On March 2, 1861, in one of his final acts as President, James Buchanan signed the Organic ActAn organic act allows a government to organize. Congress passed the Organic Act in 1861 that permitted the people of Dakota Territory to organize a government. However, the leading officers of a territory – the governor, the justices of the courts, and the federal marshals – were appointed by the President. The people elected representatives to the legislature.creating Dakota Territory. The news came from Washington by way of train and stage coach. It took 11 days for news to travel from Washington, D.C. to Yankton.

There were a few hundred non-Indian residents in the new territory. Some European American residents lived near Pembina in the northeastern corner of the territory. Others lived in the southeastern corner at Yankton, Vermillion, or Sioux Falls (today, these cities are in South Dakota). The residents were excited and celebrated noisily. One reporter remarked that the celebration “started a jack rabbit stampede for the distant bluffs.”

Territories were governed by men appointed by the President. The President turned to friends in Congress for recommendations. President Lincoln appointed Dakota Territory’s first governor, William Jayne. Governor Jayne was Lincoln’s old friend and neighbor from Springfield, Illinois. The governor’s first and most important duty was to make the Territory conform to federal laws.

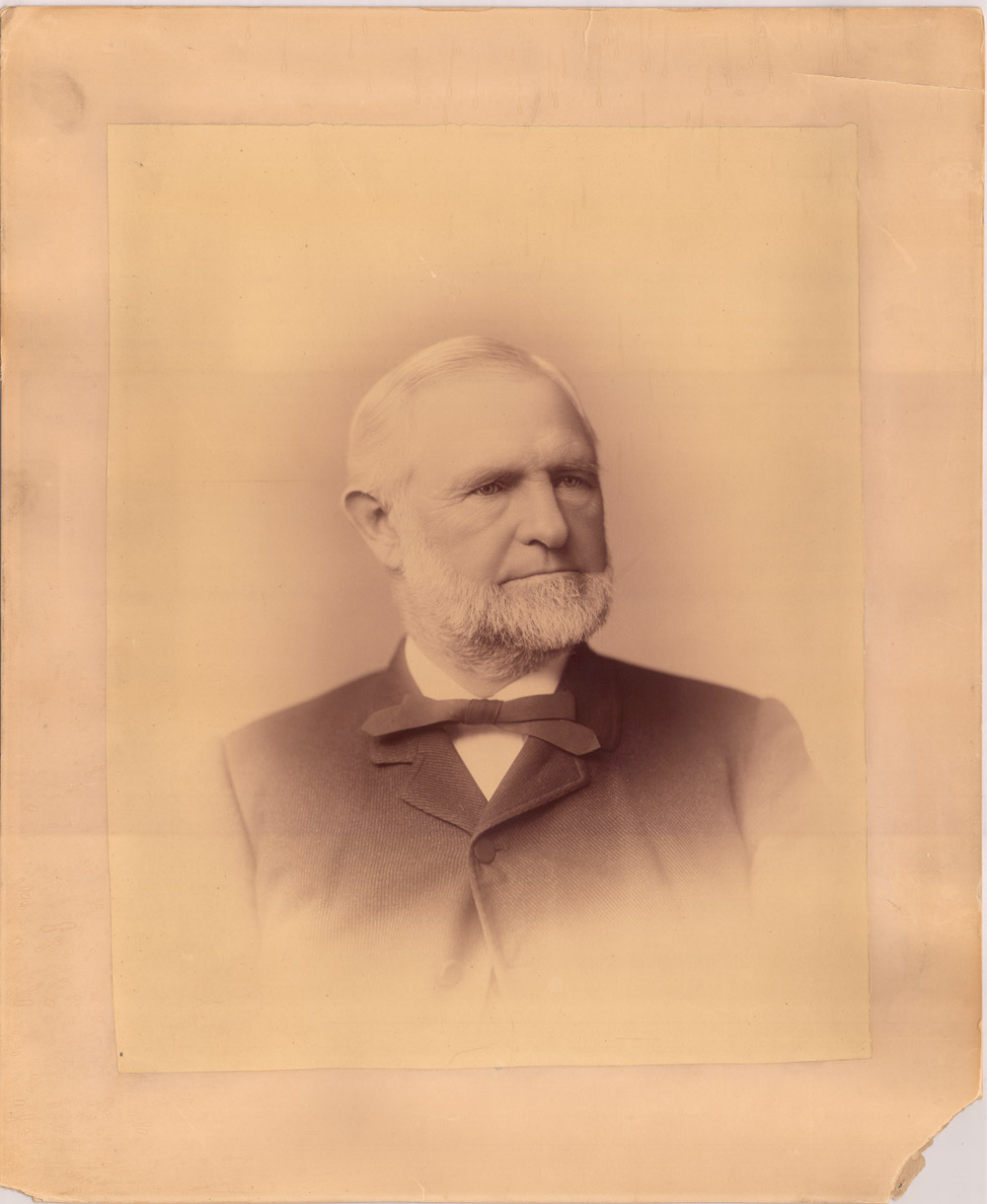

Governor Jayne arrived in Yankton on May 17, 1861. (See Image 1) He moved into a log cabin which he shared with Attorney General W. E. Gleason who also was appointed by Lincoln. Neither man had brought his family along, so Jayne made Gleason act as the housekeeper. The Attorney General had to carry water two blocks from the river to the cabin for their daily needs. Mr. Gleason did not enjoy that part of his job, but he had to acknowledge the importance of the governor by obeying this order.

