A history of Pemmbina, 1797-1895

By Gregory S. Camp

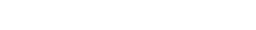

The small prairie community of Pembina offers a unique mosaic-a 1 microcosm, if you will-of some of the influential forces that have helped to shape the region and the state.1 During the course of its first hundred years, Pembina, located on the Red River in what is today northeast North Dakota, found itself at the center of controversy in a number of arenas. For the fur trade business, it was the site of fierce, sometimes violent, competition. For the Metis, it became an important staging area and one of many symbols of their growing sense of nationalism. International politics also played a brief role along the forty-ninth parallel, with the fate of a reborn Pembina community one of the chief sources of contention. It benefited from good economic times, suffered during busts, feared the floods and droughts, and worried about the possibility of Indian attack. First home to several tribes of native peoples, the area where Pembina was established ran the gamut of the frontier experience: fur trade site, colony, river town, shipping center, scene of international tensions, and finally, military outpost. In short, the Pembina region rode the tide of changing fortunes on the northern Great Plains. This article addresses the almost one hundred years between the establishment of the first fur trade post in Pembina in 1797, and the end of its era as a military post with the closing of Port Pembina in 1895.

In the 1780s, when the young United States was struggling with the Articles of Confederation and foreign intrigue west of the Appalachian Mountains, another story was unfolding in the middle of the North American continent. Here, along the Red River of the North, British fur traders from the North West Company of Montreal were sounding the economic waters for the positioning of a fur trade post in what to that point had been Yanktonai Sioux territory. Fully cognizant of the French fur traders' interdependence on the Chippewa and Cree, the North West Company sought to encourage these tribes to migrate to the prairie where the fur trade had heretofore been unexploited. Alexander Henry the Elder was among a host of traders to see the possibilities in this remote area. He knew, too, that Chippewa and Cree participation was of the utmost importance. Although the 1780s proved to be a bit too early for a concerted effort in the Red River Valley of the North, the fur trade became quite active in the next two decades.2

Beginning in 1793, the North West Company erected a semipermanent post under the control of Peter Grant at what is today St. Vincent, Minnesota. The Yanktonai Sioux, however, forced Grant's post out of the Red River Valley. Undaunted, the North West Company simply waited a few years before giving approval for yet another venture at the confluence of the Pembina and Red rivers. In 1797, Charles Jean Baptist Chaboillez erected a small post on the south bank of the Pembina River at the point where it meets the Red River. Chaboillez sought to immediately expand his operations by establishing small subposts at strategic locations across the Red River Valley. It was at this time reports were received concerning the virtually untapped fur-yielding Hair Hills (now known as the Pembina Mountains) and the Turtle Mountains, which convinced company officials of the potential of this remote part of North America. Indeed, Chaboillez was not the only trader in the region. In his journal, Chaboillez notes another post, confirmed by David Thompson's report of a site known as "Roy's" or "Le Roy's" near the confluence of the Salt (now known as the Forest River) and Red rivers in 1798. In addition, John MacDonell had a fur trade post as far west as the Souris River at the same time. By 1799, however, steppedup Sioux attacks eventually forced Chaboillez and other traders to abandon their places of business. Despite these setbacks, the economic die had been cast for further exploitation of the region.3

The return of the fur trade in strength to the Red River Valley is perhaps best embodied in the person of Alexander Henry the Younger. The nephew of the already famous Alexander Henry the Elder, this intrepid trader left some of the best records available of the fur trade era on the northern plains. Arriving first in 1800, Henry cautiously made his way up the northerly flowing Red River in search of a location for a proper headquarters. His Chippewa trading partners were understandably nervous about the prospect of meeting a Sioux war party. Still, the party pressed on until coming upon the confluence of the Park and Red rivers. Henry constructed his headquarters approximately one-quarter of a mile from the mouth of the Park; within a few months, however, the site proved to be a less than ideal spot for directing the trade. For one thing, the various Chippewa bands who were trading with Chaboillez were not willing to venture that far south for fear of incurring the wrath of the Yanktonai Sioux. As a result, Henry packed up his goods and moved northward to Pembina, a familiar site to both the North West Company and its Chippewa friends. From this location, Henry began his operation which literally changed the face of this part of the northern plains. The trade at once encouraged the Chippewa to return to the Dakota prairie, furthered competition with the Hudson's Bay and XY companies, and helped to establish Metis identification with the Red River Valley as a homeland.4

As it turned out, Henry's choice of Pembina was a good one. The Sioux were, by and large, absent during the next half decade or so, which provided Henry and his Indian trading partners some time to put down roots and grow. Henry's abilities as an administrator became immediately apparent when he began to exploit the fur-producing regions, first around his headquarters, then at some distance from it. For instance, Henry was wise enough to realize that overtrapping was a very real danger in an operation of the size he envisioned. As a result, the North West Company trader authorized the building of many subposts at strategic sites. Some of these small, seasonal posts included operations in the distant Turtle Mountains, the Pembina Mountains, near Devils Lake, and on the Park, Goose, Salt, Rat, and Buffalo Rivers. When one site showed signs of overtrapping, Henry shut it down to allow for natural restocking. With this technique, Henry hoped to be able to harvest furs indefinitely.5 Henry's fur trade post in Pembina, fed by its chain of subposts, became the North West Company's largest and most important fur trade operation in the Red and Assiniboine river region. Evidence of the success of the Pembinabased exchange is perhaps best seen in the many river posts that sprang up to compete for the fur trade in this area.6 The years 1801-1805 helped to solidify Pembina as a primary place of exchange for the next several decades, despite the vicissitudes (changes) of the fur market. Still, the "Golden Age" in and around Pembina would not last forever.

As early as 1808, it became apparent to Henry and his trading partners that Pembina could not sustain the large fur harvests of earlier years. There were a number of reasons for this decline. The population of the participating Cree and Chippewa at Pembina had increased significantly. Indeed, Pembina was now something of a hub community, with its economic spokes making their way north, west, and south. This put a strain on food supplies in the region. By 1808 most of the food was still obtained through hunting, although the Chippewa were increasingly engaged in planting around Pembina itself Also of importance was the increasing number of Sioux attacks after 1805. Although the Chippewa and Cree were numerous enough to defend themselves and their gains in the valley, they were nonetheless now constantly on guard against attack. Pelt yields also showed signs of decline between 1806 and 1812. Still, the end of the first phase of Pembina's history was not entirely wrapped up in the fur trade; there were other forces at work which proved even more unpredictable.7

At the outbreak of the War of 1812, the Red River Valley, in general, and Pembina, in particular, were about to undergo dramatic changes. One of these changes was the growing population and influence of a group known as the bois brules, or Metis, the French word for "mixed-blood." Joining first the French and then British traders, Chippewa and Cree women, in particular, intermarried with the Europeans and produced a sizable mixed-blood population. Many of these mixed-bloods worked in the fur trade as hunters and trappers or general laborers.

