Though most of Dakota Territory’s earliest pioneers came for land and intended to farm, cities and towns grew up in every county. Most of the towns served farmers’ needs with hardware and lumber stores, grain elevators, and general stores where farm families could purchase such things as clothing or kerosene for cooking, heating, and lighting.

A few cities had other roles to fill. Some towns became county seats where the county government was headquartered. A county seat would have offices for the county court, the sheriff’s office and jail, and a county clerk to collect taxes. Bismarck was not only the county seat and a farm service town, but the state capital with offices of state government. Other towns such as Fargo became financial centers where bankers bought and sold land and securities and traded in grain. Banks also provided loans and other services to shopkeepers and homeowners. Cities were often railroad centers where trains and railcars were repaired, fueled, and stored.

Cities attracted professionals such as doctors, lawyers, and educators. The larger cities had high schools, business colleges, and colleges founded by churches. Fargo also had the state Agricultural College. Grand Forks had the University of North Dakota. Some of the colleges also had preparatory schools for students whose families lived far from a town with a high school. These students lived in a boarding house while they studied in a town far from home.

Why is this important? Most North Dakotans lived and worked on farms until 1990. The cities provided necessary services to farm families and the farm economy. Neither the cities nor the farms could exist independently of the other.

Fargo

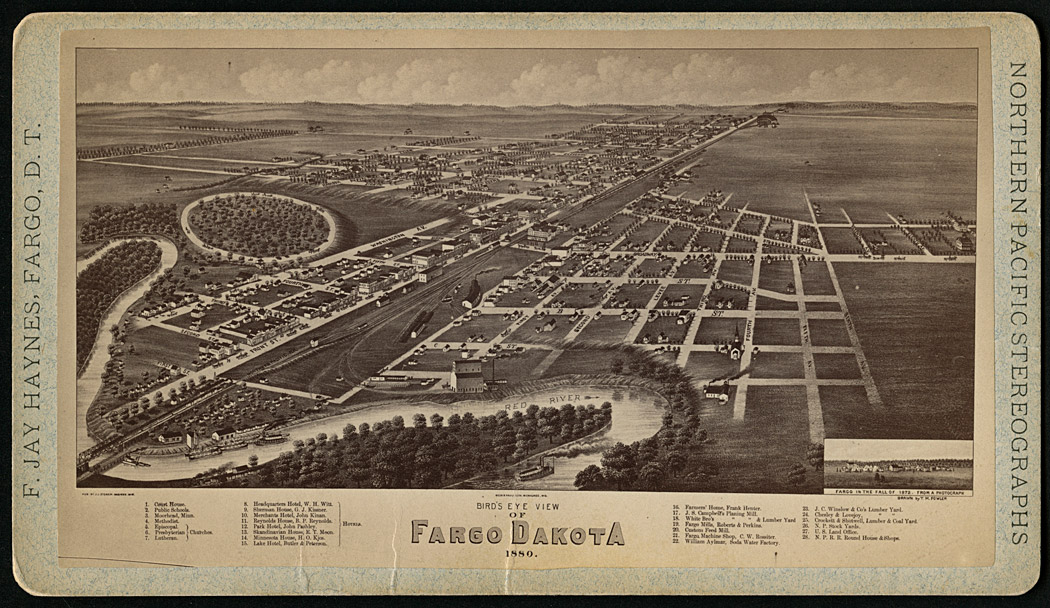

Fargo has been North Dakota’s largest city since the 1880s. It started as a collection of huts along the edge of the Red River known as “Fargo in the Timber.” This little community of 600 rough and rowdy squatters (people who lived on land they did not own) lived by working on steamboats or by some less respectable occupations such as gambling.