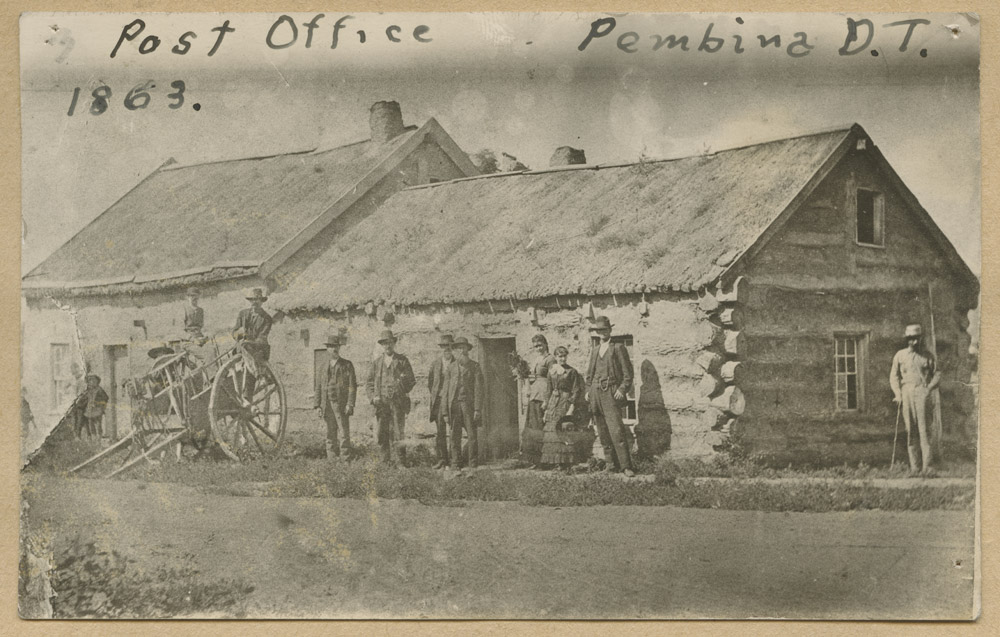

The Organic Act explained what had to be done in order for the Territory of Dakota to follow the federal law. A legislature had to be elected. The members of the legislature had to meet and pass a body of laws. Governor Jayne studied the population of the territory. He found that according to the census of 1860 there were 2,375 non-Indian residents in Dakota. More than half of them lived in the Pembina district, 470 miles north of Yankton. The rest lived near Yankton. There were no roads, no trains, no stagecoaches to carry the legislators (and mail) between these villages.

Governor Jayne decided that all men over the age of 21 could vote in the election. Of course, that did not include “Indians not taxed” as the U. S. Constitution states (Article 1, Sec 2, Paragraph 3). At that time, the few women living in the territory could not legally vote.