By the end of Henry's tenure, the Metis considered themselves neither Indian nor white; indeed, a good many considered themselves superior to both. They adopted the bison culture, with modifications, from the Plains groups around them. They incorporated European religion, primarily Roman Catholicism, and they emphasized education. By 1812 the Metis had become important players in the economic and social life of the Red River Valley. When the fur trade waned, they remained as first-rate hunters. It was not surprising that by the second decade of the nineteenth century, the Metis referred to themselves as the "New Nation." Metis identity was awakened, to a certain extent, by another highly important part of the Pembina story: the Selkirk Colony.8

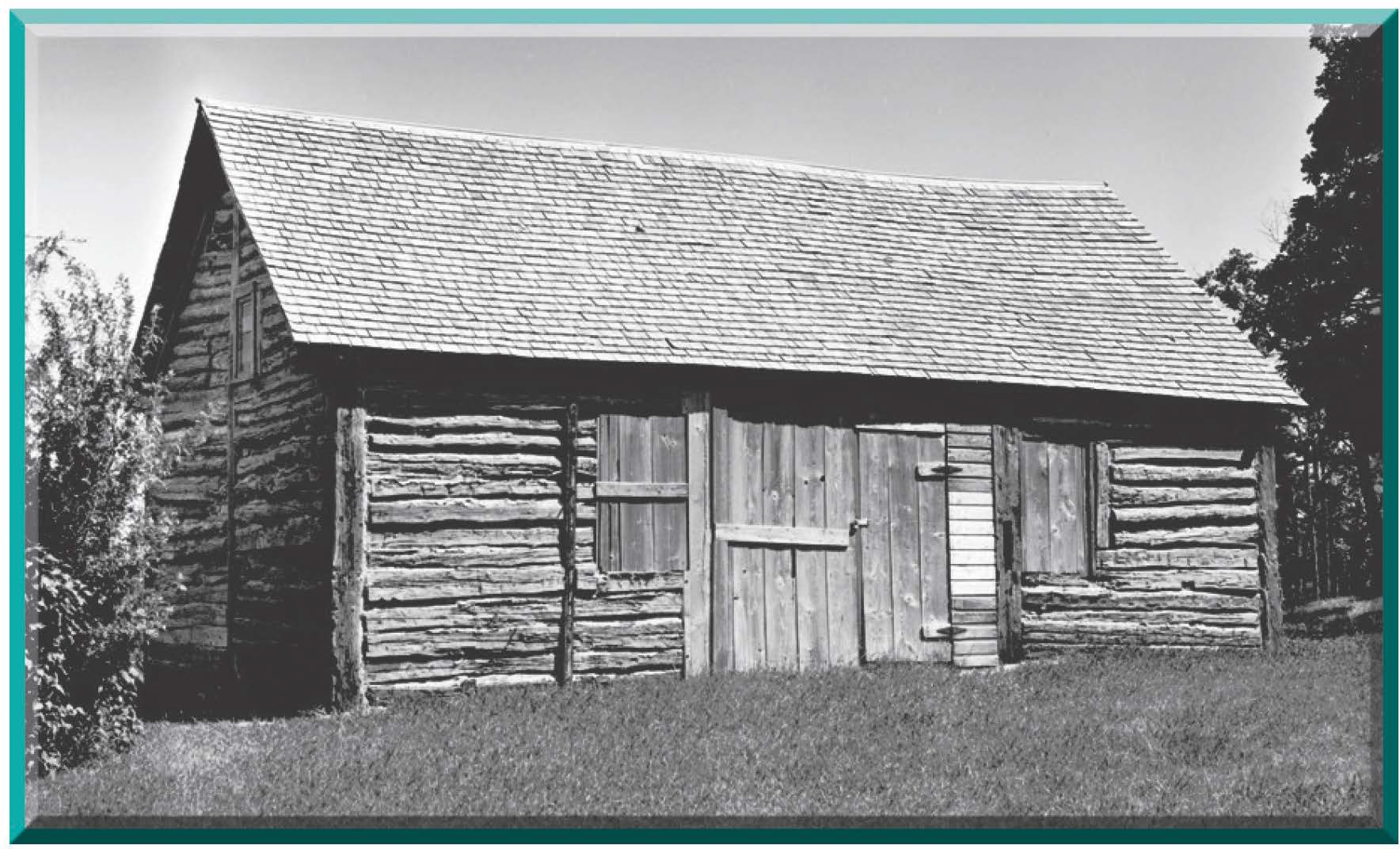

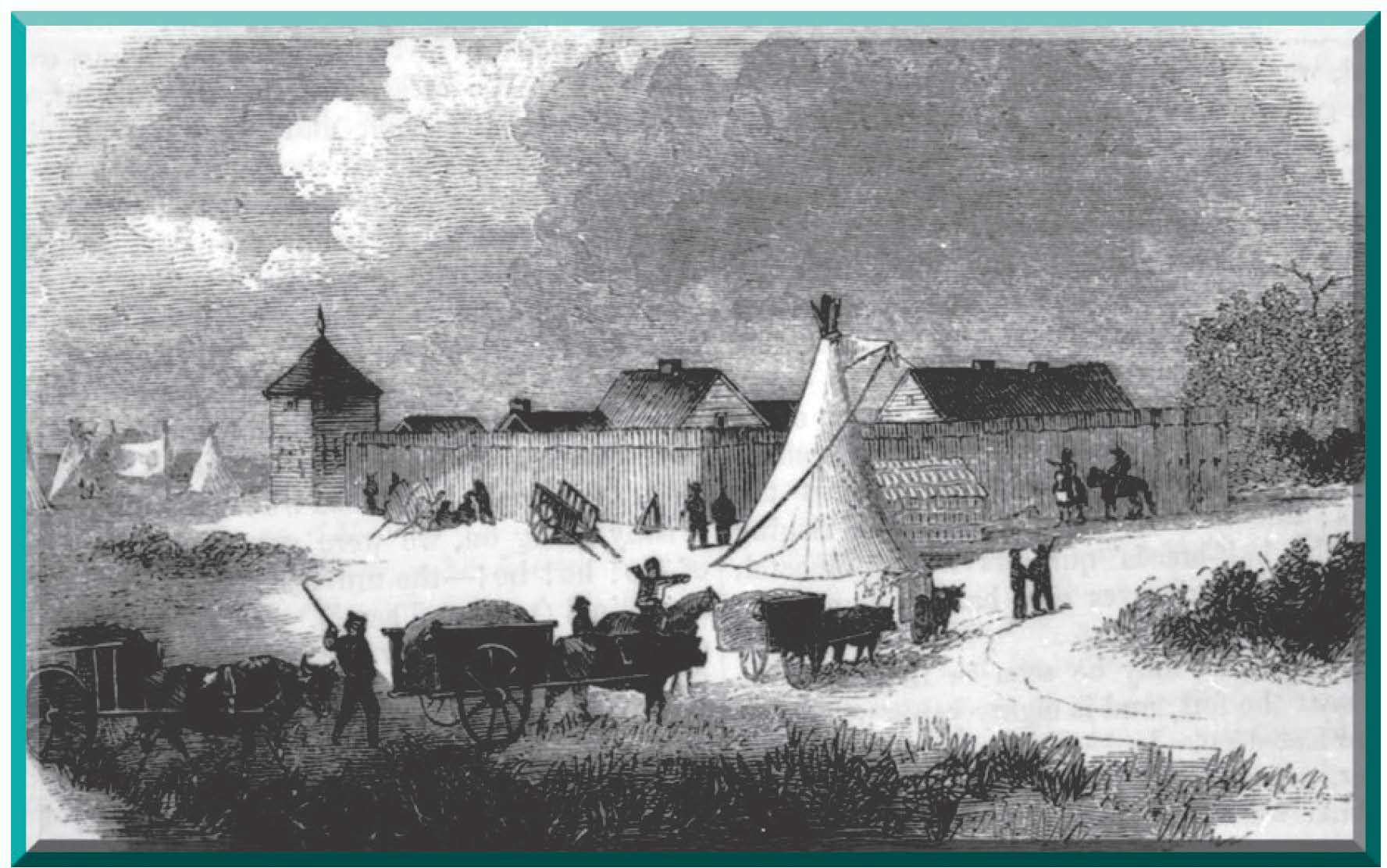

In 1811-1812 settlers under the sponsorship of Thomas Douglas, Fifth Earl of Selkirk, began arriving in what is today Manitoba to establish an agricultural colony in the Red River Valley. Selkirk was a major stockholder in the Hudson's Bay Company, and his ambitious plan to place a colony in the midst of a North West Company stronghold was understandably resented in Montreal. Because of logistical problems, the small group of colonists put up at the confluence of the Pembina and Red Rivers and called their settlement Fort Daer. The North West Company still used this site as a trading center, so the establishment of an agricultural "station" so close to their property was disconcerting. The new structures for the colony were built on top of the old Chaboillez post (1797-1798), and were literally a stone's throw from the Nor'Westers, the term given to the rugged employees of the North West Company, who were located across the Pembina River.

It was apparent that it was only a matter of time before the two representatives of opposing fur trade interests would clash. By 1812 the fur trade in general had undergone something of a decline in the western reaches of the Hudson's Bay basin. The areas yet to be successfully or fully exploited lay to the west. Both the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company coveted the Red River Valley more for its strategic location as a middle ground between eastern and western Canada than for any remaining fur harvests which might be taken.

In the midst of this corporate war came the Metis. They saw the valley and Pembina not as an important cog in a corporate machine, but as a place to call home. Nonetheless, their abilities as hunters and soldiers made them invaluable to the Nor'Westers. In many regards, however, the Metis were pawns of the warring factions, especially the North West Company. After events such as the Proclamation of 1814, in which the infant colony sought to regulate bison hunting and trade in general, the Metis saw themselves less as part of a fur trade rivalry and more in a fight for their own land and interests.9 Despite the conflict between fur trade interests, known as the "Pemmican War," Pembina had already made its mark on the region. Indeed, as a result of negotiations between the United States and Great Britain, the residents of this remote part of North America witnessed the drawing of a tentative boundary at the forty-ninth parallel. This imaginary line was all but ignored by both white and Indian inhabitants, not to mention the two governments. White civilization, however, was making its slow but inexorable march westward and had, at last, reached the center of the continent. Another sign of this intrusion was perhaps quieter, but no less powerful in its long-term influence.