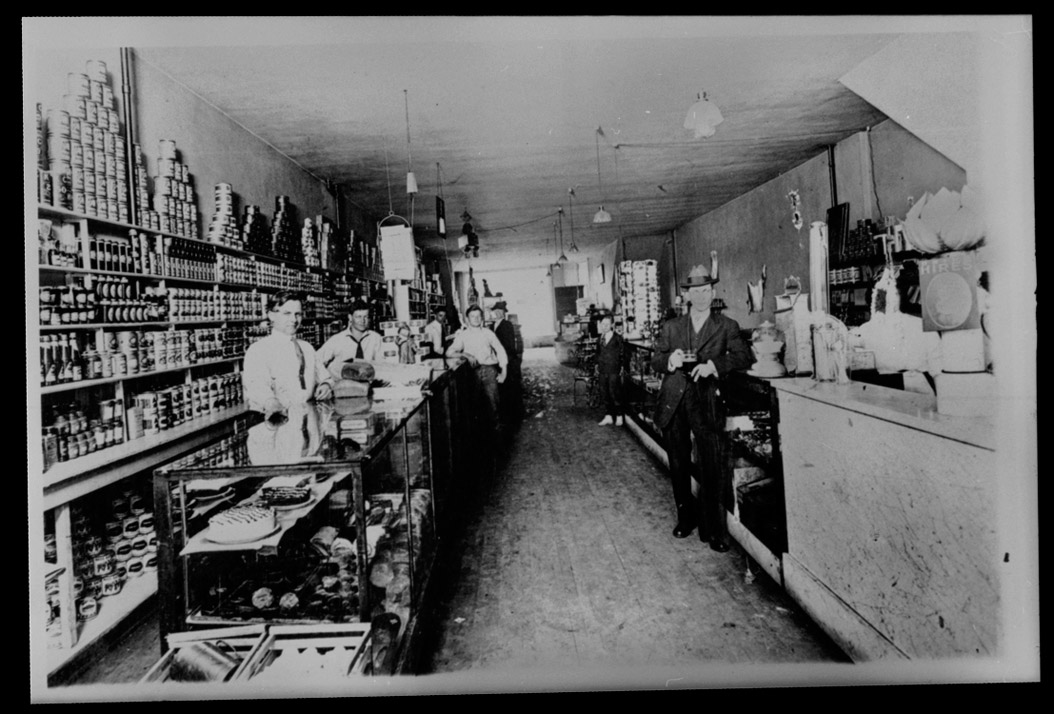

In June, 1872, the Northern Pacific Railroad (NPRR) tracks crossed the Red River into Fargo. A second settlement greeted the NPRR. This community was called “Fargo on the Prairie.” (See Image 1.) Fargo on the Prairie was farther from the river and provided homes and businesses for railroad engineers, merchants, and professionals such as medical doctors. (See Image 2.) The two communities eventually joined to become the young city of Fargo. (See Image 3.)

Fargo’s growth depended on the agricultural economy of the Red River Valley. (See Image 4.) The settlement of small farms and large bonanza farms made Fargo an important shipping and business center. (See Image 5.) Fargo’s rail lines connected the Hard Red Spring Wheat farms of the valley to the flour mills of St. Paul.

The Northern Pacific faced competition from the Great Northern Railway in the 1890s. The presence of two rail lines made Fargo even more important as a business center. (See Image 6.) With grain trade and transportation as its economic foundation, Fargo’s population boomed.

|

Date |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

1910 |

1920 |

|

Population |

2,693 |

5,664 |

9,589 |

14,331 |

21,961 |

This growth occurred while the population of the United States was also growing quickly. However, while the U.S. population nearly doubled between 1870 and1900, the population of Fargo grew 3.5 times larger between 1880 and 1900. Most of the residents of Fargo had been born in the United States. The largest group of foreign born residents had come from the Scandinavian countries of Sweden, Norway, and Denmark.

Fargo’s active economy opened opportunities for women to find employment. (See Image 7.) Most women worked as household servants, nurses, or teachers. Women also worked in retail stores, dairies, and restaurants. Educated women could work as stenographers (workers who typed letters and records for businesses) and in retail. Two hospitals in Fargo had training programs for nurses. Many young women who left their farm homes went to Fargo to find work.

The city offered many educational opportunities. (See Image 8.) Fargo’s first high school opened in 1882, and Fargo College opened in 1887. North Dakota Agricultural College organized as a land-grant college in 1890 before its buildings were ready. Today, NDAC is North Dakota State University. Dakota Business College opened in 1893.