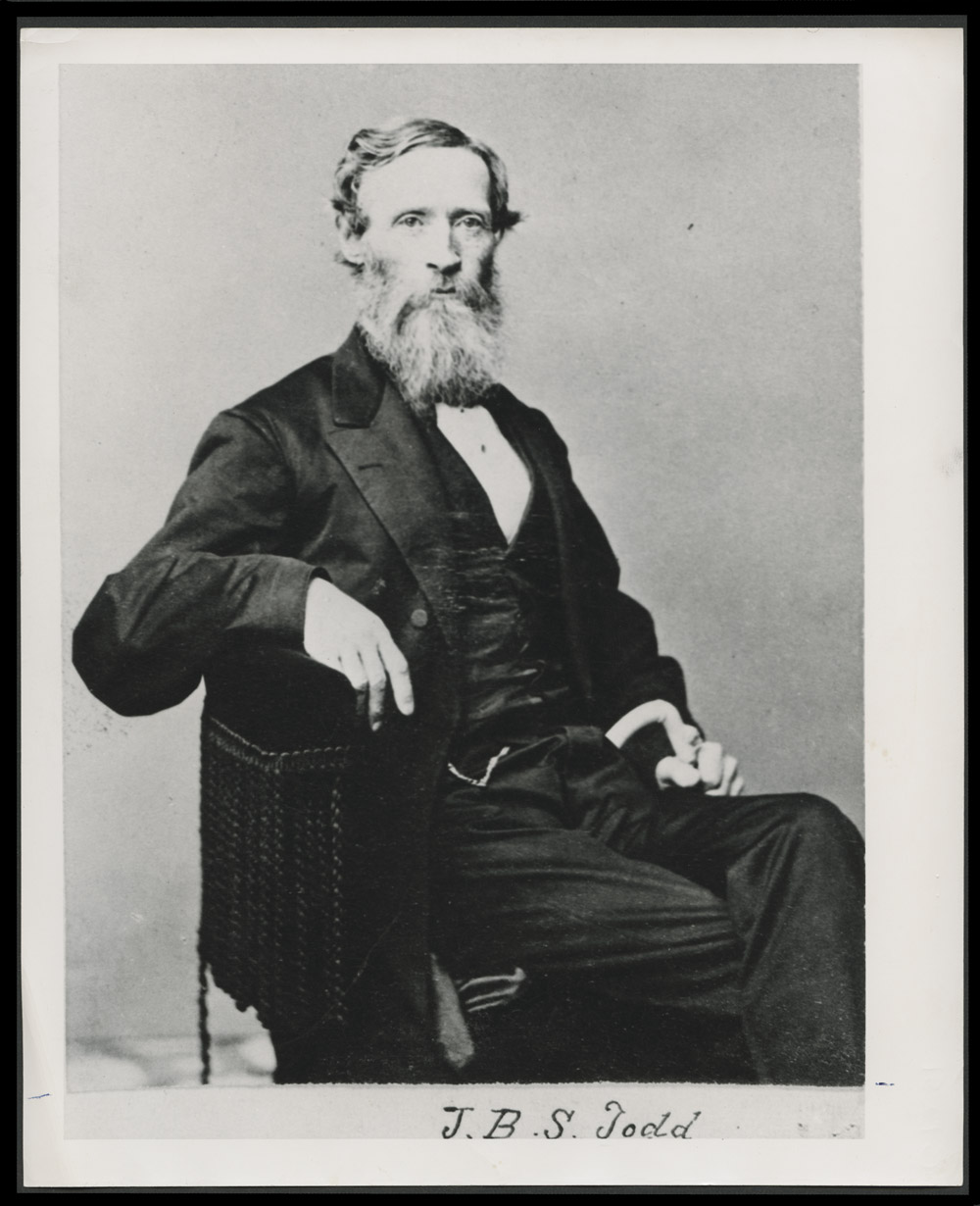

The first election in Dakota Territory was held on September 16, 1861. Citizens elected nine members to the Council (the upper chamber – today it is called the Senate), and thirteen members to the House of Representatives. Voters also elected J. B. S. Todd, (See Image 2) Mary Todd Lincoln’s cousin, to serve as Delegate to Congress from the territory.