The introduction of organized missionary efforts at Pembina opened a new chapter for that community. Since Henry established his post in 1801, Pembina had grown to prominence in the plans of both the Hudson's Bay and North West companies. With this rise in economic stature and the growth of a non-white population there, organized Catholic missionary agencies expressed interest in establishing a presence among these people. Since establishment of the "border" in 1818, there was some confusion as to which diocese or jurisdiction the Metis and Chippewa should belong. Indeed, the exact location of the forty-ninth parallel was in question and would be measured and remeasured a number of times between 1823 and 1872. For the church, however, the exact location of their new wards was less important than the condition of their souls.10

In an attempt to address both location and population considerations, the first Catholic missionaries sent to the Red River Valley established a headquarters at Fort Douglas, which became Fort Garry and is now Winnipeg, Manitoba, in 1818. They built a smaller mission at Pembina shortly thereafter. According to tradition, Lord Selkirk was apparently impressed with a messenger from Pembina who traveled to Montreal to see him, despite great hardships. When asked what reward he might bestow on the messenger, the traveler was said to have asked for a priest for his colony at Pembina. At any rate, during the spring of 1818, Fathers Norbert Provencher and Severe Dumoulin and a teacher named William Edge went to the Red River Valley with the intention of serving the settlers and proselytizing amongst the Indians and mixed-bloods. When crop failure forced many of the whites from Fort Douglas back to Pembina that same year, this small outpost of Catholicism found itself host to more than three hundred parishioners-many times larger than the congregation at Fort Douglas. To the delight of the missionaries, the Metis people were eager to learn all they could of Catholicism and proved to be among the most devour followers of the faith in the West.11

The first mass at Pembina was served on September 18, 1818, in a temporary residence set up for the occasion. The school building, another temporary shelter, doubled as Father Dumoulin's place of residence. During a special Christmas service in 1818, the priest proposed constructing a permanent building to serve as church and school for the growing community of mixed-bloods and whites. By May 1821 the new church was opened with prayers of thanksgiving and celebration. Still, the parish was very poor. The resources of the small mission were strained further during the winter of 1821-1822 when 150 newly arrived Swiss settlers faced the very real possibility of starvation. All of Father Dumoulin's hard work was headed for an abrupt conclusion, however, as workings in the political world once again made their impact on distant Pembina.12

During the winter of 1822, the Hudson's Bay Company came to the conclusion that the Pembina settlement was indeed in American territory. Stephen Long's visit to Pembina in 1823 on behalf of the United States government's survey team verified this finding also, and only served to hasten British withdrawal. When Father Dumoulin was thus forced to withdraw again north to Fort Douglas, he promptly transferred back to Montreal. In the wake of this turn of events, it appeared for a time that Pembina as a village and a parish was doomed. A sizable number of Pembina settlers moved northward, while still others moved further south, some of them later helping in the establishment of St. Paul, Minnesota. Nonetheless, some residents refused to leave the place that had become home. For approximately twenty years, between 1818 and 1838, Pembina was served by mission priests and did not have permanent parishes.13