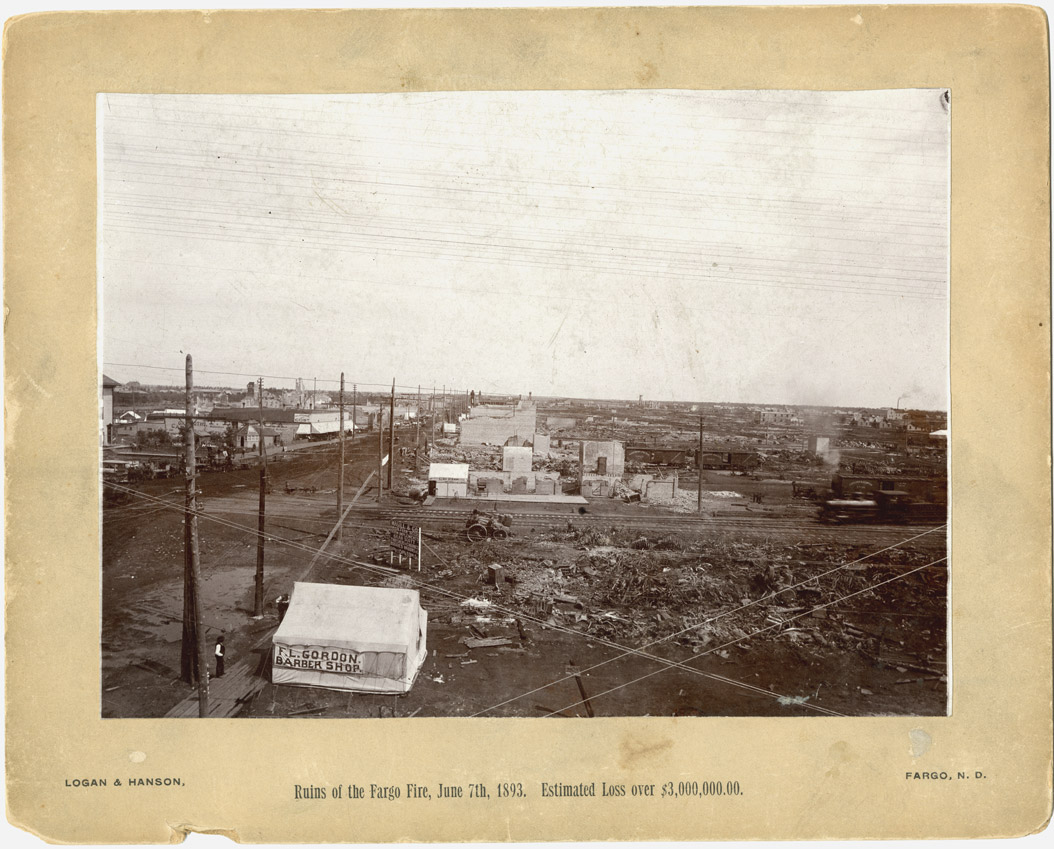

In 1893, about three-fifths of the city’s buildings were lost in a major fire. While the loss was tragic, the fire forced Fargo’s property owners to re-build and expand. The new buildings were mostly of brick. (See Image 9.)

The city had a problem with typhoid fever that was probably caused by contaminated drinking water. (See Image 10.) The city’s water supply came from the Red River, which also served as a sewer for other cities along the river’s banks. In 1912, Fargo built a new water treatment plant that provided safe drinking water to the city’s homes. However, by 1915, only one-third of Fargo’s 2,900 homes had connected to the city’s water system and even fewer homes had connected to the sewer system. These households used simple outhouses instead of indoor bathrooms. (See Image 11.)

Fargo’s middle-class citizens tended to live northwest of the business district. The wealthy lived south of the railroad tracks along 8th Street. The poor lived close to the river, just south of the tracks. A 1915 survey of the city’s poor residents found 111 permanent residents living on one block. That neighborhood increased in population during the winter when farm workers moved to the city to wait for the next summer’s employment.