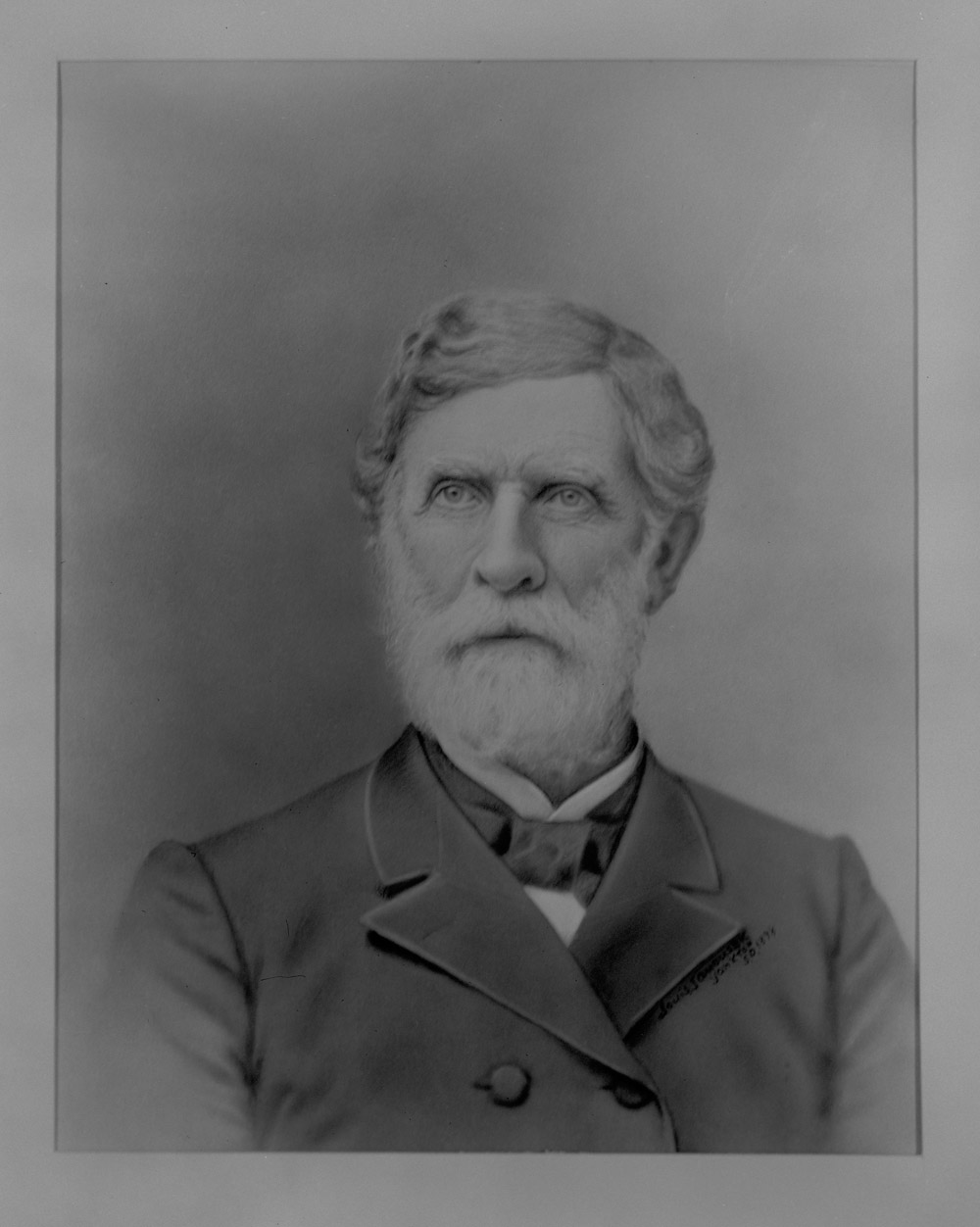

The legislature had a lot of work to do when it met on March 17, 1862. (See Document 1) Legislators passed a body of laws, called common laws, much like those in other states.(See Document 2) These included laws about crime, schools, taxes, elections, and marriage and divorce. Legislators voted to make Yankton the territorial capital. They established 18 counties and drew the boundaries of each.(See Image 3)

Many of these laws were not effective and most were not enforced. The federal marshal did not become a resident of Dakota Territory for several years. There were no jails to house criminals. There was no tax collector, so there were no public schools for the 600 school-age children. (See Image 4)

In 1862, the citizens voted again on a delegate to Congress. A territorial delegate did not have a vote in the House of Representatives, but he could vote as a member of a committee. In addition, he could try to influence Congress to pass laws that favored the territory’s interests.

Governor Jayne was elected to be the new Delegate to Congress, or so he thought. He resigned the governorship. However, his opponent, J. B. S. Todd, challenged the votes counted in the election. Todd argued that fraudulent votes had been counted. Todd won his case and was seated in Congress. Mr. Jayne returned to Illinois. Lincoln appointed Newton Edmunds to serve as the next governor of the territory.

Why is this important? Government provides many services for residents of a territory. Dakota Territory’s government recorded land titles, so no one could take property from the rightful owner. The territorial government established a militia (citizen army) for protection and enforced (eventually) criminal laws. Government also built roads and schools. In a new territory such as Dakota, government provided a few jobs and created a stable society. The legislature passed laws to encourage the building of railroads, grain mills, and livestock markets. The legislature also passed laws to organize elections and create an orderly democracy. Government contributed to building a place where people wanted to live, work, and raise their children.

Making the Territory Work

By 1862, Dakota Territory had a legislature, counties, and a body of laws. (See Document 2.) There were still problems to solve. The election in the fall of 1862 revealed many problems. The legislature had to decide the outcome of elections for Council seats in five of the thirteen electoral districts. Several of the candidates declared that they had lost the election because more votes were cast than there were residents in the district.

Document 2. First Laws of the Territory

Slavery is Kidnapping: The criminal code included a law prohibiting kidnapping. In Dakota Territory, slavery was outlawed as a form of kidnapping. In 1862, slavery was still legal in several states.

“Every person who shall hire, persuade, entice, decoy, or seduce, by false promises, misrepresentations, and the like, any negro, mulatto, or colored person, not being a slave, to go out of this territory, or to be taken or removed therefrom, for the purpose and with the intent to sell such negro, mulatto, or colored person into slavery or involuntary servitude, or otherwise to employ him or her for his or her own use, or the use of another, without the free will and consent of such negro, mulatto, or colored person, any person so offending shall be deemed to have committed the crime of kidnapping, and upon conviction thereof, shall be punished as in the preceding section.” Laws, 1862: Criminal Procedure. Chapter 9. Section 54.

Testifying as a Witness: The laws outlined the duties of citizens. It is the duty of every citizen to serve on a jury or take an oath as a witness when necessary. When the criminal code of law defined a witness, it also defined citizenship in the territory. The law stated: “All persons capable of understanding the nature of an oath (except negroes and Indians) shall be competent witnesses unless otherwise declared by law.” Laws, 1862: Criminal Procedure. Chapter 9. Section 16.

Jury Duty: Citizens had the duty of serving on juries. The law stated: “All free white males residing in any of the counties of this territory, having the qualifications of electors, and being over the age of twenty-one years, and of sound mind and discretion, and not being judges of the supreme court . . . are, and shall be competent persons to serve on all grand and petit juries within their counties respectively. . . .” Laws, 1862, Juries. Chapter 52. Section 1

Who Can Vote: One duty of citizenship is voting. Voters had the right to vote in elections even if they lived in a part of the territory that had not been established as a county. Voters were defined by law:

“Every free white male person above the age of twenty-one years, who shall have been a resident of the territory ninety days prior to any election, and who is a citizen of the United States, or has declared on oath his intention to become such, and shall have taken an oath to support the constitution of the United States, shall be entitled to vote; and all persons possessing the qualification mentioned in this section, and who have resided in this territory nine months, shall be eligible to any office within said territory.” Laws, 1862, Elections. Chapter 32. Section 51.

