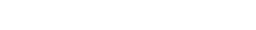

The second supporting question, “what economic trends influenced ranching in North Dakota prior to 1900?” helps students use primary sources to unwrap the context of the time and topic being examined. Ranchers arrived in northern Dakota Territory a little later than farmers. This was due in part to the later development of railroad access in the western part of the state and in part due to the continuing effort of the Oceti Sakowin (Lakota) to defend their hunting area, treaty lands, and way of life. After the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876 the Native American nations were relocated to reservation areas by the United States government. Their lands were opened to settlement by Americans, Canadians, and Europeans. The Northern Pacific Railroad reached the Little Missouri River in the fall of 1880. The Great Northern Railroad reached Williston in the early 1890s. Rails carried horses, beef, and other ranch products to eastern and Midwest urban markets. Among early badlands ranchers were Antoine de Vallombrosa, the Marquis de Mores, who bought cattle trailed up from Texas and turned them out on the open range, and future U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt. Both lost most of their herds during the very bad winter of 1886-1887. The Marquis’ poor business practices led to the closing of his beef slaughtering plant at Medora. Other ranchers, however, stayed in business because they managed their herds and crops with an eye to Dakota’s irregular weather, and erratic national markets. Complete the following task using the sources provided to build a context of the time period and topic being examined.

Formative Performance Task 2

Study sources A-C. Write a summary that answers the following questions: What types of sources are they (letters, photos, maps, diaries, etc.)? What is going on in these sources (what kind of information do they contain? Who created each of these sources? Who was the intended audience for each source? Why were these sources created? When were the sources created? What do the sources tell us about farming during the late 1800s? How do we know? What else can you find?

Featured Sources 2

The sources featured in this section are all primary sources. The letters were written by Louis Connolly to his wife, Mary (featured source A). Connolly came to Dakota Territory about the same time as Roosevelt and de Mores. He was born in Dundee, New York in 1846. Like many other families of the mid-nineteenth century, the Connolly family moved often, always aiming farther west and ending up in Henderson, MN. At nineteen, Louis Connolly went to northern Dakota Territory as a member of the 3rd Illinois Cavalry. After army service, he worked as a railroad surveyor until 1879. By that time, he was very familiar with Dakota Territory and decided to bring his family to the Bismarck area to live. He purchased land from the public domain at a low price (a preemption claim) three and one-half miles east of Bismarck on Apple Creek. He sold this ranch in 1881 for the very good price of $10 per acre and moved to what became Oliver County in 1884. There he established, with his father-in-law, the community of Hensler. Connolly was the mail carrier and had the post office in his home. Though reluctant to move, Connolly’s wife Mary and their three children, Celia, Florence, and Louis, Jr., joined him in Dakota Territory. When Louis and Mary retired from ranching in 1900, they sold 1200 acres of land along with livestock. They moved to Mandan where Louis served as mayor before he died in 1911. Mary Connolly lived until 1918. The letters can be found in the Louis Connolly Papers (SHSND Mss 20402).

The photo and autobiography (featured sources B and C) are related to badlands rancher, Arthur Clarke Huidekoper. A.C. Huidekoper came to northern Dakota Territory in 1881 to hunt and take a look at the badlands region. He was already well-established as a gentleman farmer of Pennsylvania who, as a descendant of a wealthy ancestor, had plenty of money and a comfortable life. In Dakota, he sought to enhance his livestock operations, and to also live the adventures of the West. Huidekoper joined the Eaton Brothers (also from Pennsylvania) in a beef operation near present day Medora. He bought enormous tracts of railroad land, which was available in a checkerboard pattern, leaving every other section in the public domain and open to homestead or timber culture claims. Huidekoper, though, thought these parts of Billings and Slope Counties would never be farmed, so he fenced huge portions of his land which also closed off access to legitimate claimants. Here he raised cattle until the disastrous winter storms of 1886-1887 destroyed most of his herd. However, he noticed that his horses had survived. He sold the remaining cattle and began to raise draft horses. The horses were shipped to his farm in Conneaut Lake, Pennsylvania for training, then were sold to large companies that needed heavy horses for pulling loaded wagons. Among his best customers was Fred Pabst, a Milwaukee brewer. For many years, there were few challenges to his claim, but in 1906, Huidekoper faced charges filed by the Department of the Interior which had ordered him to remove his fences and make the land he did not own available to homesteaders. Huidekoper spent a few days in jail, paid a fine, and in disgust with the inflexible system of land distribution, sold his ranch and horses. A. C. Huidekoper wrote several memoirs about ranching and his adventures in the badlands of North Dakota. Source B is from the Oral History Project Photograph Collection 00032. Source C is an excerpt from A. C. Huidekoper, My Experience and Investment in the Bad Lands of Dakota and Some of the Men I Met There (Baltimore: Wirth Brothers, 1947), 32-33.