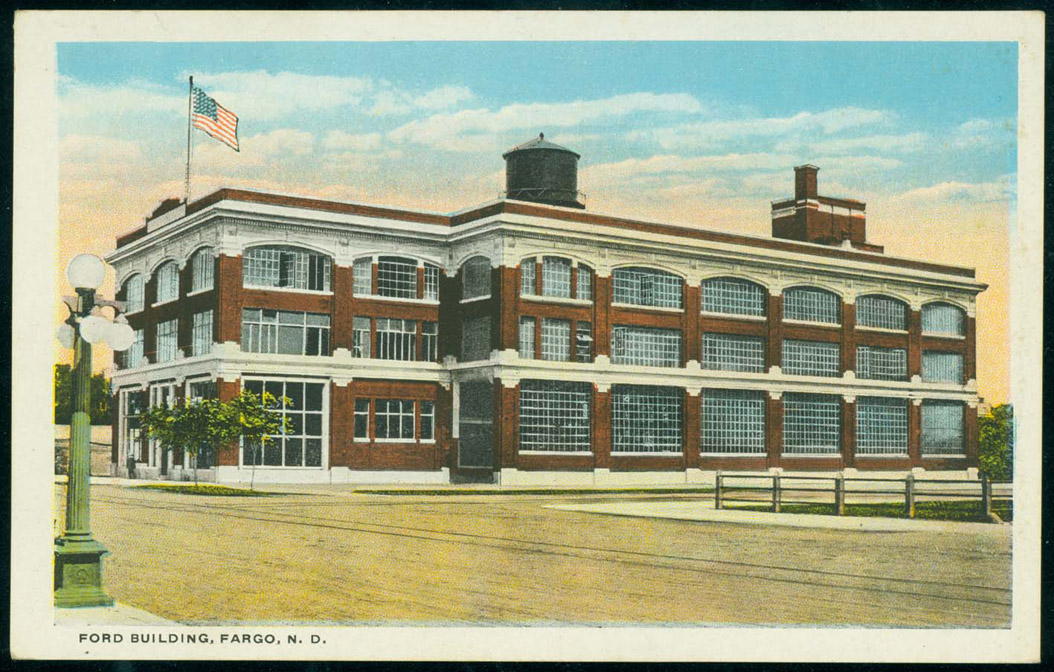

After 1910, Fargo modernized rapidly. (See Image 12.) More than 11 miles of Fargo streets were paved with wood blocks, concrete, brick, or a new “hot mix” asphalt called bithulithic. Street lights were installed on 8th street in 1916. Much of the change in the streets was brought about by the use of automobiles. (See Image 13.)

With its economic growth came political power. Fargo merchants helped to bring the capital to Bismarck in 1883. Fargo was the political center of Cass County, known to the rest of North Dakota as “Imperial Cass.”

Why is this important? North Dakota’s agricultural economy supported the growth of cities. Fargo was the largest and most important North Dakota city, even before statehood. It was the most important retail (shopping) center between Minneapolis, Minnesota and Spokane, Washington for many years. It was the first place that visitors traveling on the Northern Pacific railroad saw as they entered North Dakota. The progressive city surrounded by fertile farm fields made a good impression on newcomers.

Ethnic Diversity

North Dakota’s cities were more racially and ethnically diverse than rural communities. African Americans made land claims and farmed as did Jews in small, scattered communities. However, African Americans, Jews, and a few Asian immigrants found work, homes, and social life in the state’s towns and cities. (See Document 1.)

Throughout North Dakota’s history, more African Americans lived and worked in cities than on farms. The men worked as day laborers, steamboat hands, and railroad workers. (See Image 14.) Many African American men worked as barbers in small towns and cities, a job that gave them the opportunity to own their own business and acquire property. A few African American men were professionally employed as musicians or doctors.

Although most black women did not work outside of their homes, those who did often worked in private households as cooks and servants. Some worked in restaurants as cooks or dishwashers. Others worked in their own homes doing laundry for others. Educated women sometimes were able to find work as school teachers. (See Image 15.) One of these was Mattie Anderson who taught at Venturia School from 1907 to 1914.

W. H.W. Comer arrived in Bismarck in 1873 and set up a barber shop which he advertised as “neat and clean Hairdressing and Bathing Rooms.” (See Image 16.) Comer, who was possibly born free in Massachusetts, had come to Dakota Territory to work as a barber at military posts. Bismarck offered him an opportunity to set up his own business and to purchase property while the city was just beginning to grow. Comer and his wife Virginia became prosperous and respected residents of Bismarck. Comer was included among the first grand jurors appointed in Burleigh County in 1874. His clients were among the leading citizens of Bismarck and he considered some of them as personal friends. (See Image 17.) Comer died in 1888, but his wife continued to own and manage the city property that they had purchased.

Many African Americans enjoyed the respect of their white neighbors and prospered in their work, but North Dakota was not paradise for African Americans. In the cities, vandalism, verbal abuse, and threats were directed toward African Americans or their property. Black men and women who traveled outside of their own neighborhoods to towns where they were not known, often heard racial slurs and hurtful comments. In 1909, the North Dakota legislature passed a law that outlawed interracial marriage or cohabitation. Violators could be punished by imprisonment and fines. The law was not revoked until 1955.

While lynching (a horrible and public form of murder) occurred frequently in southern states during this time period, it was rare in Dakota. However, there were at least two lynchings and some black men were threatened with lynching. In 1882, blacksmith Charles Thurber was taken by force to Grand Forks after being accused of raping two white women. The evidence was not strong, but a mob of 200 lynched Thurber by hanging him from the railroad bridge over the Red River. Thurber had not been tried or convicted of any crime. Years later the two accusers confessed to having lied about the crimes.