Marriage: The Legislature had the right and obligation to pass laws concerning the age of marriage and the legal limitations on marriage partners as well as how to obtain a marriage license. Marriages could be performed by a minister, a justice of the peace, or a judge.

“A Marriage between a male person of sixteen, and a female of fourteen years of age is valid; Provided, That nothing in this act contained shall be so construed as to permit of the intermarriage of white person with person of color; nor of the intermarriage of persons who are related to each other by blood nearer than second cousins.” Laws, 1862: Marriages. Chapter 59. Section 2.

Divorce: The terms of divorce were not covered by law. Any couple who decided to divorce had to ask the legislature for a special “bill of divorce.” The first legislature passed two bills of divorce. One divorce was granted to Minnie Omeg, a recent immigrant from Germany. The legislature allowed her to keep all her property and custody of her children. Laws, 1862. Private Laws. Chapters 4 & 5.

Schools: The School Law details the duties of the Superintendent, the school boards, and other school officers. The law provided for the collecting of taxes to support the schools. Teachers were required to file a report on attendance and a summary of the course of study at the end of each term.

“The district Schools established under the provisions of this act, shall at all times be equally free and accessible to all the white children resident therein over five and under the age of twenty-one years, subject to such regulations as the district board in each may prescribe.” Laws, 1862: Schools. Chapter 81. Sect 40

“In every school district there shall be taught orthography [the rules of writing and grammar], reading, writing, English grammar, geography, and arithmetic, if desired, during the time the school shall be kept, and such other branches of education as may be determined by the district board.” Laws, 1862: Schools. Chapter 81. Section 41.

Taxes: Dakota Territory tried to encourage agriculture and business by providing tax advantages through the law.

“That the following property shall be exempt [free] from taxation, for the time specified in this act, to wit: 1. All sheep and the wool shorn from the same, while in possession of the producer, for the term of five years. 2. All woolen manufactories, including the machinery of the same, for a term of fifteen years. 3. All cotton manufactories, including the machinery of the same, for a term of twenty years. 4. One half the value of all other manufacturing establishments for the term of five years.” Laws, 1862: Exemptions, Etc. Chapter 40 Section 1.

Towns, Counties, Roads and Rivers: The legislature established Yankton as the capital, or “Seat of Government.” Legislators passed laws to incorporate several towns. They also established the boundaries and county seats of 18 counties. Pembina and its neighboring town, St. Joseph, were in Kittson County (today Pembina is in Pembina County). Roads were to be 80 feet wide; drivers were to move to the right if they should encounter another vehicle. Employers of men who drove stage coaches and freight wagons had to be sure the drivers were not drunk. Legislators passed several laws that required new roads to be surveyed between towns. The legislature asked Congress to build a military road along the west bank of the Red River to Pembina. The legislature granted charters to operators of ferry boats on the rivers and set the price of transportation. (See Image 7) For example, anyone crossing the Missouri River on George Granger’s ferry had to pay $1.00 for a team of horses and a wagon, and ten cents for 100 pounds of goods.

Indians: Though Indians and tribal lands were under federal jurisdiction, the legislature tried to confine Indians and restrict their movements by law.

“No Indian shall be permitted to trespass or enter upon any ceded lands [land Indians had given to the federal government] within this territory, for the purpose of hunting or fishing, or travelling to and from the lands or hunting grounds of different tribes of Indians, without first having obtained a written pass or permit for such purpose from the local United States agent of the tribe to which such Indian or Indians belong, or from the superintendent of Indian affairs in this territory.” Laws, 1862: Indians Chapter 46. Section 1

“Any Indian or Indians found upon any of the ceded lands of this territory, without a pass or permit the duration of which shall have expired, shall be deemed amenable to the laws of the territory, and may be arrested by any citizens of this territory, and placed in charge of the sheriff of the county where such arrest was made.” Laws, 1862: Indians Chapter 46. Section 3.

Brulé Sioux: In a memorial, or letter, to Congress, the legislature asked the federal government to make treaties with the Brulé Sioux and the Chippewa. They asked to have the Brulé Sioux (a band of Teton Dakota) removed from their treaty lands in the southern part of the Territory:

“To the Honorable Secretary of the Interior: Your memorialists, the legislative assembly of the Territory of Dakota, would respectfully represent that the interest of this territory would be greatly promoted, and its early settlement rapidly hastened, if the Indian title to the country now claimed and occupied by the Brulé Sioux Indians was extinguished.

“Only a small fragment of the vast region embraced within the boundaries of Dakota, is open for settlement. These Indians possess a belt of land extending from the Missouri to the Niobrara rivers, and lying next beyond the country ceded in 1858 by the Ponca Indians, including a portion of the valleys of the Niobrara and Missouri Rivers, and all the valley of the White river, together with the country in the neighborhood of and embracing the Black Hills. This region is believed to abound in mineral wealth, and portions of it are well timbered with pine and other valuable forest trees, rendering it – in consequence of the scarcity of timber and fuel in the territory already ceded – of almost vital importance to the future of Dakota. At present, these Indians are a formidable barrier to any further advance into this interesting part of the public domain.