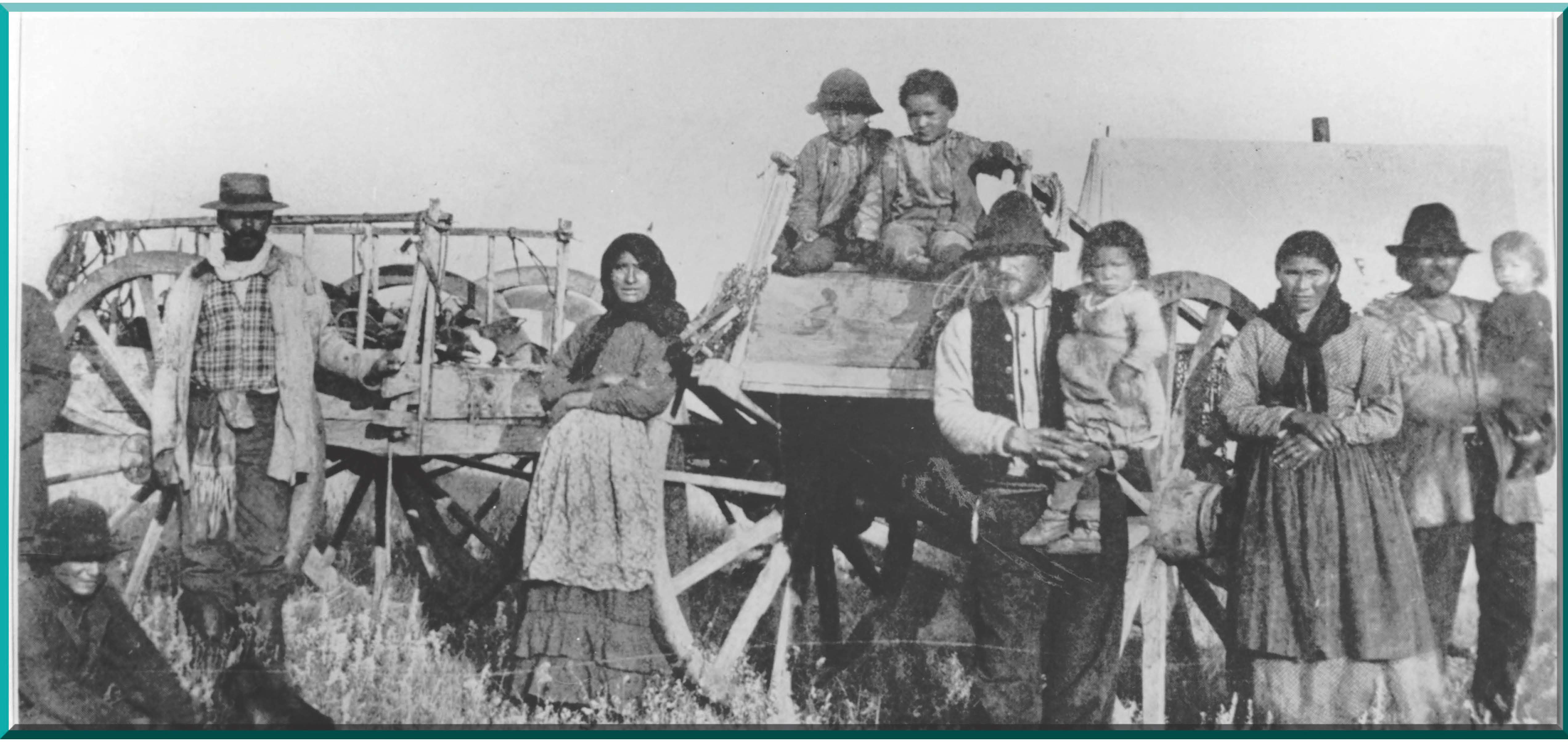

Between 1823 and 1838, life in Pembina was a threadbare existence. No longer a primary trade site for the Red River colony to the north or for the fur trade of a generation before, the small community fell into disrepair and poverty. The mixedbloods who chose to stay worked for whites to the north as farmhands or as hunters. In fact, it was the Metis bison hunt that helped to keep Pembina alive during these lean times. Prior to one of their massive hunts, the Metis would often cross the line and muster their forces on the familiar prairies around Pembina in preparation for the bison chase. The Metis developed specific rules as to the taking of bison during these hunts, rules which would ultimately help provide further definition of their nationhood. As it was, the bison hunt was the quintessential Metis activity, glorifying and embodying all that the mixed-bloods held dear. These chases, in which the entire family would take part, would at times even involve participating clergy-much to the chagrin of the Hudson's Bay Company. Father George Antoine Belcourt, who was himself to establish a church at Pembina and then St. Joseph (now Walhalla), is perhaps the best example of this. During the 1840s, however, a combination of Metis nationalism and free trade collectively helped to revitalize Pembina.14

Although the fur trade in Pembina and the area along the ill-defined border between American and British possessions never completely died after the Pemmican Wars of the second decade of the nineteenth century, it was not until near the middle of the century that the fur trade was revitalized. This time, however, there were forces at work which were quite new, and this combination of the old and new created a situation far-reaching in scope.

In 1843 Norman Wol&ed Kittson, at the behest of his trading partners in the American Fur Company, established-or reestablished-a fur trade post headquarters at Pembina. Located just a few yards from Alexander Henry the Younger's 1801 post, Kittson and his sponsors hoped to tap what promised to be a rich fur trade market from the Mouse River in the west to Rainy Lake River in the east. This operation, along the forty-ninth parallel, would also take advantage of Metis dissatisfaction with the Hudson's Bay Company's monopoly on trade in the Red River colony. Kittson was quite aware of the mixed-blood bison hunts on the plains to the south and west of his headquarters. What better place than Pembina for one seeking to trade with the Metis?15

o augment his opportunities, Norman Kittson established subposts at Pembina Mountain, the Turtle Mountains, on the Mouse River, and to the east, at Rainy Lake. These posts would offer cash or trade scrip in return for Metis and Indian pelts and hides. Because the Hudson's Bay Company had limited power to act, any attempts made to stop the free trade would have to involve the mixed-bloods, something the British company would rather have avoided at that time. Moreover, in the tense political atmosphere of the 1840s, the leadership of both the Hudson's Bay Company and the British government were concerned about U.S. expansionism and wondered if this was but another Yankee ploy. The American Fur Company was aware of British concerns and also used it to their advantage.16

Norman K.ittson's plans for the Pembina operation included making it a major source of trade competition for the Red River colony to the north, encouraging illegal trade across the forty-ninth parallel, and allowing the community to become a warehouse for furs brought from north of the border. Central to his plan were the Metis and the importance of Pembina to that group. Kittson's trading partners and his choice of headquarters did not prove a disappointment. By 1845, the Red River colony was complaining of the American presence at Pembina and the heavy Meris involvement there. "Kittson's Fever" was the disparaging term the British used to describe the problem, while the Meris happily exclaimed, "Le commerce est libre!" [Commerce is free!] Indeed, by 1849, when the issue of free trade was pursued in court between the Hudson's Bay Company and the Meris, the latter won. During a trial of free traders, or smugglers, as the British referred to chem, the colony courthouse where proceedings were held was surrounded by hundreds of Meris. While the verdict was guilty, no penalty was assigned. It thus appeared chat the mixed-bloods could take on the powerful Hudson's Bay Company and have its own way. It was a heady experience for the increasingly independent Meris, but was ultimately short-lived. On the American side of the forty-ninth parallel, events at Pembina were changing yet again.17

In 1849, Pembina was host to another United States' military survey team, led by Major Samuel Woods and Captain John Pope. The expedition's objective was to once again measure and mark the exact location of the forty-ninth parallel. This visit was in part to "show the flag" in the face of heightened tensions along the border, bur it also served as a harbinger of a future permanent military post at Pembina. Both Henry Hastings Sibley, Minnesota's territorial congressional delegate and employee of the American Fur Company, and Alexander Ramsey, Minnesota's first territorial governor, wanted a military fort at Pembina as a precursor to negotiations with the Pembina and Red Lake Chippewa bands for ceding lands in what is today North Dakota and Minnesota.18 Just across the Red River to the east, Minnesota had been named a territory in 1849 and was growing so quickly chat it became apparent that statehood was not far behind. Indeed, six new counties were created in Minnesota Territory, including part of what is today North Dakota, between 1849 and 1851. One of chem was a massive tract of land known as Pembina. When the territorial governor, Alexander Ramsey, visited the community in 1851, he was surprised to find a town of some 1,100 people, most of them Meris, with more than two thousand acres under cultivation. Ramsey realized chat chis area had true market potential for St. Paul. In his mind, the vast tracts of land in the northwest had to be ceded in preparation for the coming white settlers.

