The third supporting question, “how does your community make a decision?” helps students use sources as evidence to guide decision making. Historians have the advantage of hindsight. They know how decisions were made and can evaluate whether the outcome served its purpose well or not. In 1930 the state capitol burned down. Leaders had to resolve the problem of building a new building during a difficult economic time. Consider the data included in the featured sources and student’s knowledge of the capitol today to complete the following task. Use the sources provided to examine the problem and recommend a solution.

Formative Performance Task 3

Study the featured sources A-I. Imagine that your town or county was discussing building a new courthouse, school, or other public building. Public buildings are costly and often require imposing new taxes.

- What should your county/town do?

- Is a new building the best solution?

- What about remodeling or adding on to an existing building?

- What advice would you give the decision makers in your community?

- Was the new capitol a good solution to the problem of an adequate state house for North Dakota?

Use the text and sources to answer the following questions:

- Who discovered the fire? When?

- Who first reported it? Why are there discrepancies in the sources?

- What was the cause of the fire? Why was it difficult to determine?

- Was the fire seen as a tragedy or opportunity? Why?

Labor violence is rare in North Dakota, but strikers attacked other workers at the capitol construction site.

- Was violence necessary to get state officials and contractors to pay attention to the demands of the unskilled workers?

- Did the workers have a just claim to higher wages?

- Is it possible that there were communist labor organizers in North Dakota in 1933?

- What evidence do you have to support your answer?

Featured Sources 3

The sources featured below are primary sources. They are the raw materials of history—original documents, personal records, photographs, maps, and other materials. Primary sources are the first evidence of what happened, what was thought, and what was said by people living through a moment in time. These sources are the evidence by which historians and other researchers build and defend their historical arguments, or thesis statements. When using primary sources in your lessons, invite students to use all their senses to observe, describe, and analyze the materials. What can they see, hear, feel, smell, and even taste? Draw on students’ knowledge to classify the sources into groups, to make connections between what they observe and what they already know, and to help them make logical claims about the materials that can be supported by evidence. Further research of materials and sources can either prove or disprove the students’ argument.

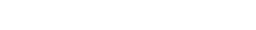

The First Capitol Building Burns Down

In 1883, the Dakota Territorial capital was moved from Yankton (now in South Dakota) to Bismarck. After North Dakota became a state in 1889, Bismarck continued to serve as the state’s capital. The original capitol building was constructed of dark brick. It was not as imposing as some state capitol buildings, but it sat on a hill with a view of the city and the Missouri River. The building housed state officials such as the Governor, Secretary of State, and the Attorney General as well as the chambers where the Senate and House of Representatives met. Each government office kept its records in fire-proof storage cabinets. While the old capitol building was in poor condition and had grown too small to continue to meet the needs of state government, it had been modernized with electrical wiring and city water. There was also a separate central heating plant located in a building just to the east of the main building. Each floor had two fire extinguishers, and the upper floors had fire hoses.

There are conflicting accounts regarding who first discovered and reported the fire in the old capitol building. One source says that early on Sunday morning, December 28, 1930, a janitor heard a loud cracking noise. Looking around, he found nothing, but when he went outside, he saw flames leaping from the Senate Chambers on the fourth floor. Though he called the fire department right away, the building was much too engulfed in flames to be saved. Another source says that a on December 28, 1930, the Day Guard, Joe Winkel, took over from the night watchman at 6:20 am. The night watchman had punched a clock at several points throughout the night as he made his rounds, ensuring that the building was under proper supervision at all hours. The night watchman had reported nothing suspicious or out of the ordinary. Just before 7:30, Winkel heard a sharp, cracking noise—perhaps a beam falling—signaling that something was wrong. Checking the fourth floor, he found the fire well underway. Winkel’s telephone call to the fire department at 7:30 am was answered by Bismarck’s three fire fighters and two fire trucks. Despite the 16-degree weather, citizens also came running or driving from their nearby homes. State officials turned out, including former Governor Walter Maddock, to help as they could. One fire truck, unable to drive up the icy hill, was pulled by people and their cars to the scene of the fire. [Resources: SHSND Series 30275; Series 30266; Larry Remele, ed. The North Dakota State Capitol: Architecture and History.]

