry across the Heart River. In 1890, Gerard and his family moved to St. Paul, Minnesota where he worked in advertising for Pillsbury Baking Company. The last months of his life were spent in the care of the Benedictine nuns at St. Cloud where his two daughters lived and worked. He died January 30, 1913.

Frederic Gerard experienced, and to some extent fostered, the great economic, social, and political transitions of the northern plains. His families remind us that the transition from unorganized territory to statehood, from a region dominated by several different Native American tribes to one dominated by the culture and government of the United States, came at a very high cost for some individuals. Source: SHSND MSS 20147.

Of Fred Gerard’s four letters to his oldest daughters, the first three letters were written to all three daughters who lived and studied in a Catholic boarding school after 1874. Though Gerard stayed in touch with their mother, he did not continue to live with her after about 1871. The fourth letter was written only to Virginia at the time she took her vows as a nun. Virginia was 19 at the time and the youngest of his three daughters by Helena. Virginia became known as Sister Anasta when she took her vows. Josephine also became a Benedictine. Historians have viewed these letters as important for their insight into the way men prepared for the expedition that led to the Battle of the Little Big Horn and their experience there. However, these letters are also rich records of the social and cultural transition the daughters of the fur trade had to negotiate. Gerard reveals his hopes and expectations for his young daughters as well as his efforts to prepare them to live in a world very different from that of their mother and other Arikara relatives. There are no known childhood pictures of Gerard’s daughters by Helena Catherine or his son by Katharine.

| Source A |

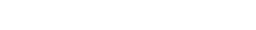

Frederic Francis Gerard

Fred Gerard worked at Fort Lincoln as a scout and interpreter for several years. SHSND: A3778. |