The officers in charge of the 1849 operation to mark the forty-ninth parallel surveyed the location of the border between Canada and the U.S., spoke to several Indian and Metis residents, and even stopped by for a visit at a Hudson's Bay post just north of the line. The verbal and written report the two officers prepared was anything but complimentary of the British and their treatment of the Indians and Meris in the Red River Valley. Colonial leaders, most of whom considered the unrest among the Meris to be largely the fault of Norman Kittson and his business practices, were particularly incensed when told about the verbal attacks made against their administration concerning their treatment of the Indians. Still, the company's worst fear, a permanent American military post, was not realized. After their survey was complete, the U.S. forces withdrew; a fort would not be constructed near Pembina until 1870, and then for different reasons.19

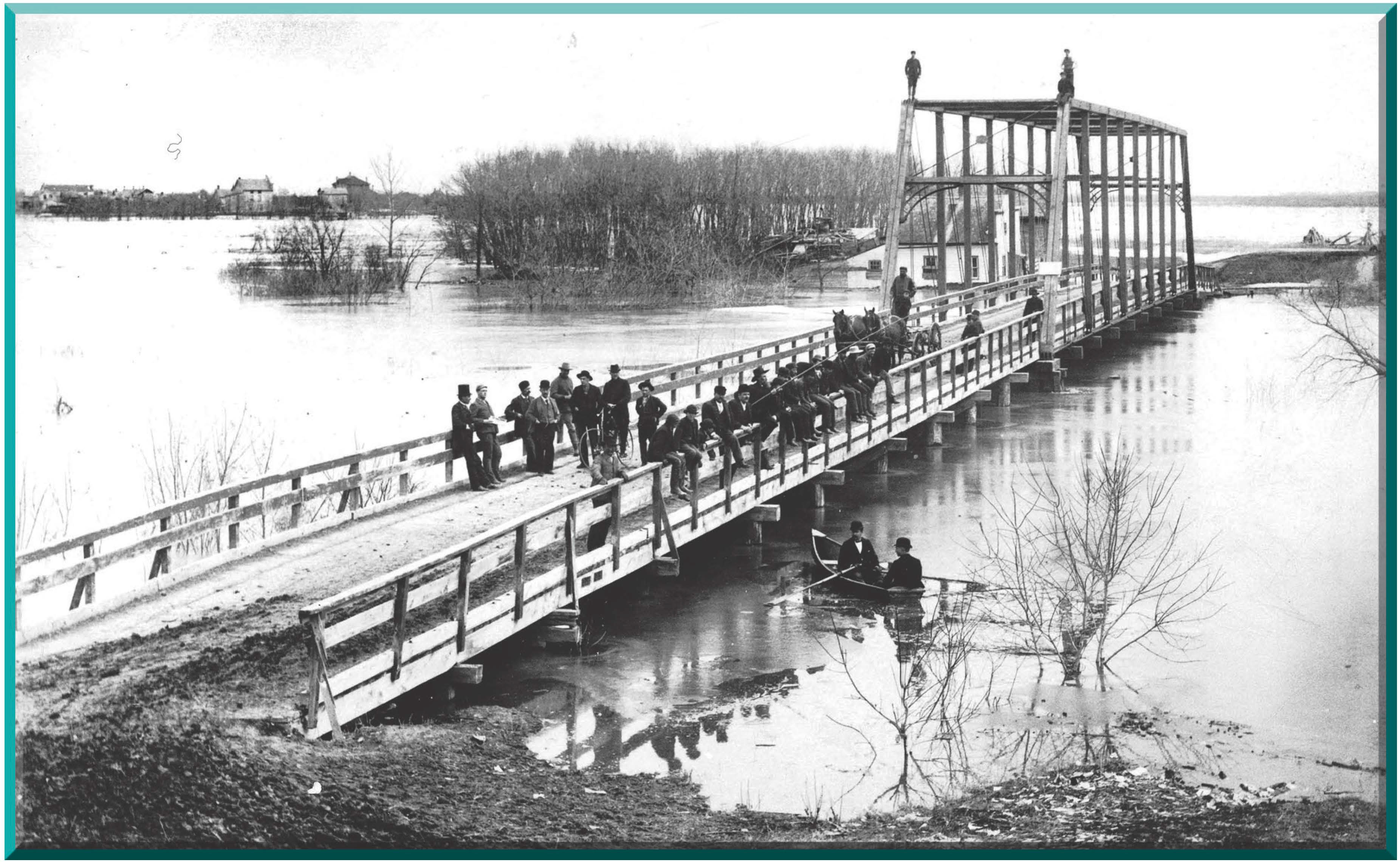

Although Norman Kittson's Pembina operation enjoyed some good years between 1843 and 1849, it decreased in productivity after 1849. Flooding, a yearly spring threat along the Red and Pembina Rivers, had done its share of damage to this border post. Even Father Belcourt moved from the community of Pembina to the Pembina Mountains in the west as a result of rising water. Kittson followed suit, but still maintained a post at Pembina. Kittson hoped chat a treaty between the United States and the Pembina and Red Lake Chippewa would help to solve many of the problems he was having with his Indian trading partners. The Meris, too, were hopeful chat the United States would provide them with some recognition of their claims in the Red River Valley. Many looked upon the meetings between U.S. representatives, led by Alexander Ramsey, and the Chippewa in 1851 at Red Lake Crossing as a solution to a persistent problem. The treaty Ramsey negotiated chat year was never ratified in the U. S. Senate, however. It would not be until 1863 that a treaty was finally worked out between the Chippewa and the United States. Under this agreement, the Meris were not given independent status but were instead lumped together with their full-blooded relatives in the negotiation procedures. This was not to the liking of either the full bloods or Meris. The most the Meris received were promises of land scrip for 160 acres each in the area to be ceded. While Pembina continued as a hub for a waning fur trade operation, its place as a center for westward-moving white settlers would have to wait.20