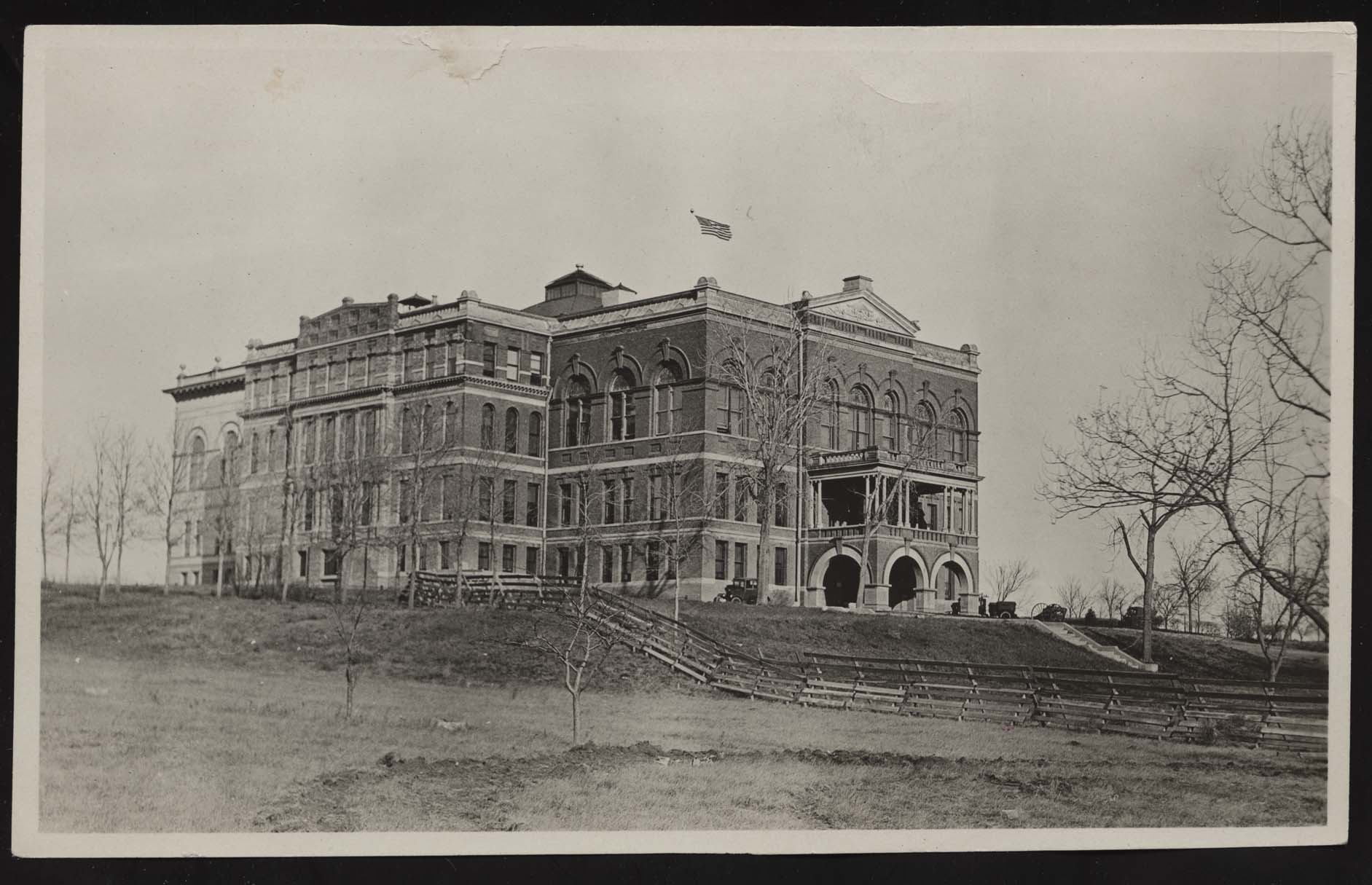

The Sanborn Fire Insurance map indicates that the capitol was served by a six-inch water pipe. There was also a 50,000-gallon reservoir. However, that still did not supply enough water to fight a fire that was already out of control before the first fire truck arrived. State officials who had been called to help save the building quickly turned instead to trying to rescue valuable documents. Secretary of State Robert Byrne found a ladder, climbed up to his first-floor window, and broke into his office. He handed important documents out the window to Charles Liessman, Assistant Secretary of State, who handed them down the ladder to his son, Emerson, and other citizens. The last document Secretary of State Byrne retrieved from the safe was the original North Dakota Constitution. Though some departments were able to save papers, others lost most of their records. Offices on the upper floors were destroyed by the fire and many records in the offices of the Highway Department, the Tax Commissioner, and the Attorney General where the vault exploded, were lost. The fire destroyed the entire building except for the two lower floors of the north wing.

While few people seemed upset about the loss of the original capitol, it was still important to try to determine the cause of the fire. There were many theories about what might have happened, including arson, but the two most probable causes focused on electrical wiring and spontaneous combustion. On Monday, December 29, the Bismarck Tribune reported on the statements of the State Engineer, R. E. Kennedy, whose office was on the top floor. Kennedy argued that the fire was caused by spontaneous combustion developing from turpentine and varnish-soaked rags left in the building by janitors who had recently cleaned and varnished legislators’ desks. Kennedy pointed out that the capitol had its own electric plant (in the maintenance buildings east of the capitol) which did not operate on weekends. Until 1929, janitors and guards used coal oil lamps at night and on weekends to light their work, but after lamps had previously nearly caused a fire, the capitol installed city electricity to power a few lights in the building after regular business hours. Because the main power source was not connected over the weekends, Kennedy stated that the source of the Sunday morning fire could not have been electrical. William Laist, the chief custodian of capitol buildings, argued against the spontaneous combustion theory. All rags used with oil, varnish, and turpentine had been removed from the building as soon as the refurbishing of the desks was complete. In addition, the night watchman regularly patrolled the building, clocking in at several stations at regular intervals to ensure adequate security. When the day guard on duty, Joe Winkel, heard a loud crack from the fourth floor, he passed the janitor’s closet on the way to check on the noise but did not see any smoke or fire there. When he got to the fourth floor, he found the fire was already well underway and working up to the attic. The watchman’s clocks could not be used as evidence for a detailed security routine because they had burned up in the fire. Assistant Fire Marshal Frank Barnes’ report appeared in the Bismarck Tribune on January 2, 1931. He sided with Kennedy. The cause he said, could not be determined with absolute certainty, but was most likely due to spontaneous combustion related to the varnish-soaked rags. He believed the night watchmen had not seen signs of a fire at the door of the janitor’s closet because the fire had possibly burned upward from the closet into the fourth floor.

