In 1952, the federal government developed a new policy for American Indians. It was called the Urban Relocation Program. Under this new policy Indians were encouraged to leave the reservation and move to a city. The stated purpose of relocation was to encourage assimilation. Assimilation requires a person to give up the culture they lived in and accept another culture as their own. A person who is completely assimilated fits into the dominant culture. For American Indians this meant giving up tribal ties, the language of their community and family, and their place in a reservation community.

Some Indians had already been through a voluntary relocation process. Many had migrated to cities during World War II (1941 to 1945) where they found work in wartime industries. These were good jobs, but many of these jobs ended after the war when the plants shut down to prepare for peacetime production. Some Indians returned home at that time; others remained in the city. In addition, many American Indians served in the Armed Forces during the war.

While these young people were absent from their reservations, they were unable to participate in the ceremonies and other community events that helps everyone feel a part of the community. Some lost track of their relatives or did not know how to participate in the community when they returned home.

Though it was a voluntary program, there was a lot of pressure to leave the reservation. When the federal government offered help in finding jobs, housing, and schools in distant cities, many people agreed to go. Poverty on the reservations also motivated people to leave. The average annual income for white Americans in 1950 was $4,000. African Americans earned an average of $2,000. American Indians earned $950. Most American Indians did not live in cities, and there were few jobs on reservations.

The support systems promised to relocated people did not work well. Jobs were often not available, and American Indians experienced racial discrimination in cities. Federal agents did not help American Indians find homes in neighborhoods with other Indians. The point was that they were supposed to give up their traditional ways and adopt new ways to live. This isolation from everything that had once been important to them, caused many people to regret having left the reservations.

Some people stayed in the cities. They found jobs and homes and, though they felt disconnected, their children began to adapt. Eventually, native peoples began to organize community centers in these cities. Using their own interests as their guide, they overcame the isolation of city life and created a space where they could maintain their cultural ties and provide needed services.

American Indians of many tribes moved to Chicago under the relocation plan. In 1953, some relocated Indians organized a community center. Today, more than 60 years later, the American Indian Center of Chicago provides social services and a place where Indians feel comfortable and at home. Members direct and control the services and activities of the center. The American Indian Center calls itself “a brave experiment in community self-determination.”

In 1962, the federal government made some changes to the relocation program. The name changed to Employment Assistance and the program placed a new emphasis on skills training. Families could choose to relocate to cities near their home reservation so they could be close to their families. Cities such as Bismarck and Fargo, as well as nearly every county in North Dakota, have seen steady increases in the American Indian population since 1962.

Why is this important? Though the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) did not keep good records on relocation, it has been estimated that nearly 750,000 American Indians relocated between 1952 and 1980. By 1960, this number included 2,900 Chippewas in addition to people from the other reservations in North Dakota.

Relocation was not forced on the tribes, but for those who believed the promises, the outcome was often devastating. Many of the people who relocated felt the sorrow from loss of family and community. Without family support, many relocated Indians became poor, homeless, and lost hope. Others returned home if they could. Some came back to their reservations with skills that were useful on the reservation. Those who stayed in the cities found a way to build new communities there. Relocation, like termination, helped lead tribes to new ways to think about protecting their reservation homes and their cultures in spite of the huge obstacles they had to overcome.

Relocation of the Three Affiliated Tribes

A short time before Congress and the Bureau of Indian Affairs approved the Urban Relocation Program for Indian tribes, the Mandans, Arikaras, and Hidatsas of the Three Affiliated Tribes at Fort Berthold Reservation experienced a different relocation situation. Congress had approved the building of Garrison Dam on the Missouri River. When finished, the dam flooded 156,000 acres of the Fort Berthold reservation.

In 1945, life on the Fort Berthold Reservation was good. Though many of the younger men had been away at war (World War II, 1941-1945) for many years, agricultural production was growing. Divorce was rare, and most children lived in two-parent families. Less than three percent of the residents (mostly elderly or disabled) depended on federal financial assistance. All of the children were enrolled in school. The Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras lived on the land where their ancestors had lived for hundreds of years.

Though the tribes fought the legislation that took their traditional homelands and flooded several of their towns, work on the dam proceeded. (See Image 1.) Tribal chairmen Martin CrossMartin Cross led the fight to stop the dam. The federal government was not going to give up on the system of dams on the Missouri River. Even after losing the dam fight, Cross continued to fight to restore tribal rights to water and mineral resources as well as control of the tribes affairs. Cross was elected chair of the council, but he was also the son of a former tribal leader, Old Dog. Cross felt the pull of tradition and the pull of modern legal and financial demands. He is often described as a man standing between two worlds. and George Gillette made many trips to Washington, D.C. to speak to members of Congress and the Commissioners of Indian Affairs, but they could not stop dam construction. In 1953, as the flood waters rose on Lake Sakakawea, hundreds of families were relocated to newly built towns.

The relocation process had terrible consequences. Some families decided to leave the reservation. They left on their own or took advantage of the federal relocation program. Some left in despair of losing their homeland; others left because they faced an uncertain future.