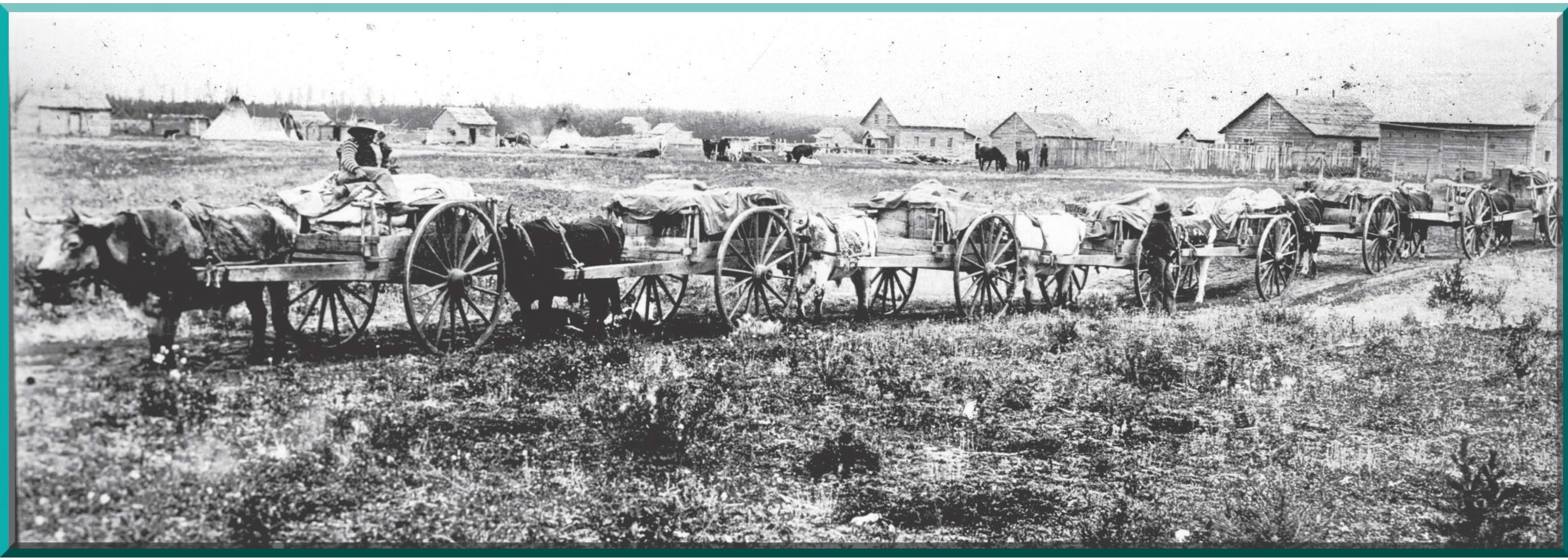

Norman Kittson realized that the lucrative profits of the 1840s were not to be repeated in the 18 50s. It was the Red River cart trade chat would increasingly take the place of the fur exchange as the main source of revenue in chat decade. The cart trade had in fact begun several decades before, and had proven a reliable mode of transportation on the rugged prairie. Built entirely from wood, the Red River cart was a marvel of engineering simplicity and pragmatism. An enduring symbol of the Meris and Red River settlement, descriptions of the cart can be found as far back as Henry's journal in the first decade of the nineteenth century. At that time it was used for moving supplies from one subpost to another, or for retuning prepared pelts to the factories in the north. By the 1840s, the Meris were using these carts in their bison hunts and in the trade chat cropped up between the Red River colony in Manitoba and the infant town of St. Paul. By the 1870s, the Red River cart trails were clearly marked on the open prairie and followed the western edge of the Red River Valley, the shoreline of the ancient glacial bed of Lake Agassiz. Another route went along the eastern shore of this lake and into the woods, presumably to avoid contact with hostile Sioux bands. For Kittson and the Pembina communiry, these Red River cart caravans marked the decline of the fur trade and the advent of a time of commerce.21

St. Paul continued to grow as a result of the cart trade making its way south from Pembina and the Red River. By 1857 Canadian fears were very real concerning a possible American takeover of the Red River Valley. This takeover occurred, however, not as a result of military action, but by the sheer force of numbers which toppled the British hold on the region. To many, the Hudson's Bay Company's top-heavy policies favoring the eastern part of Canada were to blame; that, and their insensitiviry toward the Metis. When reports circulated that the Metis had petitioned the United States for military help from Fort Snelling, the British sat up and took notice. However, the real threat to British power was not military but economic.22

Besides the Red River carts, steamboats were to play a small but meaningful role in the history of the valley in general and Pembina in particular. After the United States established Fort Abercrombie in 1857, a stage and freight route blazed between the river fort, two hundred miles south of Pembina on the Red River, and St. Paul. The Hudson's Bay Company had set up Georgetown down river (just north of present-day Fargo on the east side of the Red River) as a stopoff point for the steam vessels that made their way northward toward Pembina and ultimately, Fort Garry. The steamboat trade was not to last long, however, as it proved too costly for the St. Paul sponsors to maintain. The colony also tried to continue service between Pembina and Fort Garry, but, in the end, they, too, were unsuccessful. Nonetheless, a custom house was established in Pembina to act as a center for what would optimistically be a lucrative business for the Yankee traders at that border town and in St. Paul.

By 1861 Pembina consisted of only around a dozen or so log buildings used in an official capaciry or occupied by those involved in business or churchrelated activities. Nonetheless, a good many Metis still frequented the area during the hunts. The rest tended to reside to the west in the viciniry of St. Joseph in the Pembina Mountains where Fathers Belcourt and LaCombe had moved their mission. Still, Pembina continued to act as an important port of entry in the trade between Red River colony and St. Paul. Only the blindest company and government officials in Montreal and London failed to realize that the Red River colony's trade now flowed south to St. Paul instead of north to the factories of the Hudson Bay. Such a turn of events was clearly unacceptable, and, as a result, the British government revoked the charter of the increasingly inefficient Hudson's Bay Company, a charter that had been in effect since 1670.23

Although the Hudson's Bay Company had fallen on bad times with the revocation of their charter, Pembina, too, was in an economic downspin. Prior to the outbreak of the American Civil War, Pembina and the large region around it anticipated the arrival of the railroad and the settlement which inevitably would follow. The war, however, changed this upbeat assessment of the village and its economic potential. There were other contributing factors as well. During the decade of the 1850s the community of St. Joseph in the Pembina Mountains had taken Pembina's place as a major gathering site for the Metis and what remained of the fur trade. While the cart trade continued after 1860, the town of St. Cloud, Minnesota, took on increased importance as a stopoff point before reaching St. Paul, and Pembina's role as host to the fur trade and cart traffic was reduced. In Pembina itself, a postmaster (Joseph Rolette and Charles Cavalier both served in this position) and a custom house were still maintained, although they became less necessary with the passing of the years. Surveying parties made their way to Pembina after a county bearing the same name was created in 1867, occupying most of what would become northeastern North Dakota. St. Joseph was designated the county seat with the usual array of county government officials, some of the best-known personalities of the region. Once again, though, events outside the community itself, in particular Indianwhite relations in the wake of the 1862 Minnesota Uprising, would affect the history of Pembina.24

For white settlers living in Minnesota, the early 1860s were a time of tension and fear. Rumors of Indian uprisings had been rampant for some time before the actual outbreak of hostilities in 1862, and were intensified with the bad news of Union defeats and horrendous casualty counts in the early days of the Civil War. When the outbreak did occur, the Santee Sioux lashed out at whites for a variety of reasons, ranging from the latter's cultural arrogance to their squatting on Santee land. On August 18, 1862, the powderkeg finally exploded, sending shockwaves as far away as the prairie around Pembina. Fear of an imminent Indian attack was the topic of conversation and the object of preparations. This threat of war exacerbated the decline in Pembina's efforts to regain its stature as a center of trade. Ironically, the Metis, among the bitterest enemies of the Sioux, had made peace with their prairie foes in 1860 in an effort to end their long-standing differences. The mixed-blood settlement at St. Joseph and what remained of Pembina were the unofficial capitals of the Metis, and they were understandably concerned about protecting them. Nonetheless, the United States government entered the picture almost a decade later and began construction of a fort to protect American interests from the Sioux. By the time the government got around to planning the fort in question, the chosen sites had been narrowed to either St. Joseph or Pembina.25