The Fire Marshall’s report read:

“[a]s per your request I am herewith submitting a report of the investigation made of the capitol building fire which occurred Sunday morning, December 28, 1930, somewhere in the neighborhood of 8 o’clock. The investigation, so far, was made by Chief Assistant Fire Marshal Frank Barnes, who arrived at the scene of the fire about 30 minutes after the fire alarm was sounded. On his arrival at the premises of the fire it was impossible to ascertain just what cause this fire or the particular point where the fire originated. The fire was soon out of control and spread throughout the building very rapidly. The Bismarck fire department worked diligently in battling the flames but it was a losing battle from the start as the water pressure was inadequate and the fire had too much of a start. Mr. Joe Winkel, a janitor, who was alone in the building at the time the fire was first discovered and who turned in the alarm, states as follows: That he had been in the janitor room about an hour before he discovered the fire and was working in the Bank Examiner’s office on the ground floor which is located in the extreme southeast corner of the building and that about 8 o’clock he heard an unusual roaring noise in the building and left his work and went out of the office to ascertain what it was, but did not then discover the fire and returned to this work. In a few minutes he heard a loud noise resembling an explosion. He then went outside of the building and discovered smoke and flames coming through the southeast windows of the state licensing department offices, attached to the attorney general’s offices on the third floor, which were located right above the janitor room on the second floor. It is our belief that the noise heard resembling an explosion was caused by a falling beam or some other heavy object that had been burned loose by the fire. Our opinions and conclusion as to the origin of this fire, at this time with the meager information available and disclosed, are that the fire started in the janitors room on the second floor of the building about one-half hour or more before it was discovered and alarm sounded, cause of the fire being spontaneous combustion or some other unknown cause.”

Years later, Fire Chief Alvin Ode who worked in Bismarck’s Fire Department from 1948 to 1982, said that he believed the final determination was that the fire started in faulty wiring in the attic. Ode, as a twelve-year-old boy, was one of the first people on the scene of the fire. He entered the building at the request of Russell Reid, Director of the State Historical Society of North Dakota, to help retrieve portraits of former governors from offices in the southwest corner of the building. The cause of the fire was never determined with complete certainty.

| Source A |

North Dakota State Capitol Building (SHSND 0024-H-008) |

| Source B |

Sanborn Fire Map 1927

http://digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/3505 |

| Source C |

Corwin's Film of the Fire (1930) Duration 10:18 (minutes/seconds). Charles and Viola Liessman Papers, SHSND Mss 10113. |

| Source D |

Audio interview/oral history. Duration 35:51 (minutes/seconds) |

Building a New Capitol

Even before the fire burned it down, the first capitol building had become small and outdated. The governor at the time, George F. Shafer, had already planned to ask the legislature for an appropriation to replace the building with a newer structure that could better accommodate a modern government with multiple agencies. Many people around the state, including newspaper editors, felt the fire was not a tragedy as much as it was an opportunity to build a new capitol. They also noted for local authorities the necessity of safeguarding important city and county documents from fire. However, a new building, especially in the years of the Great Depression, would cost a great deal of money and the state was not wealthy. State leaders believed the citizens of North Dakota would not want an extravagant capitol built that could be perceived as wasteful spending. The combination of need and modest resources resulted in a building that drew on one of the newest architectural styles of its day, Art Deco, while responding to the needs of North Dakota’s citizens for a building that was practical as well as beautiful.

The 1931 legislature appropriated $2,000,000 to build a new capitol. This was a relatively small amount for a large public building. In comparison, Louisiana had recently appropriated funds for a new capitol that would cost more than $4,000,000, and Nebraska was building a new capitol which would cost $10,000,000 when completed in 1932. To plan a building adequate for state offices that was also fire-proof and elegant enough to suggest the power and dignity of the state for such a small sum was a bold move, but also reflective of North Dakota’s values, the economic depression that had dogged the state since 1920, and the international architectural movement toward spare and functional styles.