| Source B |

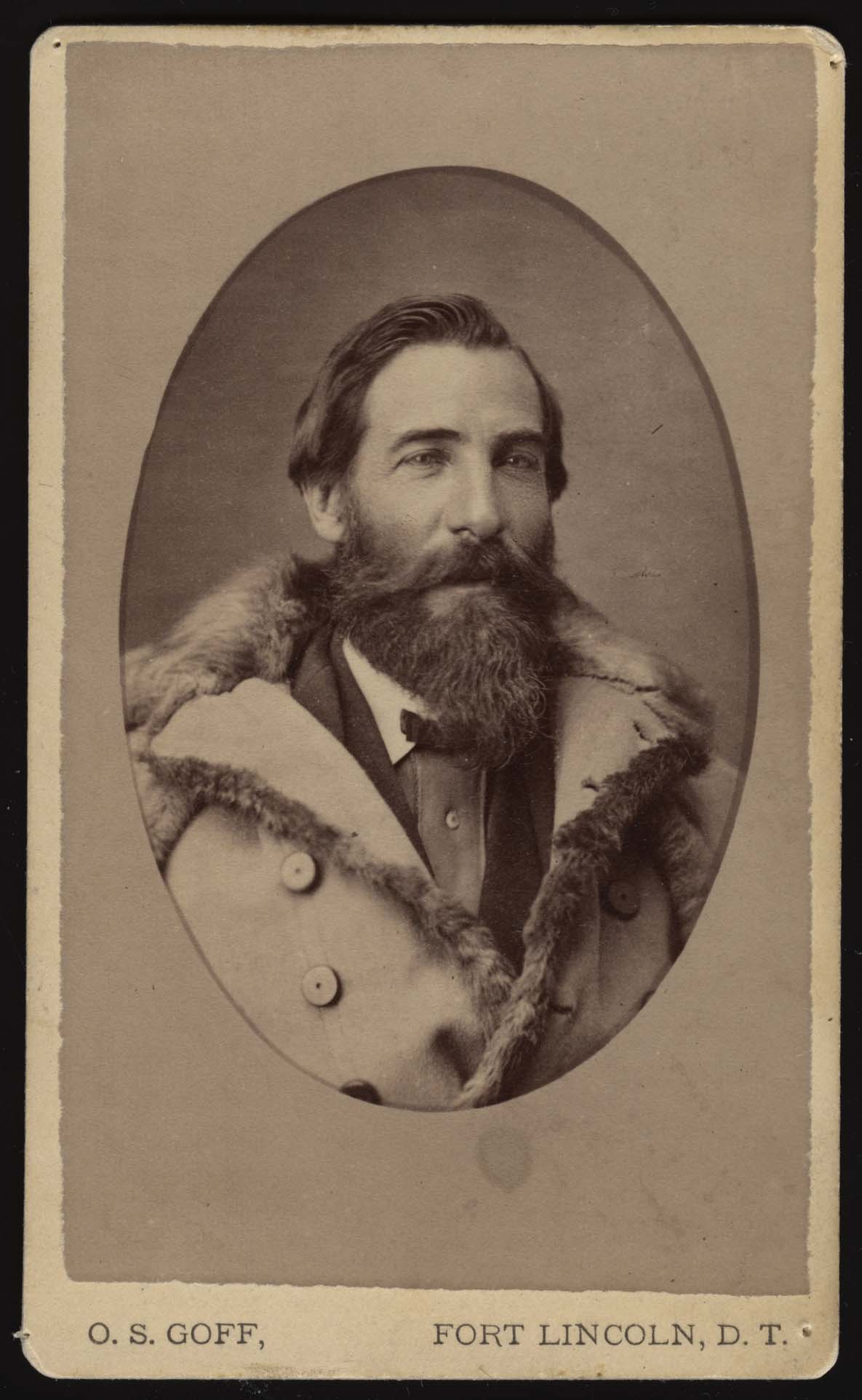

Fred Gerard, shown here in a Saint Louis photography studio, was a fur trader and a successful businessman. SHSND: A3277. |

| Source C |

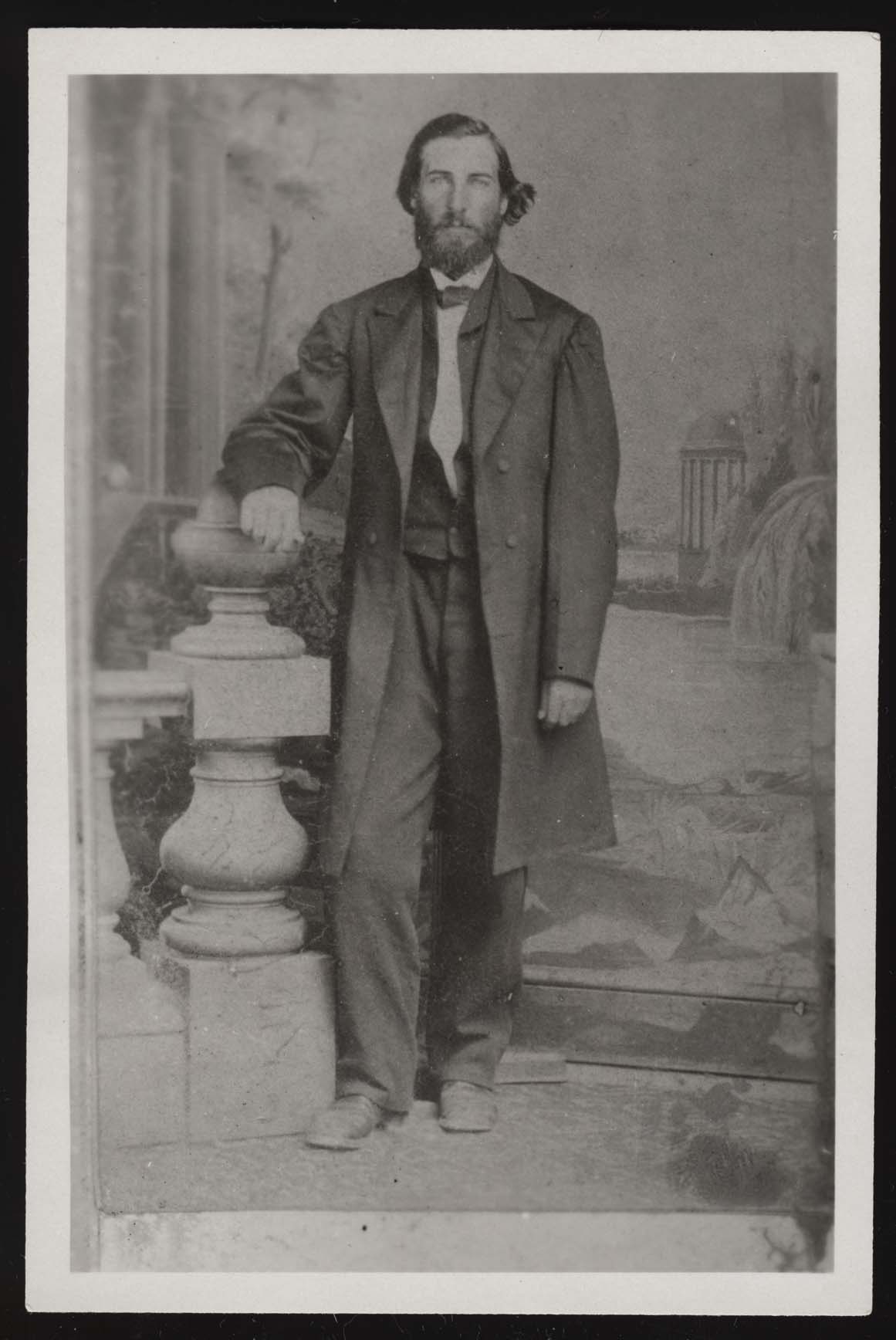

Ella Scarbaugh Waddell was born in Kansas City. She married Fred Gerard in 1879 and was the mother of four of his eight children: Frederic, Birdie, Charles, and Florence. SHSND B782.2. |