“The cession of their lands to the United States would at once open the door to the gold fields of the north-west, and the pine regions of the tributaries of the Upper Missouri. It will also open the shortest and most practicable thoroughfare leading from all the North-Western states to the western slope of the Rocky mountains.” Laws, 1862: Indian Treaties. Chapter 99.

The legislature also wanted to remove the Chippewa from the region of the Red River in the northern portion of the Territory.

Chippewa: “. . . it has been the policy of the general government to encourage the march of empire in its westward course, and . . . that, by the formation of such a treaty, a beautiful tract of country, which cannot be surpassed for a fertile and exuberant soil, will be opened for settlement, and speedily developed. Your memorialists . . . believe it a matter of vast importance to the commercial interests of the West, that protection be afforded to those engaged in transporting goods from the city of St. Paul and other cities on the Mississippi river, to the British settlements on Red river, and also that protection ought to be afforded to our own citizens engaged in conveying goods to the northern part of the territory.

“And your memorialists would further represent, that the [Chippewas] have endeavored during the past summer to prevent the navigation of the Red river, by taking possession of the steamboat Anson Northrup, when moored at the town of Pembina, for the purpose of changing the United States mail, and that said tribe of Indians have, by numerous threats made during the past winter, exhibited such a spirit of hostility against the use of their country for a thoroughfare for transportation, that little hope can be reasonably entertained for the continuance of said route, unless the Indian title to the country be extinguished and the Indians removed therefrom. Laws, 1862: Indian Treaties. Chapter 100.

Laws of Citizenship: Under the heading “Private Laws,” the legislature passed laws granting citizenship in Dakota Territory to 12 men who were the sons of European American or French Canadian fur traders and Native American women. They were known at that time as “halfbreeds” (a term no longer acceptable today). Though they were born in the United States, their Native American and/or Canadian parentage raised questions about their citizenship. These 12 men had been long-time residents of Dakota and had made important contributions to its economy and status as a territory. Among them were Frank LaFromboise, an interpreter for General Sully, Frank Chardon, and Charles Picotte, both traders.

Fraud was also a factor in the election for Delegate to Congress. J. B. S. Todd, who ran for the seat against Governor William Jayne, claimed that many votes had been counted improperly. He took his case to Congress where Senators frowned on the quarrels in the Territory. Nevertheless, Congress declared Todd the winner in 1864.

Once Governor Jayne resigned, President Lincoln had to decide whom to appoint to be the territorial governor. William Jayne suggested Newton Edmunds. (See Image 5) Edmunds, a Republican, had been a surveyor in Dakota for several years. He knew the people and the place very well. He accepted the appointment on October 17, 1863. His first act was to issue the Thanksgiving Proclamation on October 26, 1863. It was the nation’s, and Dakota’s, first national Thanksgiving Day.

Governor Edmunds knew that there were still serious issues for the territory to solve. Roads had to be built to connect the towns and the military posts. The territorial legislature passed a law that allowed for surveyors to lay out roads. The legislature asked the federal government, through a memorial, or letter, to build “military” roads which civilian mail carriers could use as well. (See Image 6)

Crime was a problem for the territory, too. There were not many criminals in the 1860s, but when there was a murder or a robbery, the suspect had to be arrested and tried. Few counties had elected a sheriff. There were no jails for several years. Convicted criminals had to be sent to the Iowa penitentiary.

When there was a murder on Indian land, the federal marshal should have made an arrest, but as Edmunds pointed out

there is neither (to my knowledge ) a U.S. Marshal or his Deputy, U.S. District Attorney, or a U.S. District Judge within our territorial limits and, . . . however humiliating the admission, I know of no civil authority to whom the prisoner, under the circumstances, could properly be turned over.

The absence of important federal officials continued into 1865. In February, Governor Edmunds wrote to William Burleigh who was then the Delegate to Congress:

The continued absence of U.S. District Attorney who has not been in the Territory for more than eighteen months and our U.S. District Judges who, with the exception of Judge Bartlett, have been gone for months render entirely negative every effort to enforce the laws or bring criminals to justice.

Edmunds worried about how to make a good life for the residents of the territory. In December 1863, when he first addressed the legislature, he said that the laws of the territory should support public schools. He also suggested that laws could encourage immigrants from eastern states or Europe to come to Dakota. The election laws had to be more carefully written and enforced. Finally, he asked the legislature to consider the need for local defense. The U. S.-Dakota War of 1862 came close to the territory’s boundaries. The Dakotas in the northern part of the territory had made it clear that they would defend their treaty lands against railroads and white settlers. Dakota Territory needed a militia.

Edmunds stated in his address to the legislature in 1864, that for the territory to “ be perfect and put in running order our internal machinery, . . . we have to submit to be lightly taxed.” Taxes were first collected in Yankton County in 1864 and a few other counties in 1865. With so few people in Dakota, the tax collections amounted to only $500. Taxes were necessary to pay the expenses of government.