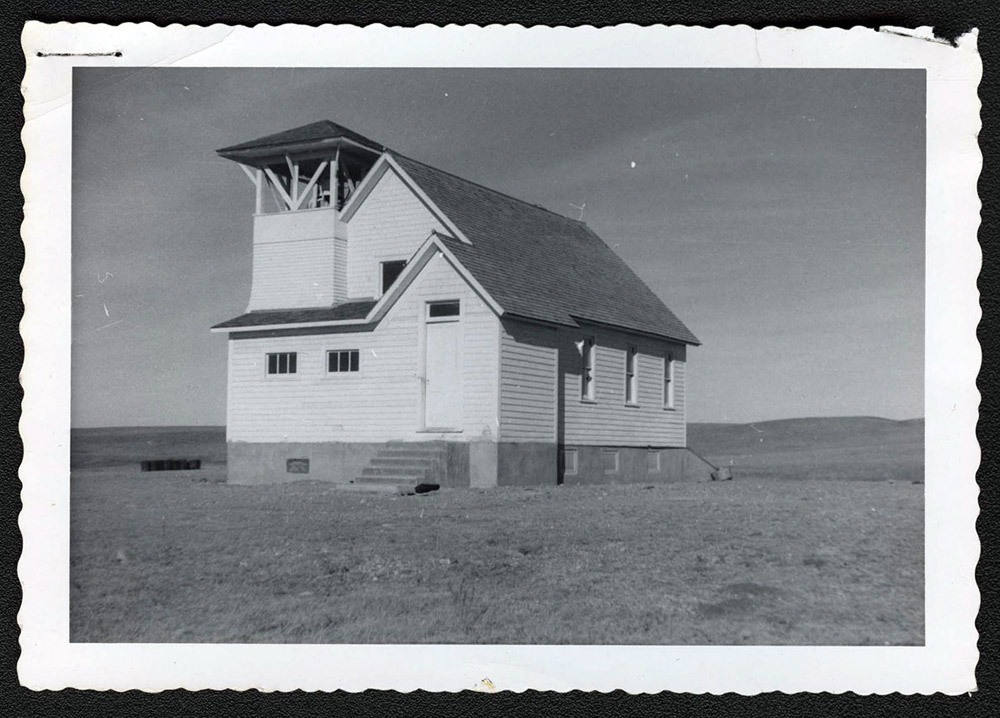

Before the dam was built and the people of the three tribes were relocated, the Fort Berthold Reservation had a governing council, and the people worked their land raising cattle and crops. (See Image 2.) The towns of Elbowoods, Sanish, Independence, and others were comfortable communities where everyone knew everyone else. (See Image 3.) Families raised their children to know and respect the traditions of the past 900 years. Everyone felt connected to family, community, and the land where their ancestors had lived for centuries.

The rising waters forced people to move their homes to high ground, “on top” of the plateaus that surrounded the Missouri bottomlands. Here, on top, winters were harsh and the land was unfamiliar. (See Image 4.) People felt disconnected and unhappy. The hardship destroyed marriages, and children were confused. Poverty took over as unemployment reached 85 percent. People who had previously taken care of their children, in-laws, and neighbors in time of need, were now dependent on federal welfare.

Many people resisted the move. Others simply tried to put it out of their minds as much as possible. More than one family arrived home to see their house being moved to another place. Some followed their houses down the road by car or on horseback to see where the house was going. A few families moved into houses in Parshall or the brand new town called New Town. The new houses had indoor plumbing, electricity and other modern features, but these modern advances did not keep their families together.

When tribal leaders realized the determination of the federal government to go ahead with the dam in violation of treaty rights and federal Indian policy, they realized that they would not only have to adjust, but they would have to incorporate lawyers and accountants into their tribal organizationMany of the members of the Three Affiliated Tribes who relocated to distant states, returned many years later. Some came back with the education and skills to help bring the tribe back to a sound footing. One of these was Alyce Spotted Bear. She returned to the reservation from New York where she was a professor of history. Spotted Bear was elected chair of the Three Affiliated Tribes in 1982. When she took over, the tribe was in debt, poverty was widespread, and people lacked hope that the situation might improve. After consulting with the elders, she made a plan for putting the tribe’s business affairs in order and to alleviate hunger and poverty on the reservation. She was aided in her efforts by Raymond Cross, the son of Martin Cross. Raymond had spent much of his childhood in California and had a law degree from Stanford University. With a clear eye on tribal history and on federal Indian policy and law, the Three Affiliated Tribes looked to a new future. to protect their rights in the future.

The towns and ranches of Fort Berthold disappeared under the water, but the people who once lived there did not forget the importance of those communities. Young Martin Cross, the son of Chairman Cross, remembered growing up at Elbowoods. “There was nothing easy about that life. It was tough, but we laughed and we sang and we never stopped dancing. When people say ‘Elbowoods,’ they’re not remembering the actual place as much as a state of being and spiritual peace. When you mention Elbowoods to the old people, they turn their heads away. They go off by themselves and weep.”

Why is this important? The Three Affiiliated Tribes led the way as Indian nations challenged federal policy. Tribal chair Martin Cross challenged Congress and the Bureau of Indian Affairs many times in the early 1950s. Though the tribes lost many of these legal battles, they developed an understanding of their new position in relation to the federal government. Many of the tribes’ legal concepts that would eventually be incorporated into President Nixon’s new policy called Self-Determination. Nixon declared, as had Martin Cross twenty years earlier, that Indian tribes could be “independent of federal control without being cut off from federal concern and federal support.” This new policy put an end to termination and relocation. Though Self-Determination has some flaws, it reflected what the tribes had proposed as a more workable relationship between the tribes and the federal government.

Resources: Paul VanDevelder, Coyote Warrior (2004); and “Waterbuster,” a 2006 documentary film by J. Carlos Peinado and Daphne Ross.