Farm workers, both men and women, were scarce on North Dakota farms. There was work for men in the fields, but there was more demand for workers in the house. Young girls often filled this role of domestic worker. In North Dakota, young women who went to work in someone else’s home were usually called the “hired girl,” or just, “the girl.”

The hired girl’s work lasted from very early in the morning until late in the evening. Her tasks usually included cooking, washing dishes, and caring for young children. Once a week, the girl washed clothes and ironed them. Many hired girls were also required to mend clothing. On many farms, the girl worked alongside the housewife. However, a girl who worked in an upper class city home worked alone and had to learn to do the work according to her employer’s standards.

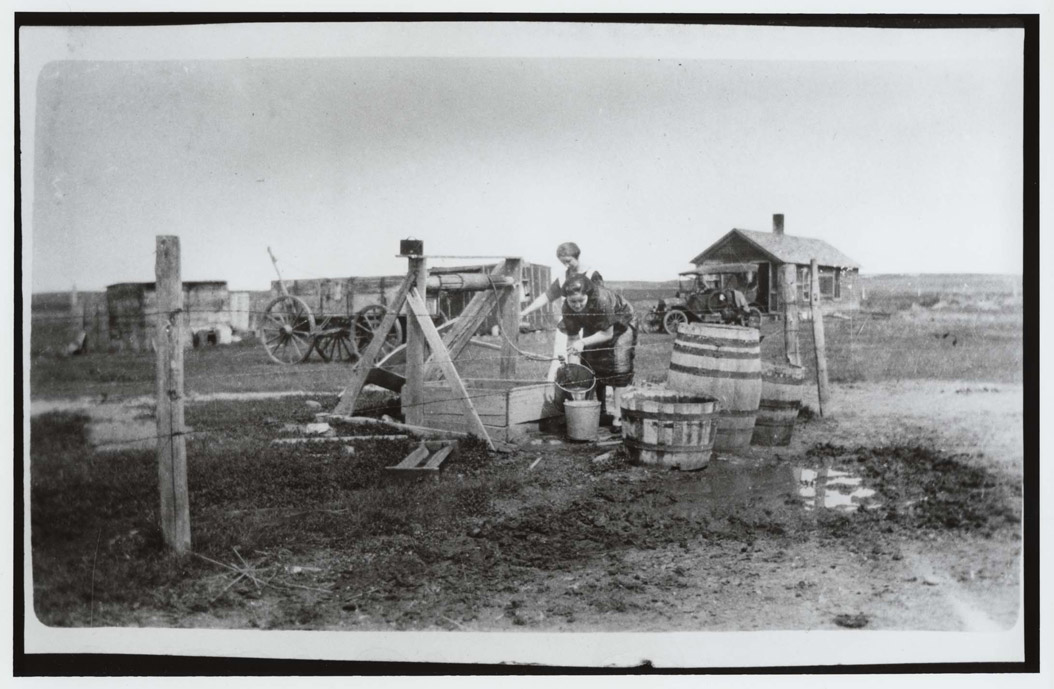

Household work was very difficult in the years before electricity and running water was available in homes and on farms. The girl had to carry buckets of water from a well. (See Image 1) She had to chop wood for heating water and cooking. The girl made bread and other foods from "scratch." The hired girl washed clothes in a tub using a scrub board and harsh soap. (See Image 2) Washing usually took place outdoors. (See Image 3) In addition, she gathered eggs and milked the cow.

The work was very hard, but it had some advantages for a young girl. The work helped her to learn to manage a household. These skills would help her run her own home when she married. She earned cash that she could keep for her own use or education, but some girls sent the money home to help their families. Sometimes, a hired girl worked only for room and board (no wages). In exchange for her labor, she had time to attend high school in a city.

Immigrant girls found work that allowed them to live independently of their families. However, immigrant girls were often in conflict with their American employers. They had learned a different way to keep house in their immigrant mother’s homes, but they had to learn how to keep house as Americans did in order to please the employer. Many women believed that immigrants did not keep a clean and orderly home. This prejudice sometimes made a hired girl’s working experience very difficult. An employer who was very unhappy with a girl’s ability or cleanliness might dismiss the girl from the job. The scarcity of hired girls, however, meant that a girl could find a new job quickly.

There were some dangers to hired girls. They were away from the protection and guidance of their parents. Sometimes, if they were working in a city, they might take up bad habits such as drinking on their day off. Some girls, having money to spend for the first time, spent their money unwisely. Some employers were unkind. If an employer refused to pay a girl for her work, it was hard for the girl to collect back wages.

Thousands of North Dakota farm girls took jobs as domestics. How they felt about this work varied with the situation. Kjersti Raaen enjoyed her work because she earned good wages and her employer was kind to her. Other girls, however, found their work overwhelming, especially if they worked for a large family. Girls who had just arrived from another country often did not understand that they could demand to be paid reasonable wages, take one day off each week, and find another job if the one they had did not work out well.