Edmunds continued to serve as governor until August 1866. After he left office, he continued to work toward peace with the Dakotas of Dakota Territory. He stayed in Yankton where he started a bank, a church, and contributed to the first school.

Why is this important? Governor Jayne established the legislature and other requirements of the federal law. The second governor, Newton Edmunds, had the difficult job of making this huge and sparsely populated territory work. He asked federal officials to do their jobs. He made it possible for the children of the territory to attend public schools. He asked the legislature to face up to the unwelcome, but necessary, task of taxation. Together, Governor Jayne and Governor Edmunds took a small group of scattered settlers in a huge land, and created an organized territory that prepared to become a state. The next governors made more changes, but the framework was created for them by Governors Jayne and Edmunds.

Letters to the Governor

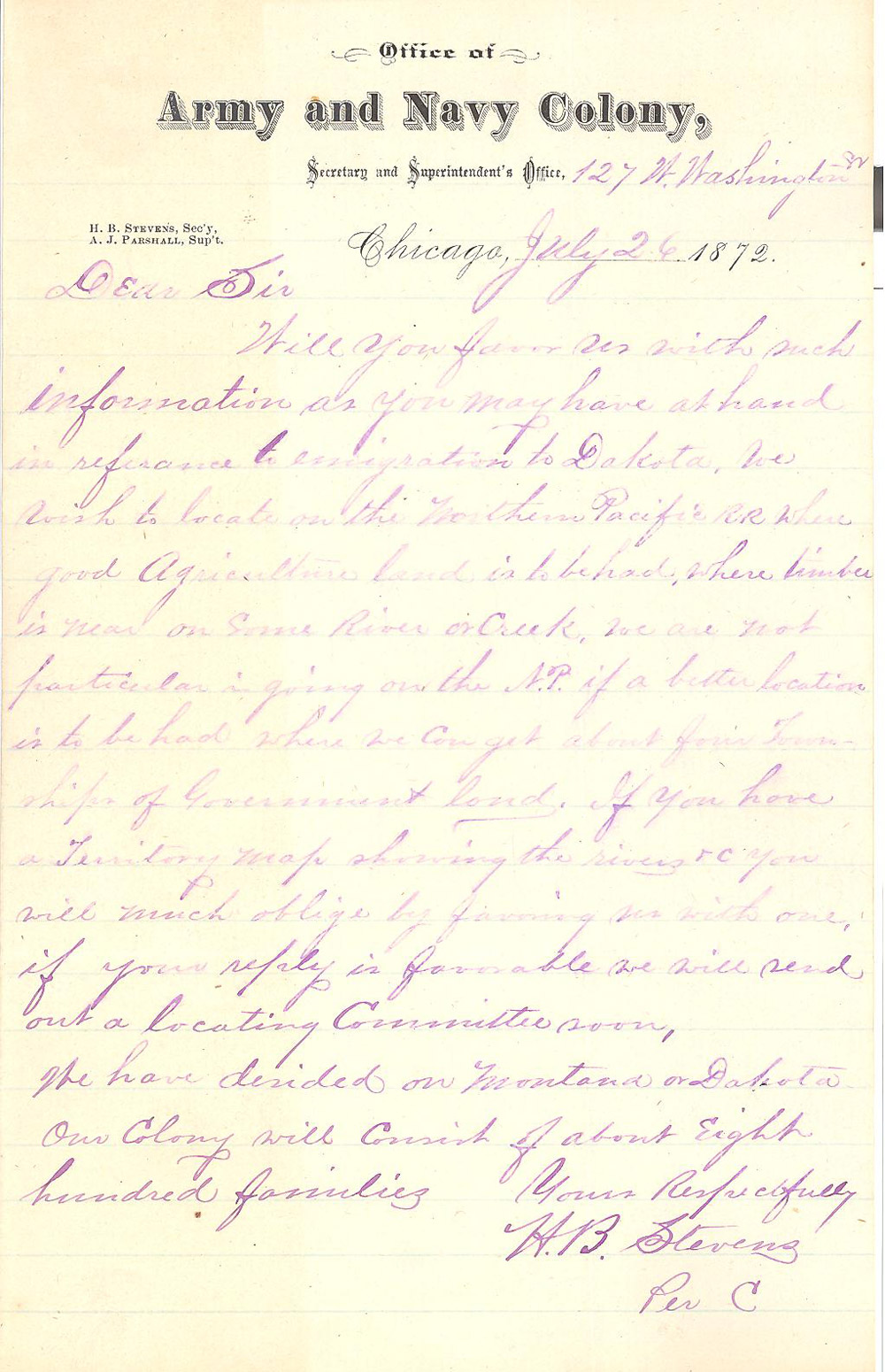

One of the important tasks of the territorial governor was to promote immigration (sometimes written as emigration) to the Territory. In those days, people wrote many letters because there were no telephones or computers. The governor’s office frequently received letters from organizations that wanted more information on crops, weather, land, and markets. (See Document 3) Individuals wrote to find out what kind of opportunity they might have for farming or other work. (See Document 4) The following letters show us that people all across the United States had an intense interest in Dakota Territory.