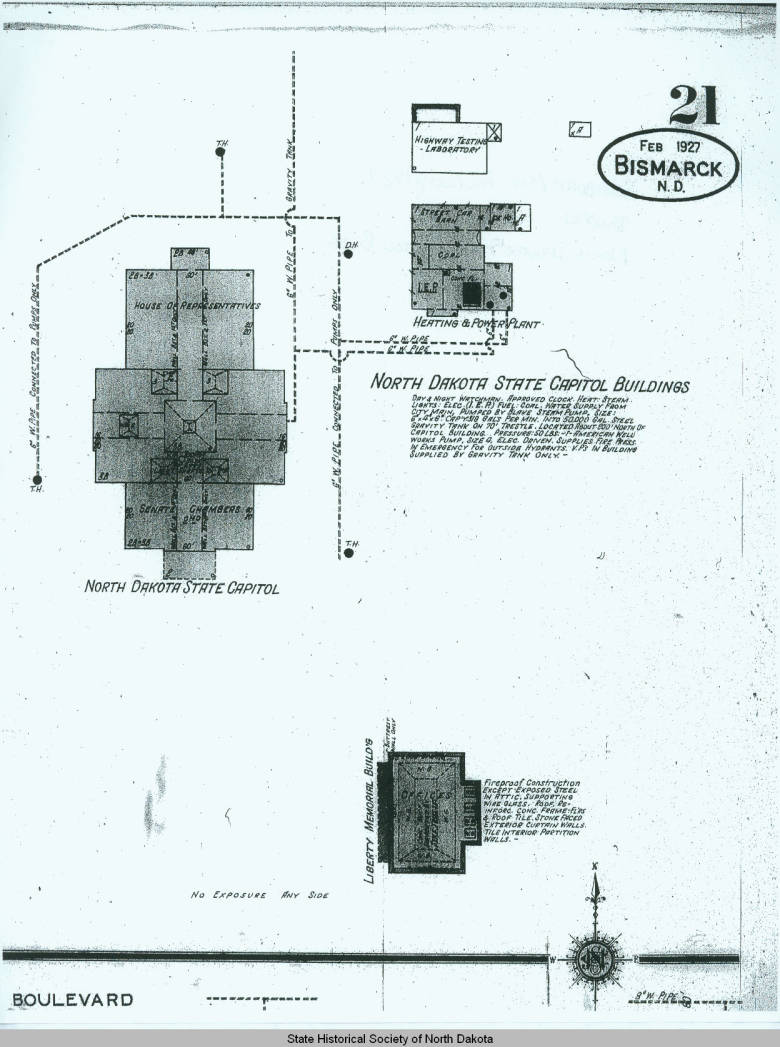

After a painstaking search, the Capitol Commission settled on the well-known Chicago architectural firm of Holabird and Root. The legislature had specifically requested that the building use North Dakota materials and North Dakota contractors when possible. In order to meet that constraint, the commission hired Holabird and Root to design of the building, but also hired two of North Dakota’s premier architects, Joseph Bell DeRemer of Grand Forks and William Kurke of Fargo, as the on-site architect and construction superintendents. North Dakota has few quarries for marble, granite, limestone, or the other building materials chosen by the architects to cover the steel beam framework, and few North Dakota contractors had experience with high-rise buildings, so contractors and much of the material came from other states.

| Source E |

Andreas Risem Photography Studio: Official Photos of Capitol Construction

Construction of the New Capitol. SHSND: C3322. When construction began on the new capitol building, the Capitol Commission hired a Bismarck photographer to record the construction process. Andreas Risem, who owned a photography shop in Bismarck for thirty-three years, took more than 700 photographs of the construction and other activities on the capitol grounds including the strike of unskilled laborers. Risem, who had been born in Norway in 1875, recalled that the work of photographing the capitol was his most difficult assignment. The contractor, Lundoff and Bicknell, was headquartered in Ohio, and wanted photographs which showed how difficult it was to build in a North Dakota winter. Risem set out to shoot on a winter day with the temperature at twenty below zero and the winds blowing at 30 miles per hour. The bulb release on the camera froze and he had to trip the shutter with the lever. At the end of the day, he was exhausted from the effort in the intense cold. The result, however, is an extremely important historical record of construction, of human, machine, and animal labor, and of discord over wages. Through his photographs we can see the skeleton of steel which holds up the skyscraper, and the process of lining the steel with limestone. |

| Source F |

Memorial Hall in the North Dakota State Capitol

|

The Strike

Approximately two hundred men worked daily on the capitol building. Some were skilled stone masons, iron workers, or carpenters; while others were unskilled laborers who lifted, hauled, pushed, pulled, and did anything the boss told them to do. They were the lowest paid and had the least ability to find other work if they were laid off or quit. The wages of the unskilled laborers were the lowest on the construction site. Bricklayers and stone masons earned the highest wage of $1.10. Other skilled workers earned between eighty cents and one dollar per hour. Rough carpenters earned seventy cents per hour. From there the wage scale dropped to thirty cents for “Common Laborers.” On May 16, 1933, after more than ten months on the job, the unskilled laborers walked out on strike. At 4:30 in the morning, picketers stood in front of the Liberty Memorial Building to prevent other workers (those not on strike) from entering the capitol construction area. Striking unskilled laborers asked for a raise in their hourly wage from thirty cents to fifty cents.

Approximately two hundred men worked daily on the capitol building. Some were skilled stone masons, iron workers, or carpenters; while others were unskilled laborers who lifted, hauled, pushed, pulled, and did anything the boss told them to do. They were the lowest paid and had the least ability to find other work if they were laid off or quit. The wages of the unskilled laborers were the lowest on the construction site. Bricklayers and stone masons earned the highest wage of $1.10. Other skilled workers earned between eighty cents and one dollar per hour. Rough carpenters earned seventy cents per hour. From there the wage scale dropped to thirty cents for “Common Laborers.” On May 16, 1933, after more than ten months on the job, the unskilled laborers walked out on strike. At 4:30 in the morning, picketers stood in front of the Liberty Memorial Building to prevent other workers (those not on strike) from entering the capitol construction area. Striking unskilled laborers asked for a raise in their hourly wage from thirty cents to fifty cents.

| Source G |

The Strike These documents are drawn from the Memorandum of Daily Progress given to the members of the Capitol Commission who oversaw construction. Look for headings “Labor Strike,” “Labor Situation” on these pages. In addition, look at photographs taken by Andreas Risem of the strike. Source: SHSND Memorandum of Daily Procedures, Series 30275.