The recent problems with the Sioux Indians were not the only reason for the desire to construct a post in Pembina County. The future course of the railroad was another consideration, as were events north of the border. In 1870 the Hudson's Bay Company ceased to operate as a political entity when Canadian troops arrived in August. Because their status had never been decided to the Metis' satisfaction, a series of confrontations collectively known as the Riel Rebellions swept Manitoba and points west. The sizable population of Metis living in the Pembina and Turtle Mountains were understandably interested in the outcome of events in Canada. Moreover, Canadian officials had expressed concern to Washington about the possibility of cross-border interaction in the event of the outbreak of hostilities.26

Colonel George Sykes and Captain David Heap, who had been sent on yet another mission to redraw the location of the forty-ninth parallel, relied on reports of periodic flooding and came to the conclusion that Pembina was an unsuitable place for a large post. Therefore, St. Joseph was chosen and construction began on the fort. There was, however, a considerable protest over the selection of St. Joseph from the Pembina residents who naturally saw real economic opportunity with a military post nearby. Citizens, especially those with business interests to be served, wrote letters to a number of government officials, among them General William T. Sherman, listing the shortcomings of a post at St. Joseph. Chief among the complaints were the difficulties encountered trying to resupply the fort via the shallow Pembina River. There was support for moving the fort nearer to Pembina from other sources, as well. Alexander Ramsey, whose experience in the region during the past two decades garnered respect, wrote to General Sherman of the sagacity (wisdom) of a fort nearer to Pembina. The correspondence had its desired effect. The recently begun construction near St. Joseph was halted, and in July, the War Department made the decision to build the fort in Pembina. By August of 1870, construction had begun south of town on what passed for high ground there.27

At the time the fort was constructed, there was little at Pembina in the way of permanent buildings. These included the custom house, a mission outpost, and the cabins of Cavalier and the other very small number of white residents-not much different, in fact, from what had been reported nearly ten years earlier. In the meantime, to the south, small settlements had taken root in Grand Forks and Fargo since the time of steamboat trade. By 1871 telegraph poles and lines were stretched from Fargo to Pembina; moreover, stagecoach service also arrived at Pembina around the same time, a result, no doubt, of the construction of the fort and the rising interest settlers were showing in the Red River Valley. In addition, the St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Manitoba Railroad Company began construction of a line from Winnipeg southward in conjunction with the Canadian Pacific Railroad Company on the eastern side of the Red River. The same railroad company had tracks already as close as Crookston, Minnesota, in 1871 with grade work taking place well to the west of that. By 1873 Pembina had more than five hundred residents and forty permanent buildings, including eight saloons and other stores. Marshal Judson LaMoure now kept law and order. The custom house, previously on the verge of falling into disuse, now thrived with business. There is little doubt that the construction of the fort marked a watershed period for Pembina's evolution as a community.28

Fort Pembina continued to serve its purposemaintaining order and providing stability-for more than twenty-five years. In 1895, however, when a fire swept the fort and destroyed a sizable portion of it, the War Department made the decision to discontinue its operation and sold what was left of the structure at public auction.29 During the decade of the 1890s, Pembina had grown beyond the need for, or at least its dependence on, the fort. Still, when the fort was gone, it marked another turning point in the history of the community. The Red River Valley was being touted in the East and in Europe as among the most fertile land in North America. Settlers from a variety of ethnic and religious backgrounds were swelling the population of the Red River Valley in general, and the Pembina region shared in that new boom. As a center for the fur trade, home to the Metis, and a military post, the town had come through a tumultuous adolescence and was now entering adulthood as a farming community. At the turn of the twentieth century, Pembina would have a new role to play in the life of the new state of North Dakota, in the northern plains, and in the United States.

About the Author

Gregory S. Camp is associate professor of history at the University of Mary, Bismarck, North Dakota. A native of Bismarck, he received his undergraduate training from Mount Marty College, his Master of Arts degree from the University of South Dakota, and his Ph.D. from the University of New Mexico. His academic specializations are colonial and frontier America, Native American history, and early national U.S. history.

Originally published in North Dakota History, Vol. 60.4:22-33 (1993).

- The name "Pembina'' is thought to be derived from a Chippewa word (Panbinan) referring to the edible red berries found along the banks of the Pembina and Red Rivers at the time. For an excellent history of the fur trade at Pembina, see Lauren W. Bitterbush, "Fur Trade Posts at Pembina: An Archeological Perspective of North Dakota's Earliest Fur Trade Center," North Dakota History, vol. 59, no. 1, (Wimer 1992), pp. 16-29.

- See Alexander Henry the Elder, Travels and Adventures in Canada and the Indian Territories between the Years I 760 and I 776, (Boston: 190 I) and Charles M. Gates, Five Fur Traders of the Northwest, Being the Narrative of Peter Pond and the Diaries of john Macdonell, Archibald N McLeod, Hugh Faries, and Thomas Conner, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1933) for company accounts of these early days in the woodlands of Minnesota and the Red River Valley of the North. The Chippewa accounts of these formative days come primarily from William Warren's History of the Ojibway People, (St, Paul: Borealis Press, 1984), a reprint of the original version found in the Collectiom of the Minnesota Historical Society, vol. 5, 1885.

- J.B. Tyrell, David Thompsons Narrative of His Exploration in Wt>stern America, 1784-1812, (Toronto: Publications of the Champlain Society, vol. 12, 1916), p. 25n.; Grace Lee Nute, "Posts in the Minnesota Fur Trading Area, 1660-1855," Minnesota History, vol. 11, no. 4, (December 1930), p. 367; Elliot Coues, New light on the Early History of the Greater Northwest: The Manuscript journal of Alexander Henry, far trader of the Northwest Company, and of David Thompson, official geographer and explorer of the same company, 1799-1814, (New York: Francis P. Harper, 1897) vol. I, pp. 80-81. Peter Grant offers a look at the Sauteux (Chippewa) Indians in LR. Masson, ed., Les Bourgeois de la Compaguie du Nord-Guest, (New York: Antiquarian Press, LTD, 1960), vol. I, pp. 307-366. Between 1797 and 1798, the Goose River was apparently the unofficial "boundary" between the Chippewa and Sioux hunting territories. See Harold Hickerson, "Journal of Charles Jean Baptist Chaboillez, 1797-1798," Ethnohistory, vol. 6, 1959, pp. 286-287.

- The XY Company was also known as the New North West Company: it merged with the North West Company in 1804. Coues, ed., New Light, I, pp. 64-93; Harold Hickerson, "The Genesis of a Trading Post Band: The Pembina Chippewa," Ethnohistory, vol. 3, no. 4; (Fall 1956), pp. 311-312; Gregory S. Camp, "The Chippewa Transition from Woodland to Prairie, 1740-1820," North Dakota History, vol. 51, no. 3, (Summer, 1984), pp. 43-44.

- Hickerson, Ethnohistory, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 315-117; Coues, New light, I, p. 250; Gregory S. Camp, "The Chippewa Fur Trade in the Red River Valley of the North, 1790-1830," in The Fur Trade in North Dakota, Virginia Heidenreich, ed., (Bismarck: State Historical Society of North Dakota, 1990), pp. 38-39.

- Coues, New Light, I, pp. 187-188.