| Source A |

Louis Connolly Letters: June 28; July 14; August 12 and August 24

http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/3155 |

| Source B |

Arthur Huidekoper Photograph

Arthur Clarke Huidekoper sits in the middle of the front row(third from left) of this undated photo taken on a ranch in Slope County. The other men are his partners and cowhands, and neighbors. |

| Source C |

Huidekoper’s Memoir The winter of 1886-87 was known as the hard winter. The summer of 1886 was so hot that the grass withered. The big herds came in late in the season in poor condition. That winter there was a great loss. The Ox outfit were said to have lost $250,000. I decided to gather my cattle at the next round-up and see where I stood. I suggested that we small outfits like Lang, Rumsey, Roosevelt, and others, do the same. Some of the outfits refused on account of the extra expense; others because they did not want to know; for if the tally was bad, they were afraid their backers would quit them. I was really the only man on the river who knew where he stood. We had about the same number of cattle as when we had started. We had years of hard work, for no profit. So I decided to go out of the cattle business, but I liked the life, and I found out that while the loss of cattle was large, there had been practically little or no loss in horses; so I decided to start a horse ranch. The name of the horse ranch was the Little Missouri Horse Company. The brand HT. I think the brand was selected from H representing Huidekoper, and T for Tarbell, who was superintendent. It was the best of brands, because it had straight lines, and a bar under the HT showed that the horse had been sold. We used a small brand under the mane for our full bloods and thoroughbreds. The company was composed of A. C. Huidekoper, Alfred H. Bond, G. Gorham Bond, and Henry Tarbell, originally; afterwards Earle C. and Albert R. Huidekoper and George F. Woodmen had interests. The ranch was located on Deep Creek, about 8 miles north of the Little Missouri River and the Logging camp. There were two very good springs on the place, one strongly impregnated with iron. We had a well impregnated with sulphur, which the horses liked especially. Gorham Bond and Pete Pelissier hauled one of the barns I had bought for the Custer Trail Ranch to the HT and had it erected. It was 100 feet long and 40 wide, with a good hay loft, some box stalls and some single [stalls]. To this was added a log bunk house and chicken house and wagon shed, also a small house for the foreman. In after years was added "Shackford", or the headquarters, and also a stable for a Bar Harbor buckboard, also kennels for a pack of hounds. In later years on my own account I had bought the railroad lands in Townships 134, 135, and 136, Range 102; also railroad lands in 134, 135, and 136, Range 103 and East half of Township 136, Range 104, in all 63,360 acres of land. Then we leased the school sections in these Townships, which gave us about 5,000 acres in addition to use. Shackford was built on a side hill, so that the basement was exposed entirely on the east and partially on the north and south. The dining room, kitchen, and store rooms were in the basement. There was a porch on the east and south sides; the entrance to the living rooms was where the side hill came level with the porch; the basement walls were of stone, the rest of logs. The living quarters had a large general room, a big stone fireplace with little seats on both sides, a wide divan on two sides of the room; off the main room were three bed rooms and a bath. There was a stairway to the basement and also to the dormer attic, which was used as an overflow. It was cool in summer and warm in winter. It was the best ranch house in that country, and the best ranch. Anyone who has had a chase after timber wolves with the "red pack" as we called [our hounds], on a September day will, I think, agree with me that it was the best day's sport of his life. We commenced with high standards for our foundation stock. I imported 35 purebred Percheron mares from France and six stallions. I bought some pure-bred stallions from Mark Durham of Oakland, Illinois. In fact, we had as good stock as anyone in the States. We bought some Oregon mares to cross with our full blood sire. Sitting Bull's war ponies were captured on the Canadian border and offered for sale. I bought some of these to cross on my thoroughbred stallion. Some of these ponies had bullet holes through their necks, received in the Custer fight. All in all, we bred up a splendid herd which numbered about 4.000 head when we sold it, and of course we sold many horses every year. I think we branded 1,000 colts the year that we sold. We bred full bloods that weighed a ton on the range. Some of our ponies sired by “Grey Wolf,” [with Indian mares as dams], worked for a few years with the herd and were sold for polo ponies and brought good prices. One sold for $1,500 and one for $2,500. The breeding up of this herd was a most interesting problem. With the exception of some full-blood stallions, the rest of the herd ran at large. We had three pastures fenced, containing about eight square miles each. In one of these were kept the full-blood mares, who were bred on the halter and their colts registered. After the full-blood mares were in foal, full-blooded stallion was turned into the pasture to catch any mare that came around again. The ranch work commenced with the spring round-up. The country was ridden for 100 miles square, or more. We had out-lying camps known as the "Spear" and the "Buffalo Spring" ranches. The colts were branded and tallied. Then some 50 mares were selected and a stallion selected that we thought would improve the conformation of the breeding. This stallion and his harem were put in charge of a cowboy, and for a week were herded by day and corraled at night. At the end of a week, the stallion would know his mares. He would not allow them to go beyond his sight, except when they were foaling. He would take them to some location favored by him, and there you would find him with his herd during the breeding season; after the breeding season they might separate into smaller bunches. A good [stallion] herder will watch his harem as carefully as a man herder could do it. He will fight for his family if another stallion challenged; and the fighting of the two stallions is something fierce. The defeated horse runs after his herd and tries to get them away before the victor captures them. Our thoroughbred stallion was very particular. If he did not fancy a mare, he would not have her in his harem. After the different stallions were located with their herds, it was almost as easy to find a herd as to find a man in the directory. You might have to ride fifty miles, but you would find him at his selected spot.... I had spent so much money on my importation that I felt very solicitous for their welfare in the winter. These imported mares lived on the range winter and summer and fed themselves. In winter they would bunch together in the Scoria Hills, and did not seem to mind the cold. I have seen the colts running around playing, with the thermometer 40 below zero. The mares looked the worst in early spring before the new grass came. At that time they would be sucking a great big last year's foal and nourishing another soon to arrive. At such times some of the mares looked thin, but they picked up wonderfully on new grass and were so fat by fall that they could hardly waddle. I spent fifteen years in breeding up the finest range herd in this country. Our ranch houses, our range, and our outfit were looked upon as the best. |

| Source D |

Learn more about the history of farming in North Dakota by visiting the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum or the Chateau de Mores State Historic Site.