In the early 1930s, many North Dakota students lived in remote, rural areas far away from a high school. During that time, only about 50 percent of students graduated from high school. It was also a time when many parents could not afford to send their children to high school and for many, formal education often ended after 8th grade.

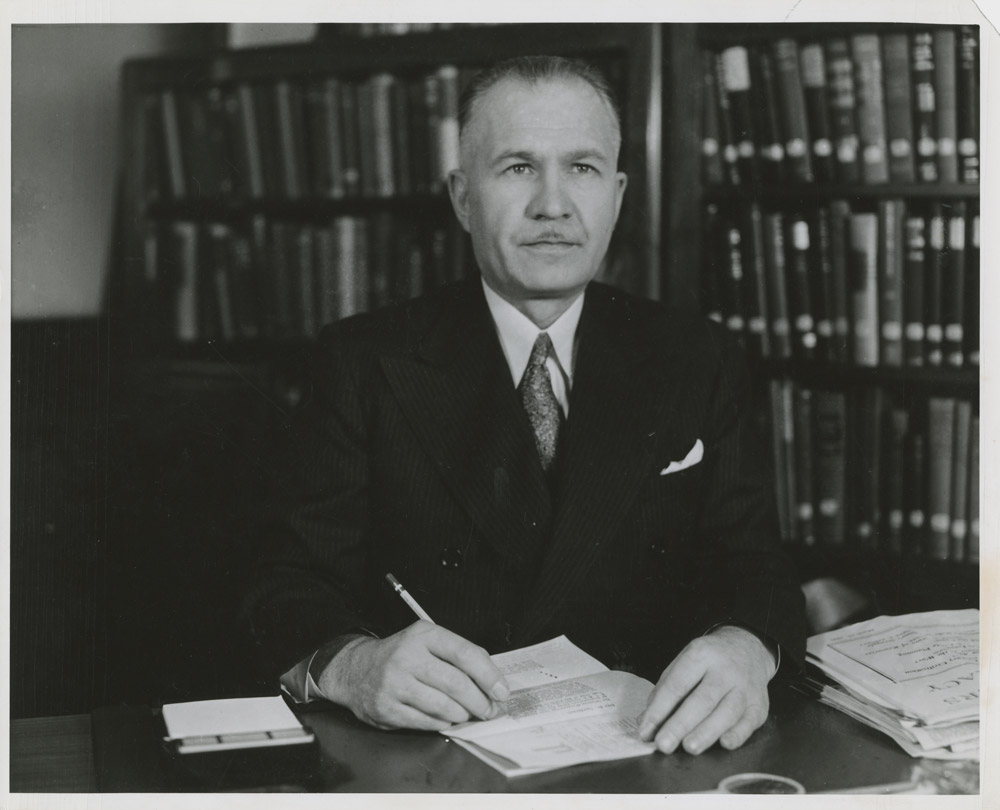

Dr. T. W. ThordarsonDr. Thordarson knew from personal experience that students in remote rural areas of North Dakota might have trouble getting a good education. He was born to an Icelandic immigrant family and spoke little English when he entered first grade. However, he had already read Shakespeare, Ivanhoe, Oliver Twist and other classics in Icelandic. He attended school three months in the fall and three months in the spring. As a 10 year old, Thordarson had to help with farm work. He quickly decided that farming was not for him, but it was difficult to get more education. He attended high school classes whenever he could and worked the harvest pitching bundles of wheat to the threshers to earn the money to pay for his education. He eventually graduated from Valley City Normal School (Valley City State University), North Dakota Agricultural College (B.S. and M.S.), and a law degree (which he earned through correspondence study). had an idea to fix the problem. (See Image 1.) He wanted to start a correspondence high school. A correspondence school mails lessons to the students. The students complete their lessons and mail them back. Students take their tests under the supervision of a local teacher. Dr. Thordarson taught agricultural courses for the North Dakota Agricultural College (now NDSU) through a correspondence system. He was experienced in distance education and knew that there was a great need for a correspondence high school in North Dakota.

Lulu Evanson, a member of the Farmers Union, also knew about the need for correspondence courses. She brought the issue to the Farmers Union convention. When Dr. Thordarson learned that the Farmers Union shared his interest, he contacted the organization. He offered to write the bill to create a correspondence school if the Farmers Union would bring the bill to the legislature. The bill became law in 1935. North Dakota was the first state to create and fund a program of supervised correspondence study.

The Division of Correspondence Study was located on the North Dakota Agricultural College campus in Fargo. Dr. Thordarson became the first director of the school; eight part-time teachers developed courses and graded the students’ work.

The school was designed to meet the needs of students living on remote farms and in small towns. Over the years, the school has also enrolled students from larger high schools, every state in the United States, and several foreign countries. There are many reasons for students to enroll in correspondence study. (See Image 2.)

Originally called the Division of Correspondence Study, the school has had several names. From 1971 to 2007, the name was Division of Independent Study. Today it is known as the North Dakota Center for Distance Education. Students can choose from hundreds of different courses. Many courses are now offered through internet technology, but students still have to complete their tests under the supervision of a local teacher.

Dr. Thordarson continued in his role as director until 1968. His dedication to the Center never faded. He believed that distance education (correspondence study) provided “training better adapted to individual needs than the regimented curriculum [of the public school system.]” In 1940, Thordarson wrote in a national journal article that “the state of North Dakota operates a plan looking toward a diagnosis and a treatment of the vocational needs of youth, particularly those in small high schools.” Thordarson wanted the school to adapt to students’ needs, rather than students bending to the curriculum offered.

Today, the Center’s students might live far from a high school, be older than average, unable to enroll in local schools. Some students enroll in the Center’s courses when their local school or schedule does not allow them to take courses they want.