- Hickerson, Ethnohistory, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 322-323.

- Marcel Giraud, The Canadian Metis, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1985), I, pp. 380-389; Jacquelyn Peterson, "Gathering at the River, The Meris Peopling of the Northern Plains," in The Fur Trade in North Dakota, Virginia Heidenreich, ed., p. 48; G. P. Stanley, The Birth o/Western Canada: A History of the Riel Rebellion, (London: 1936), p. 1 O; Arthur S. Morton, "The New Nation: the Meris," in The Other Natives, the Metis, Antoine S. Lussier and D. Bruce Sealey, eds., (Winnipeg: Manitoba Meris Federation Press, 1978), I, pp. 27-29. See also Jacquelyn Peterson, "Many Roads to Red River: Meris Genesis in the Great Lakes Region, 1680-1815," and Olive P. Dickason, "From 'One Nation' in the Northeast to 'New Nation' in the Northwest: A Look at the Emergence of the Meris," in The New Peoples, Being and Becoming Metis in North America, Jacquelyn Peterson and Jennifer S.H. Brown, eds.

- Arthur S. Morton, A History of the Canadian West to 1870-71, (Toronto: University ofToronto Press, 1973), p. 536; Douglas Hill, Opening of the Canadian West, (New York: John Day Company, 1967), p. 35; John Pritchett, The Red River Valley, 1811-1849, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1942), pp. 138- 146; Frederick Merk, ed., Fur Trade and Empire: George Simpsons]ournal, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931), p. 162; Alexander Ross, The Red River Settlement: Its Rise, Progress, and Present State, (Minneapolis: Ross and Haines, 1957, reprint edition), pp. 52-62.

- J.M. Belleau, Brie/History o/Old Pembina, 1818-1932, document in possession of the State Historical Society of North Dakota, rare document vault; H.V. Arnold, History of Old Pembina, (Larimore: 1917), pp. 96-101; James Reardon, George Antony Belcourt: Pioneer Catholic Missionary of the Northwest, 1803-1874, (St. Paul, North Central Publishing Company, 1955), pp. 32-34.

- Belleau, History of Old Pembina, 1818-1932, pp. 5-7.

- Ibid., p. 6.

- Ibid., pp. 6-7.

- G.F. Stanley, TheBritish o/Western Canada: A History of the Riel Rebellion, (London, 1936), p. 1 O; David P. Delorme, "History of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa," North Dakota History, vol. 22, no. 2, Quly 1955), p. 125; V Harvard, "The French Half-Breeds of the North-West," Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880), pp. 318, 322-323: Alexander Ross, The Red River Settlement: Its Rise, Progress, and Present State, 2"d edition, (Rutland: Charles E. Turtle Company, 1972), pp. 249-250.

- Clarence W Rife, "Norman W. Kittson: A Fur-Trader at Pembina," Minnesota History, vol. 6, no. 3, 1925, pp. 225-226; see also Article of Agreement between Norman Kittson and Henry H. Sibley, May 22, 1843, Henry Hastings Sibley Papers, microfilm copy at the State Historical Society of North Dakota of the originals located at the Minnesota Historical Society. Hereafter, reference will be made to Sibley Papers, and Peter Garrioch Diary, B 12, State Historical Society of North Dakota; Alvin Gluek, Jr., Minnesota and Manifest Destiny of the Canadian Northwest, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1965), pp. 48-62; John Pritchett, The Red River Valley, 1811-1849, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1942), pp. 138-146.

- Rife, Minnesota History, pp. 229-230; Nancy L. Woolworth, "Gingras, St. Joseph, and the Meris in the Northern Red River Valley: 1843-1875," North Dakota History, vol. 42, no. 4, (Fall 1975), pp. 18-19; Gluek, Minnesota and Manifest Destiny, (Toronto: University ofToronto Press, 1965) pp. 48-49; Joseph Brown to Sibley, January 23, 1836, Sibley Papers.

- Joseph Kinsey Howard, Strange Empire, (New York: William Morrow, 1951), pp. 59-60; WL. Morton, Manitoba: A History, (Toronto: University ofToronto Press, 1957), pp. 77-78; Elwyn B. Robinson, History of North Dakota, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1966), pp. 76-77.

- "Report of Major Wood, relative to his expedition to Pembina Settlement, and the condition of affairs on the North-Western Frontier of the Territory of Minnesota," House Executive Document 51, 31" Congress, l" Session, 1850; Serial 577, pp. 18-21, 22-30.

- See Ross, Red River Settlement, pp. 391-408, for a vitriolic rebuttal of the criticisms leveled against the colony in Captain Pope's report.

- For an account of Ramsey's voyage to the region in preparation for treaty negotiations, see J.W. Bond, Minnesota and Its Resources, (New York: J.S. Redfield, 1854), pp. 255-359. Although this treaty was never ratified, it did provide the basis for the 1863 and 1864 treaties with the Red Lake and Pembina bands of Chippewa. See Charles Kappler, Laws and Treaties, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904), vol. 11, pp. 853-855, 861-865 or Documents Relating to the Negotiation of Ratified and Unratijied Treaties with Various Indians, 1801-1869, RG 75, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Microcopy T-494 treaty no. 330 (1864.); House Executive Document, 1, 34'" Congress, 3,J Session, Serial 893. See also Martha Ellis, "The Meris and Land Fraud in Minnesota Territory," Seminar Paper, Department of History, University of New Mexico, (Pall 1984), p. 4.

- Vera Kelsey, Red River Runs North' (New York: Harper and Sons, 1952), p. 120; Grace Lee Nute, "The Red River Trails," Minnesota History, vol. VI, (September, 1925), pp. 279-282; Howard, Strange Empire, pp. 52-56. See also Ross, Red River Settlement, pp. 234-274, and Marcel Giraud, The Metis in the Canadian West, 2 vols., for a comprehensive look at the Meris.

- Howard, Strange Empire, pp. 67-71.

- Kelsey, Red River Runs North' pp. 126-132; See Lewis Henry Morgan, The Indian journals, 1859-1862, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1959), pp. 106, 112-130, for an account of a voyage aboard one of these early steam vessels on the Red River between Fort Abercrombie and Fort Garry.

- Arnold, History o/O/d Pembina, pp. 142-143.

- Roy W. Meyer, History oftheSanteeSioux, pp. 114-115; See also Charles S. Bryant and Abel B. Murch, A History of the Great Massacre of the Sioux Indians in Minnesota, ( Cincinnati: Rickey and Carroll, 1864) and Isaac V. Heard, History of the Sioux War and Massacres of l 862 and 1863, (New York: Harpers and Brothers, 1863) for period accounts of the uprising.

- Howard, Strange Empire, pp 111-114, 132-140.

- William D. Thomson, "History of Ft. Pembina: 1870-1895," North Dakota History, vol. 36, no. 1, (Winter 1969), pp. 19-20; Robert W. Frazer, Forts of the West, (Norman University of Oklahoma Press, 1980), third edition, pp. 112-113; see also Ft. Pembina Post Returns, State Historical Society of North Dakota, microfilm copies of the originals located in the National Archives, Washington, DC, roll I, July 1870.

- Thomson, North Dakota History, vol. 36, no. 1, p. 30.

- Ibid., pp. 32-36.