In February 1933, common laborers pour cement on the capitol roof. SHSND: 0012-060.

Strikers picket capitol grounds. May 1933. SHSND: 0012-081.

These National Guard officers patrolled the capitol grounds during the strike. Adjutant General Herman Brocopp stands at left. 30275 Box 1 book 8 Memo 06-06-1933-1.

Strikers gather in front of the capitol to discuss their situation. SHSND: 0200-5x7-0223.

Strikers attack a delivery truck on May 24. Several men were injured, and strikers were jailed. 30275 Box 1 Book 8 Memo 06-06-1933-06.

Photographer Andreas Risem identified the speaker addressing this group of strikers as a communist. 30275 box 1 Book 8 Memo 06-06-1933-11.

Strikers are notified of a settlement and all workers are anxious to resume work on the building. 30275 Box 1 Book 8 Memo 06-06-1933-07. |

Cornerstones

Most important buildings have a cornerstone which contains a box full of items representing significant people and events from the date of construction. Both the 1883 capitol and the 1934 capitol had cornerstones inserted in the beginning of construction and the event was cause for celebration. In 1883, the laying of the cornerstone coincided with the arrival of a special train carrying former president Ulysses S. Grant, Henry Villard, president of the Northern Pacific Railway, and other important gentlemen to the ceremony celebrating the completion of the Northern Pacific in the state of Washington. For forty-five minutes, these men and local dignitaries, including Sitting Bull and Dakota Territory Governor Nehemiah G. Ordway, made speeches about the great future of the territory and the railroad. Anyone present was invited to throw a small card with their name on it into the copper box which would be placed in the cornerstone. In addition, newspapers, coins, and the program of the day were placed in the box. Native Americans attending the ceremony placed beads, rings, and pieces of cloth as remembrances of their participation in the ceremony.

In 1931, after fire destroyed the first capitol, the copper cornerstone box was opened, and the contents were turned over to the State Historical Society of North Dakota. At the same time, plans were being made to place another copper box in a cornerstone of the new capitol. The date was set for October 8, 1932. Governor Shafer declared it a state holiday. Vice President Charles Curtis, the first Native American (Kaw) to hold that high office, attended in place of President Hoover. The copper box was 12.5 inches by 23.75 inches and 15.75 inches high. The contents included the Governor’s and Vice President’s speeches, newspapers, state documents, and photographs of former governors, legislators, and capitol custodian William Laist. Governor Shafer recognized the importance of the new capitol as a symbol of the modern era. He said:

“As we look upon these scenes today, we are keenly conscious of the definite passing of the pioneer period in the development of North Dakota and the Northwest. While there are some among who personally witnessed, and other who actually assisted in the locating and building of our first state House on these grounds, and whose presence here this day is a delight and inspiration to us all, yet we know we have entered another era in our history and that soon all touch with pioneer past will be but a memory, found only in the records of yesterday.”

Perhaps concerned that the modern design of the building would offend more traditional citizens, Shafer also offered his interpretation of the architecture:

“...it will offer an imposing salute to the grandeur of the past in a form of such imposing dignity as to challenge the respect and inspire the reverence of every person who gazes on its classic form. In its qualities of efficient utility and elements of modern convenience, it is believed to be the superior of any public building in America, and for absence of extravagance and maximum economy of space and use, its design will ever remain a brilliant tribute to the artistic skill of the architects who conceived it and to this efficiency of the artisans and engineers who constructed it.”