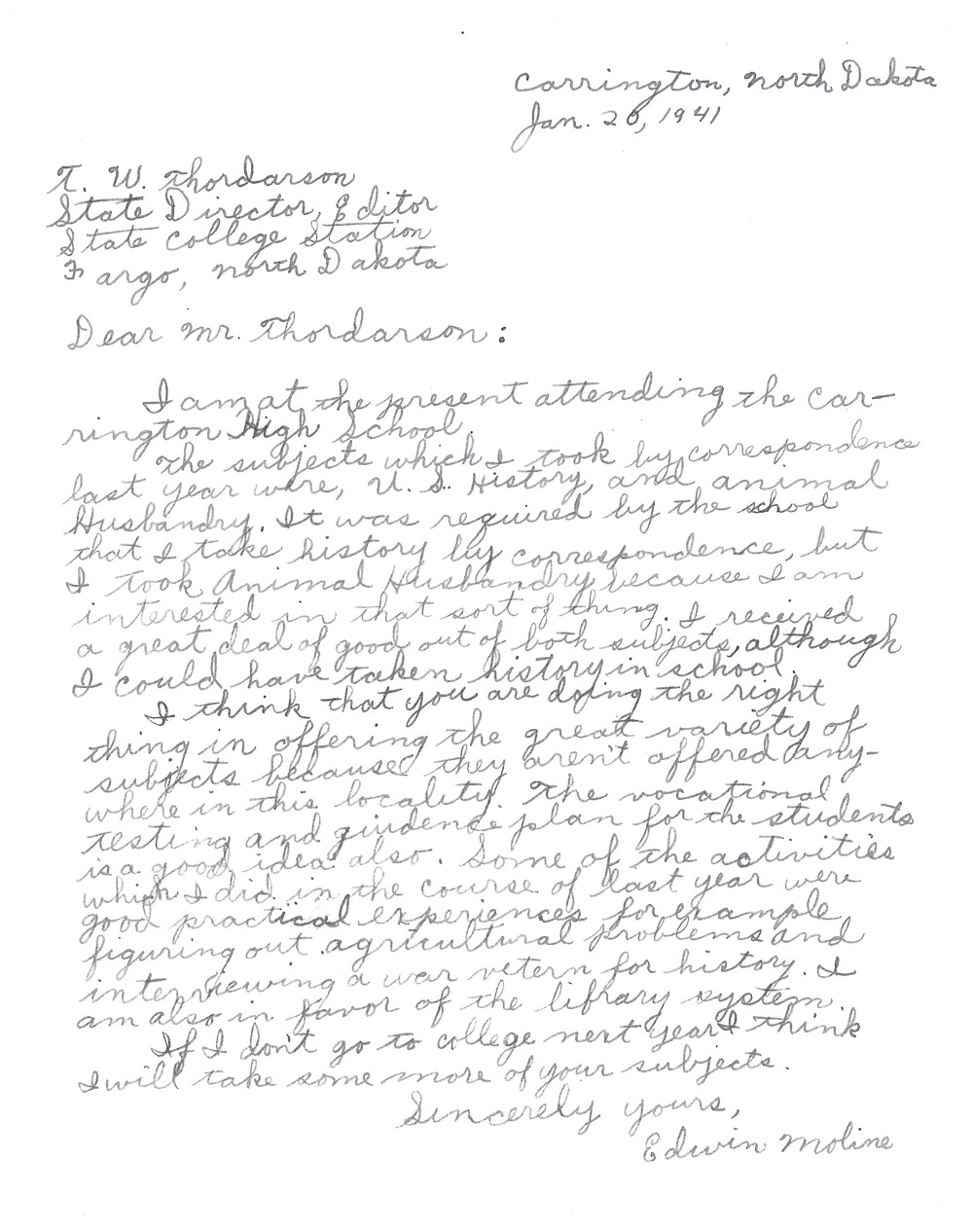

Students can take all of their high school courses or just a few courses through the Center. Beginning in 1944, graduation exercises have been held in Fargo. Many students travel across the state to participate in the commencement ceremony. Hundreds of students have graduated from the Center. (See Image 3.) Among the graduates is former Lieutenant Governor Lloyd Omdahl (class of ’49).

In 1985, the Center celebrated its 50th anniversary. By this time, the Center had its own building on the NDSU campus. Since its founding, thousands of students, including pop music star Bobby Vee,On February 3, 1959, sixteen-year-old Bobby Veline of Fargo stepped onto a Moorhead, Minnesota stage to replace rock star Buddy Holly who was killed in a plane crash on his way to Fargo for the show. That was the start of Bobby Vee’s career as a pop music star. His hits included “Devil or Angel,” “Rubber Ball,” and “Take Good Care of My Baby.” In 1999, Bobby Vee was named to the Theodore Roosevelt Rough Rider Hall of Fame. have completed courses. (See Image 4.) Students have ranged in age from gifted elementary students to mature adults who wanted extra educational opportunities.

Studying high school courses through distance education requires commitment and self-discipline. (See Document 1.) No one is taking attendance or reminding the students that their homework is due. On the other hand, students study when it is convenient and choose courses that they need or interest them. When they enroll in the North Dakota Center for Distance Education, students become part of North Dakota’s biggest high school.

Why is this important? The North Dakota Center for Distance Education (formerly the Division of Correspondence Study) is another example of how North Dakota identifies and solves its problems. People believed that a high school education was important and did not have to remain out of reach for rural students. Farmers Union provided the political leadership to the problem of rural education. Dr. Thordarson knew how to develop and run a correspondence school. The school succeeded because it met a real and on-going need. Dr. Thordarson’s idea of “equalizing educational opportunity for all” is true to the spirit of North Dakota.