In 1954, the United States Supreme Court handed down a decision in the case of Brown vs. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. The decision, sometimes simply called Brown, declared that public schools had to admit children of all races. Schools could not be segregatedSegregation means that schools, theaters, stores, and other public spaces are divided by race. For instance, before <em>Brown vs. the Board of Education</em>, African American children attended different schools than white children attended. Movie theaters usually allowed African Americans to sit only in the balcony. Though segregation existed by law and custom in southern states, it also existed in northern states, especially in the schools.

Integration means that people of different races are allowed, or encouraged, to enter the same schools, stores, restaurants and other places together. School integration means that black and white children attend the same schools.

Desegregation is the process of changing from a segregated institution to an integrated institution. by race. School districts all over the country began to make arrangements to open the schools to all children. However, many school districts in southern states looked for ways to resist integration of the schools.

Brown was an extremely important Supreme Court decision. The decision changed culture and traditions that had been in place for over 100 years. In addition, Brown overturned an earlier court decision that had established segregation as the law of the land. In that decision, Plessy vs. Ferguson (1896), the justices of the Supreme Court had said that segregation was acceptable in schools, restaurants, trains, and other places as long as the accommodations were equal. The phrase, “separate but equal,” comes from that decision. Unfortunately, schools were segregated, but not at all equal. Schools for black children lacked books for each child, decent school rooms, indoor bathrooms, and adequate playground equipment. Black teachers were dedicated, but they had few of the teaching materials they needed to teach well.

In Little Rock, Arkansas, the school board made plans to integrate elementary schools. Parents, however, did not want integration to begin in elementary classrooms. The school district then planned to integrate the high schools very gradually. Only a few black students would be admitted at first. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) tried to get Little Rock schools to integrate more quickly, but the federal courts said that gradual integration was acceptable.

In August, 1957, the Mothers’ League of Central High School petitioned the school to prevent the enrollment of black students. The Mothers’ League argued that integration would lead to violence. The school district agreed and suspended plans to integrate the school.

The integration issue was brought to the federal district court. Judge Davies of the North Dakota District federal court (in Fargo) had been sent to the Arkansas federal courts to help temporarily with the work load. Judge Davies declared that the school district must continue with its plan for integration.

The first day of classes was scheduled for September 3, 1957. On September 2, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus asked the Arkansas National Guard to keep order at the school. The school board asked the black students who had registered to not attend the first day of school. Judge Davies, once again, ordered the school district to proceed with integration. (See Document 1.)

On September 4, nine African American high school studentsThe nine students were Minnijean Brown, Terrence Roberts, Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, Jefferson Thomas, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Thelma Mothershed, Melba Pattillo Beals. attempted to enter Little Rock Central High School. They were turned away by National Guard troops. One girl, Elizabeth Eckford, approached the school from a different direction than the other eight black students. All alone, she faced an angry group of white people. With dignity and courage, she made her way to a bus stop where she was able to board a bus to take her home.

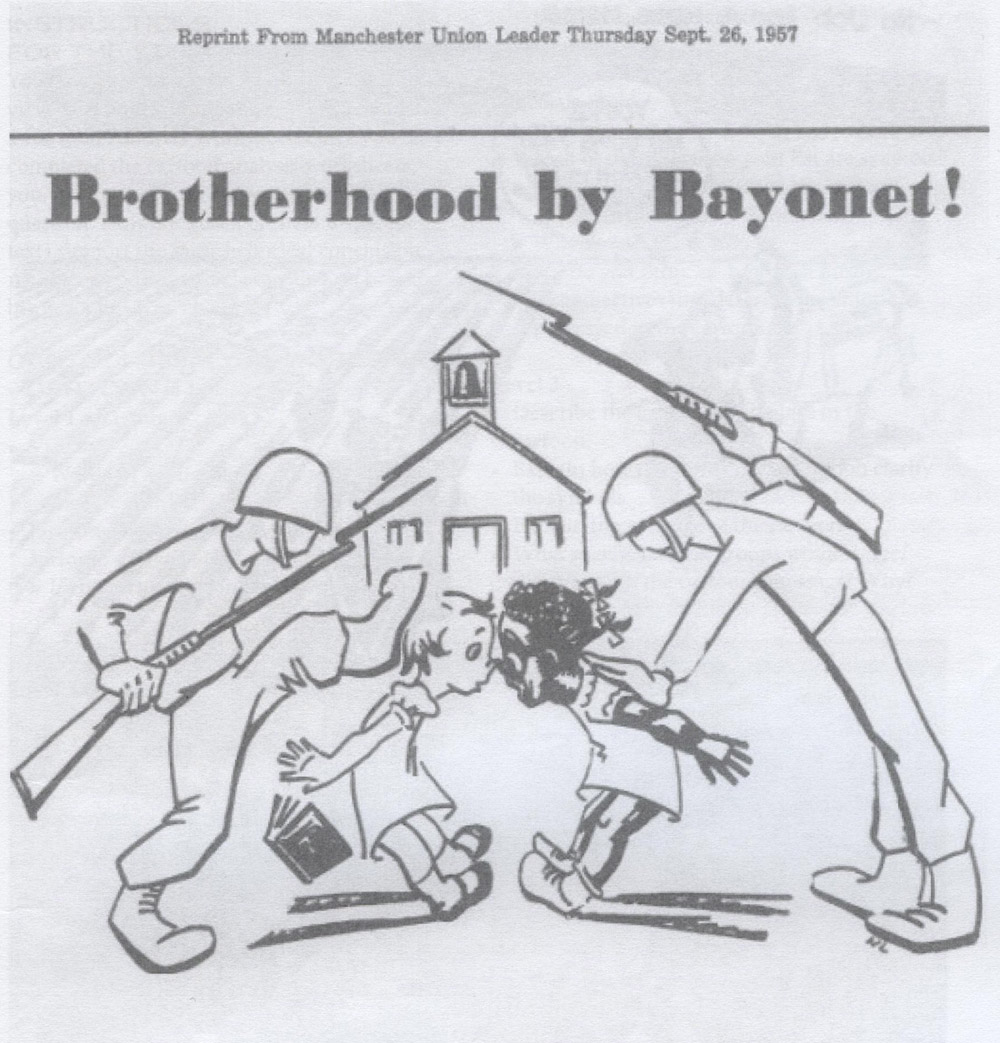

Twice more, Judge Davies ordered the school district to admit the students. (See Image 1.) School and state officials delayed. On September 23, the nine students, known as the Little Rock Nine, quietly entered the school while the unruly crowd outside the school turned their attention to four African American reporters. (See Image 2.) With violence in the streets, Little Rock Mayor Mann asked for federal assistance. President Eisenhower sent the Army’s 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock and nationalized the Arkansas National Guard. The nine students entered school under the protection of federal troops.

By the end of October, the crowds had left the school grounds, but the African American students endured daily abuse in school. More than 100 white students were suspended for violence; one black student was suspended for retaliating to violence. However, the other eight students remained in class. Ernest Green, the only senior, graduated in May, 1958.

The following school year, Little Rock high schools were closed. Integrated Little Rock high schools re-opened in 1959.

Why is this important? The integration of schools throughout the United States brought great cultural and social changes to towns and cities. The changes would not have occurred without the steady commitment of judges and elected leaders. While elected leaders such as Governor Faubus have to respond to the people who elect them, federal judges are appointed by the president of the United States and approved by Congress. Judges uphold the law and the constitution without regard to their personal feelings.