Hired girls might leave home for work when they were as young as 12 years old, but most did not hire out until they were about 16. Many hired girls married before they were 25, so they worked as a domestic for only a few years. Some women returned to domestic work if they were widowed late in life.

Why is this important? In the United States in 1900, more women were employed in domestic work than in any other type of job. Housework was considered too difficult for one woman to do alone. Therefore, many households hired someone to help. The work was beneficial to girls because the wages were good and there were plenty of jobs to choose from. Historians have found that almost all farm girls in North Dakota worked in someone else’s home for at least a few years before they married. It was the most common experience for young girls between 1870 and 1915.

Document 1. Two Hired Girls’ Experiences

Most young women went through a spell of “hiring out” in their teens. Employers expected that by the age of 13 or 14 girls could do most household chores except for skilled work like fine sewing. “Working out” was thought to be good training for later life when a woman had to manage her own household. Caroline Gjelsness became a wife and mother. Aagot Raaen became an educator who was superintendent of Steele County schools. Kjersti Raaen died at the age of 20.

Kjersti and Aagot were sisters who lived on a farm in Steele County. Their parents immigrated from Norway and the girls grew up speaking the Norwegian language at home, but did not speak English. Working as a hired girl meant that they had to learn English and American ways. Both girls thought that work would help them achieve their dreams. Aagot and Kjersti had an older sister, Julia, who began working out at the age of 12. Source: Aagot Raaen, Grass of the Earth. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1994.

“Aagot says most of the women in Hope don’t work, the hired girls do that. The women do things they like and they visit one another a lot. If I could do as I like I wouldn’t go visiting. I would go to a big city and learn to make beautiful clothes, fine lace, and embroidery. I would learn how to prepare the best food and how to take care of children and sick people.” Page 127- 128.

Aagot tried to learn dressmaking, but found a job as a domestic. Kjersti commented: “Everyone wanted her for a hired girl, but not everyone wants her for a dressmaker.” Page 129.

“I [Kjersti] am working for the Hoyts in Northwood, about six miles from home. They are Yankees. It is a big house full of beautiful things. When I told [mother] about the rugs and carpets on the floor she wouldn’t believe me. The food is all different, too. I didn’t think I could learn so many new things, but Mrs. Hoyt worked right with me the first three weeks. Yesterday I made a cake, it did not turn out right. When Mrs. Hoyt saw I felt unhappy about it, she said, ‘You are clean, orderly, and careful, and that is worth much more than being able to make cake.’” Page 131

She is very kind; when I have headaches, she helps me with the work. I get $2 a week; as soon as I can do everything alone she will pay me two dollars and a half, and if I become very good I’ll get three dollars, later maybe more. I have been here a month and have eight big round silver dollars. I wonder if I have done enough work for all the money.” Page 131.

Caroline Olsen corresponded with Marius Gjelsness before their marriage in 1888. Both had immigrated from Norway. Caroline had come to the U.S. on her own without her family. While Caroline and Marius were courting, Caroline worked in several different homes near Grand Forks. In 1892, four years after they married, she returned to Norway for a visit. Her letters to Marius concern the hired girl who worked for him and the girl she wanted to hire in Norway to bring to the U.S. to work for them. Source: Gelsness Papers: Orin G. Libby Manuscript Collection 1233, Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Collections, Chester Fritz Library, University of North Dakota. Translated by Orville Bakken, Compiled by June Tweten.

Caroline to Marius, February 19, 1887. “When I have done my work, then I am through, whether it is early or late.”

Caroline to Marius, March 23, 1887. “Yes, you do not get any interesting letters now when I have to take care of little Hazel this evening. She calls and shouts and talks so I cannot concentrate at all. I do not know at all what time I shall have the opportunity to write a good letter to you for I always have this girl to bother me.”

Marius to Caroline, April 22, 1887. “It cannot be profitable to stay where you can never get any rest. That is something that nobody would continue doing. It is just to lose your health even though you are strong as a horse. You did not come to America to work like a slave, because America is not so mean to be in.”

Caroline to Marius, December 13, 1887. “Yes, I have time for [writing letters.] I have gotten a place, a pretty good place I think it is. The wife here is exceptionally nice. Yes I must say it is almost too much. She will not let me sit in my room alone. . . . Everything is easy here. Soft water in the kitchen sink and wood in another room next to the kitchen.”

Marius to Caroline, June 30, 1892. “There is a girl who is a sister of Thori Larson who came from Norway this spring. She has hired herself to Anton Lybakken for $2.50 a week til harvest starts and later shall have $3 and I think that is a lot for a newcomer but girls are about impossible to find for these wages here in North Dakota. The best thing you can do is to find a girl before you come back and then you can also have help on the trip. Do not take anyone along unless you understand that it is her complete desire to go to America and someone that does not have it good in Norway if someone like that can be found.”

Caroline to Marius, August 7, 1892. [I have offered to hire a girl in Norway at a wage that is] “necessary and possible for a newcomer . . . and that is usually $1.50 per week.”