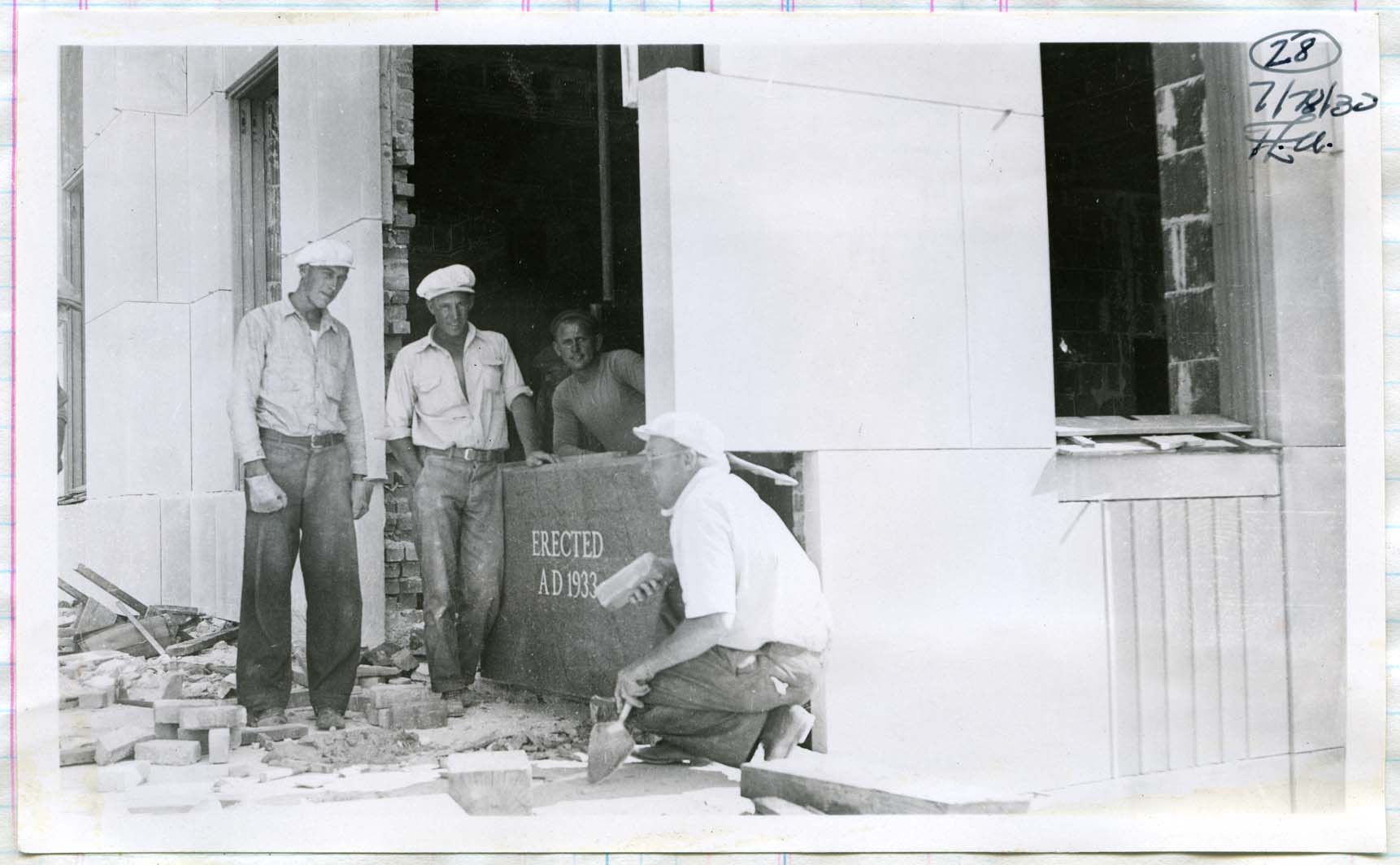

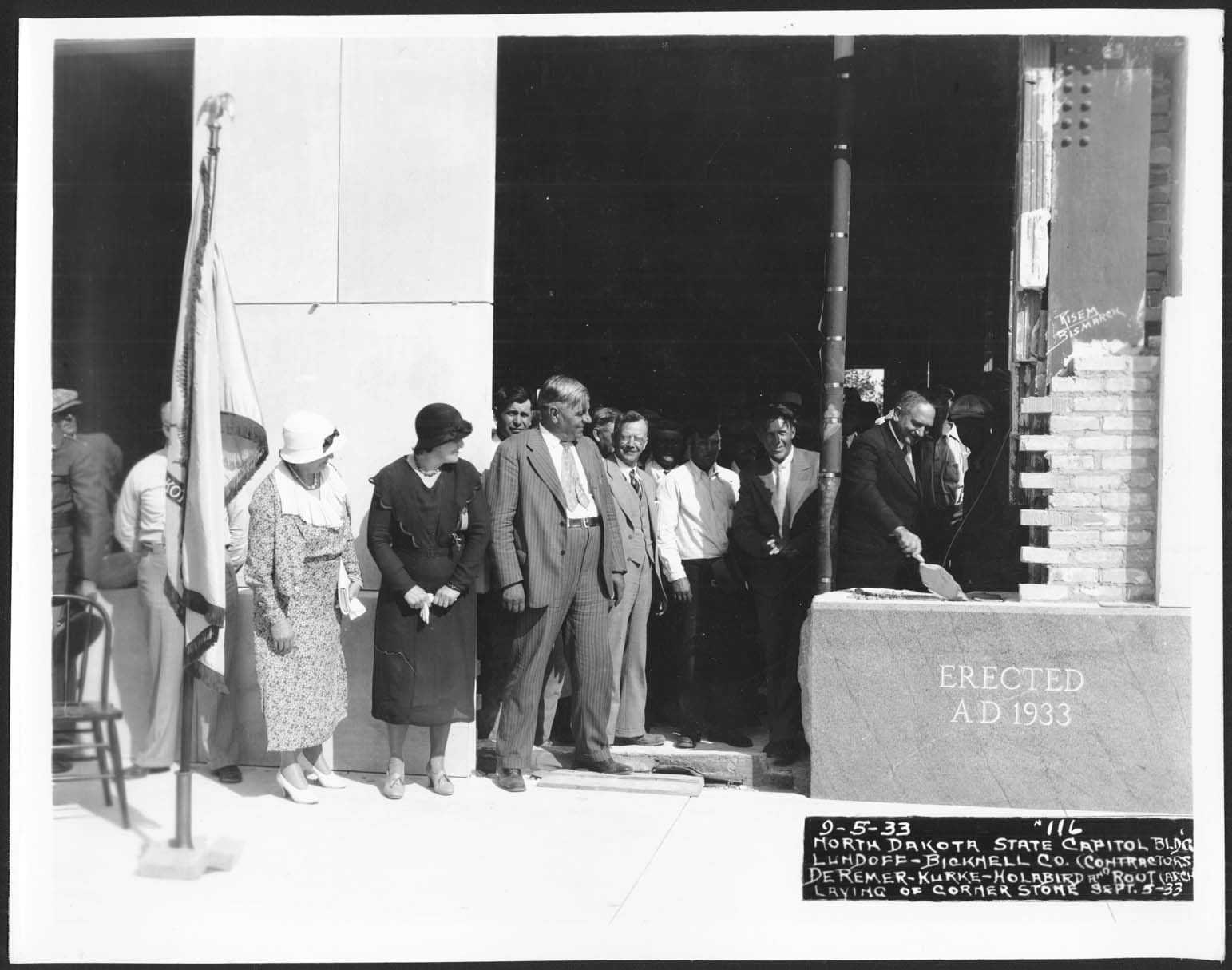

This cornerstone did not last long. It was vandalized (the box was not damaged) and had to be replaced in 1933. This time, in a much-abbreviated ceremony, Governor Langer dedicated the cornerstone on the fiftieth anniversary of the dedication of the territorial capitol cornerstone. Stone mason Hynek Rybnicek of Mandan selected the stone from a Morton County field and cut it to the exact shape. Rybnicek remembered this as a particularly difficult job because the new cornerstone had to fit into a space in a building that was nearly half completed.

Today the cornerstone and its contents remain in place in the capitol foundation. At some time in the future, the contents will be opened to reveal a little bit about the people who saw the skyscraper capitol rise during the Great Depression.