| Source D |

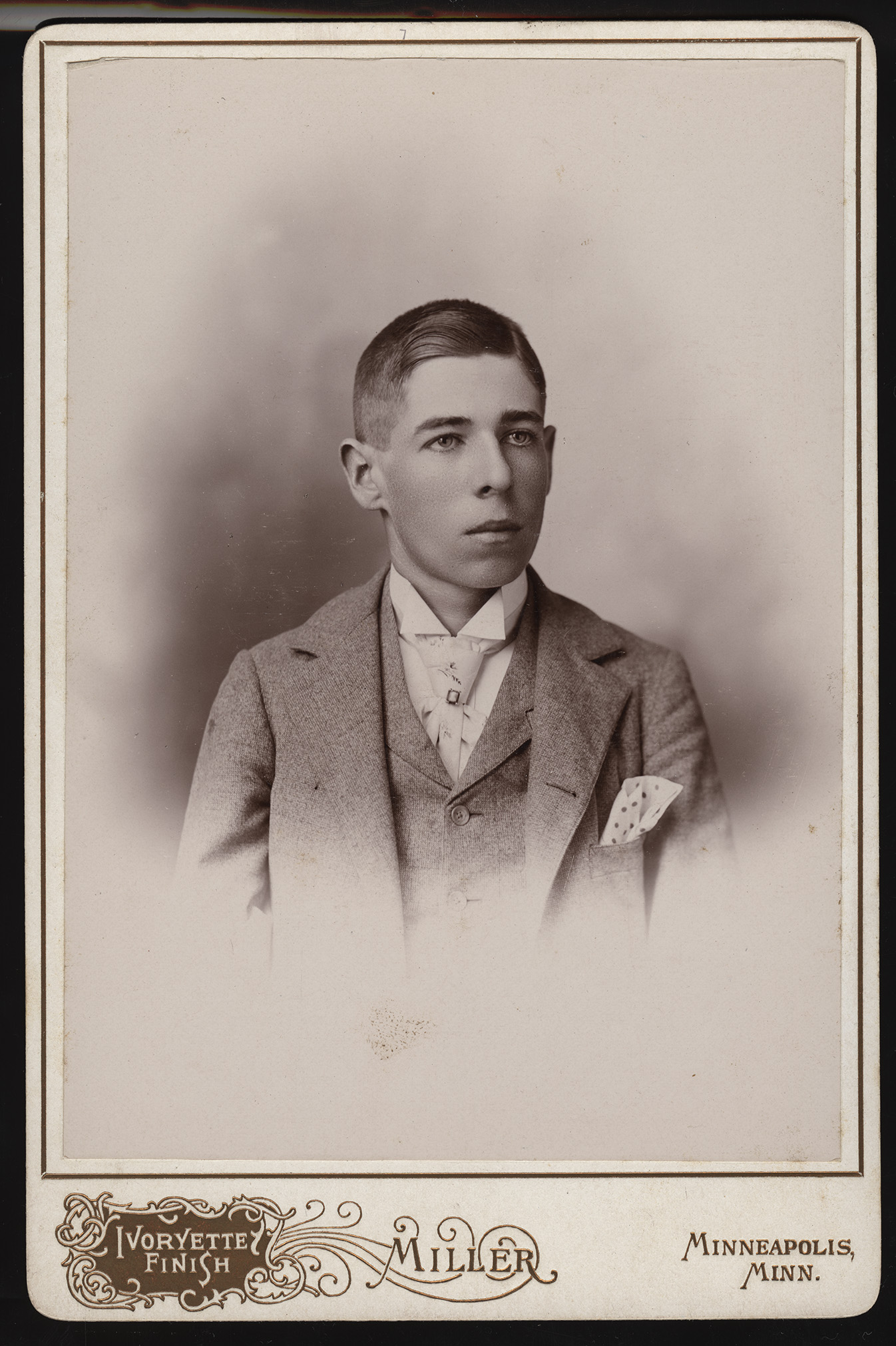

Frederick Curtis Gerard was the oldest son of Fred and Ella Gerard. Born in 1878, he shared a name with both his father and his older half-brother. SHSND B782.4. |

| Source E |

Ella and Fred’s second child, Birdie Ella, was born in 1880. SHSND B782.8. |

| Source F |

Charles Drummond Gerard, born in 1888, was the third child of Ella and Fred Gerard. SHSND 2013-P-007.00011 |

| Source G |

Florence Letitia, also called by her nickname Flossie, was the youngest daughter of Ella and Fred Gerard. She was born in 1893. SHSND B782.9. |

| Source H |

Learn more about the history of the fur trade in North Dakota by visiting the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum, the Missouri-Yellowstone Confluence Interpretive Center, or Pembina State Museum.