The number of African American residents was not large in this time period (it peaked at 617 in 1910) and the hard times of the 1930s forced many to leave for better opportunities. By 1940, only 201 African Americans lived in North Dakota. In recent years, immigration and excellent job opportunities have brought more African Americans to the state.

Jews found Fargo a welcoming city where they were able to engage in commerce and city politics. Many Jews that emigrated from cities of Europe had experienced legal restrictions that prohibited them from owning land and confined them to certain occupations. Jews also saw Fargo as a place where they could prosper as the city grew. By 1913, there were about 100 Jewish families in Fargo. [Document 1]

Jews settled elsewhere in North Dakota, too. There were communities of Russian Jews who settled on Homestead claims near Devils Lake and Painted Woods Creek south of Washburn. Jews lived and worked in smaller towns around the state as well. Though many of the Russian Jews who lived on farms eventually left the state, the Jewish population of Fargo remained fairly stable.

One problem that Jews faced in North Dakota’s cities and farms was forming a congregation big enough to hire a rabbi and build a temple. In 1897, Fargo’s Jewish residents formed a congregation. In 1908, they built a temple. Though the Jewish population remained relatively small as the city of Fargo grew, Jewish residents continued to find Fargo a welcoming city.

Why is this important? North Dakota had an ethnically diverse population from the earliest years of non-Indian settlement. People from different countries, different faiths, and different traditions all found a place to live on the prairie. In part, this diversity was due to the time period when North Dakota settled. These were the decades of great immigration to the United States from all parts of Europe. In addition, North Dakota welcomed all immigrants who could contribute to the state’s economic growth.

Frithjof Holmboe’s Films

Throughout the 19th century, inventors and photographers tried to capture motion on film. In 1891, Thomas A. Edison and his associate, William Dickson, patented a machine called the kinetograph. The images produced were shown through a machine called a kinetoscope (kinesis is the Greek root word for movement.) In 1897, Robert W. Paul invented a rotating camera that allowed filmmakers to shoot panoramas, or scenes that move from one place to another.

By 1905, filmmakers were showing novelty films in theatres around the United States. Although the film subjects were often animals, such as running horses, or events like a man sneezing, film proved to be a popular form of entertainment. These films were usually only a few minutes long and did not have sound.

While the silent movie industry grew, individuals began to purchase film equipment for local or home use. In North Dakota, one of these early filmmakers was Frithjof Holmboe. Holmboe was born in Norway in 1879. His parents moved their family to Minneapolis in 1882. When Holmboe was a young man, he became a photographer for the Northern Pacific Railroad. This job brought him to North Dakota.

In 1907, Holmboe married and moved to New Salem, North Dakota where he set up a photographic studio. In the studio he photographed individuals, but he also took photographs of local events.

Holmboe moved to Bismarck in 1909 and opened a studio on Main Street. He became interested in motion pictures and created the Publicity Film Company in 1913. One of his clients was the North Dakota Department of Immigration. He also worked for businesses that wanted to use motion picture film to promote their products. Holmboe accompanied Governor Hanna to Norway in 1914. There, he filmed the governor’s presentation of a statue of Abraham Lincoln to the city of Oslo.

Frithjof Holmboe’s films are a visual historical document of work and town life in North Dakota. (See Document 2) His films, most of which are dated 1916, show people shopping, working, playing, loafing, driving automobiles, and riding horses. Pedestrians, especially children, watch carefully for automobiles before crossing the streets. Both horses and automobiles were used for transportation. Holmboe also shot film of trains and airplanes. Frithjof Holmboe left North Dakota for California when the economic depression that followed World War I took much of his business.

Document 2. Holmboe's Films

These films were made in 1915 and 1916 by Frithjof Holmboe of Bismarck. They document urban life in the early 20th century. Each film is quite short. There is no sound.

Wilton and vicinity. 2 min, 54 secs.

Killdeer and vicinity. 4 min, 5 secs.

Children and Families in Mandan Park. 28 secs.

Bismarck. 55 secs.

Bi-plane. 5 secs.

Ferry Boats on the Missouri River. 12 secs.

Why is this important? Frithjof Holmboe was a pioneer of technology. He used technology to record events during a time when technology was changing the way North Dakotans worked, traveled, and conducted business. Holmboe’s films are primary documents that show how ordinary people lived and worked in North Dakota's cities and towns.