| Source H |

Contents of Corner Stone Receptacle

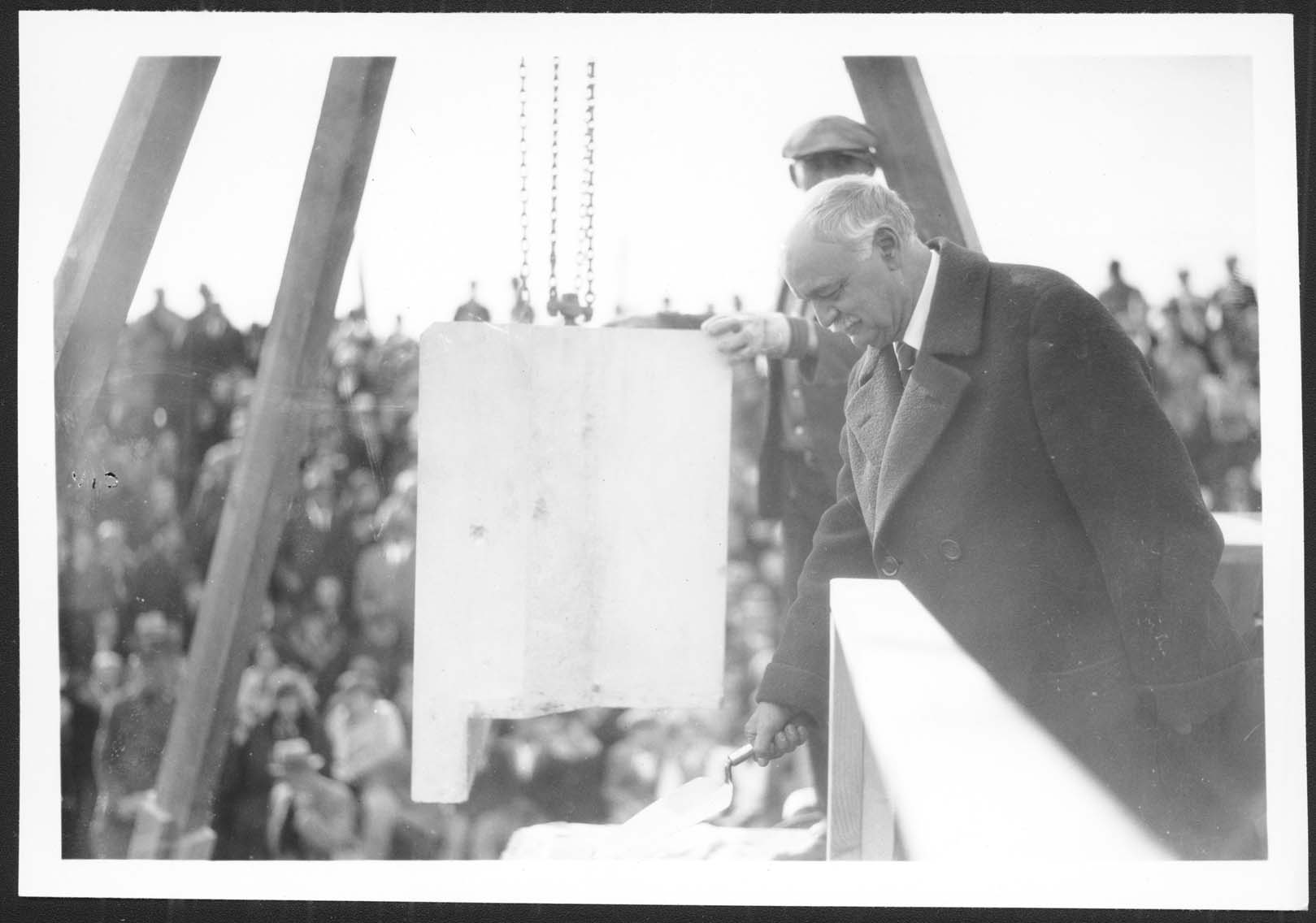

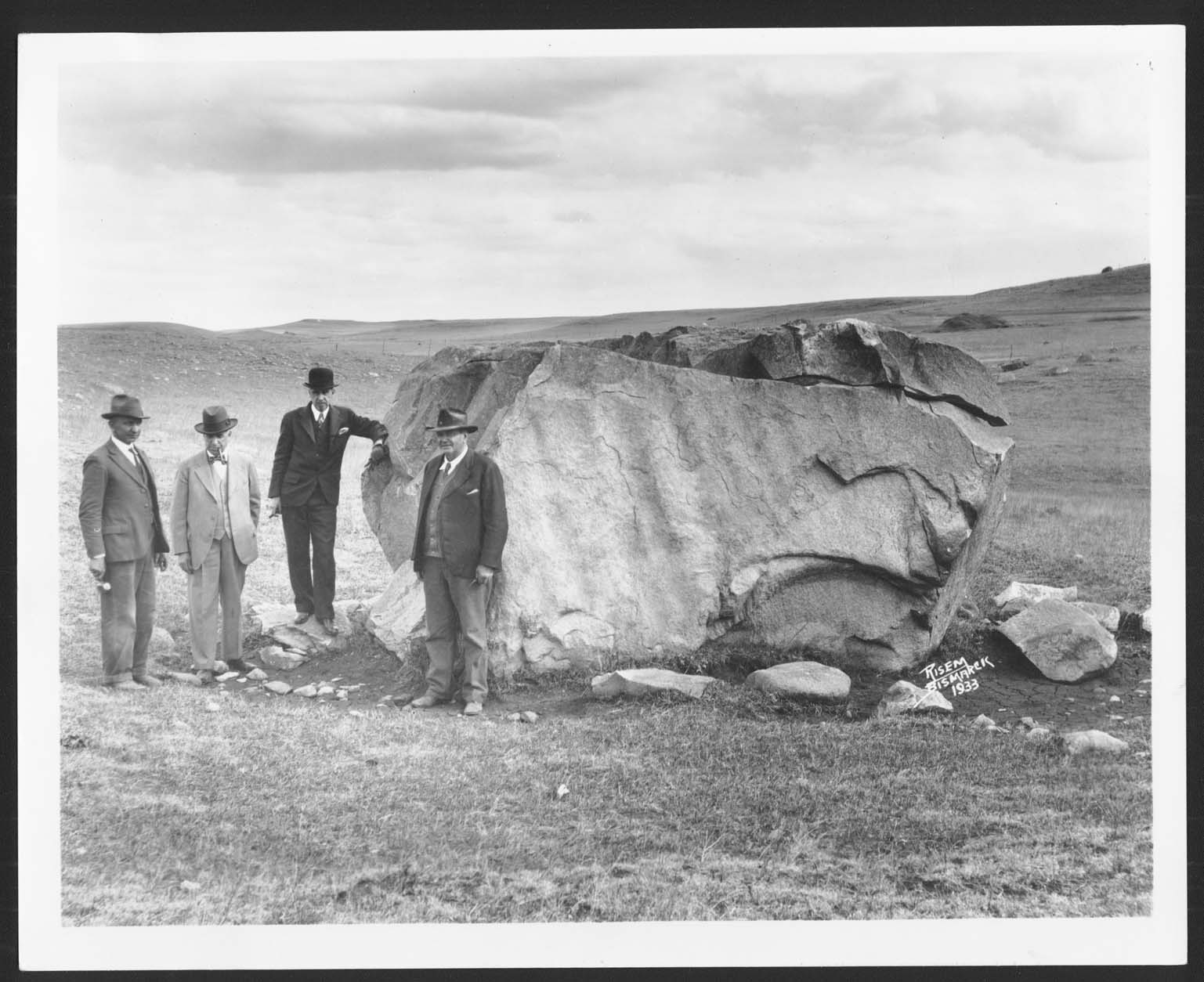

Vice President Charles Curtis places mortar under the cornerstone on October 8, 1932. SHSND: A6853-1.   Stone mason Hynek Rybnicek, architect Joseph Bell DeRemer, capitol commissioner Ernst Warner, and capitol grounds man Dobson, spent a day east of St. Anthony in rural Morton County looking for the perfect stone from which Rybnicek would carve the 1933 cornerstone. They selected the stone upon which they stand. First image: Second Image:

Workmen set the new cornerstone in place before the dedication ceremony. 30275 Box 1 Book 8 Memo 7-29-1933-28.

Governor William Langer applies mortar to the new cornerstone September 5, 1933. SHSND: 0012-116. |

| Source H |

Telegram The following transcription is from a telegram sent by President Hoover: The White House, Washington D.C. Oct 8th 1932 Governor, Bismarck N.D. I most heartily congratulate the people of North Dakota upon the laying of the corner stone of the new state capitol this afternoon it is not only a symbol of the enduring foundation of self-government which underlie the security of America Life it is also a symbol of the indomitable courage of the people who are never daunted by disaster but build anew with energy and faith. Herbert Hoover, 1245pm. |