Document 3

Office Army and Navy Colony, Secretary and Superintendents Office, 127 W. Washington St. Chicago, July 26, 1872

H. B. Stevens,Sec’y

A. J. Parshall, Supt.

Dear Sir

Will you favor us with such information as you may have at hand in reference to emigration to Dakota. We wish to locate on the Northern Pacific RR where good Agricultural land is to be had, where timber is near on some River or Creek, we are not particular in going on the N.P. if a better location is to be had where we can get about four townships of Government land. If you have a Territory map showing the rivers etc you will much oblige by favoring us with one, if your reply is favorable we will send out a locating Committee soon,

We have decided on Montana and Dakota Our colony will consist of about eight hundred families.

Yours Respectfully

H. B. Stevens, Per C.

[Governor Burbank answered this letter on August 2]

[Mr. Arthur J. Parshall (b. 1846), Stevens’ partner, was a veteran of the Civil War. In 1877, the acting Governor or Wyoming, George French, recommended him for an appointment as Register of Deeds for Custer County. Governor Pennington made the appointment and Parshall soon relocated to Dakota Territory with his wife Mary and their children.] SHSND Series 76, Box 1, File 18

Document 4

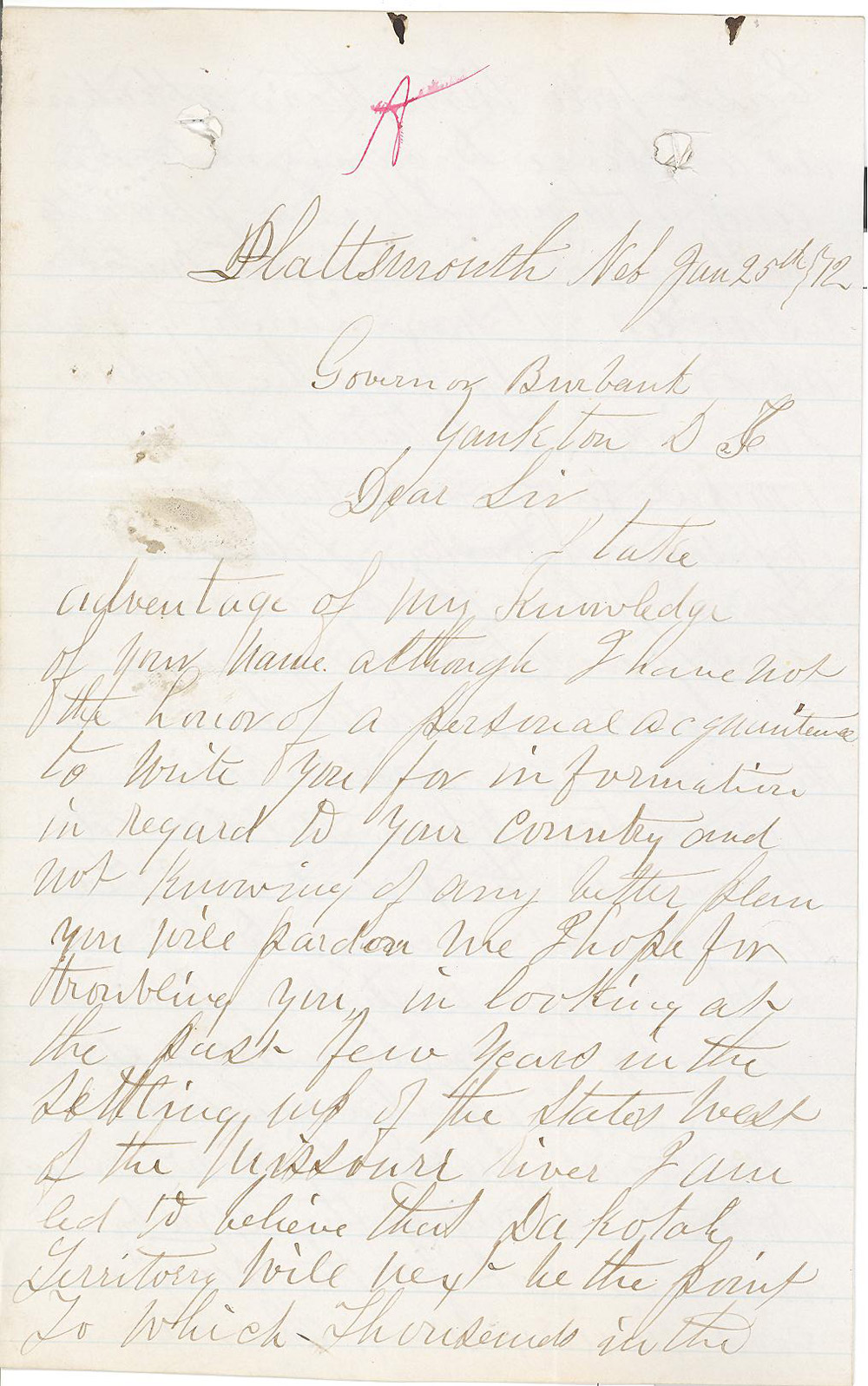

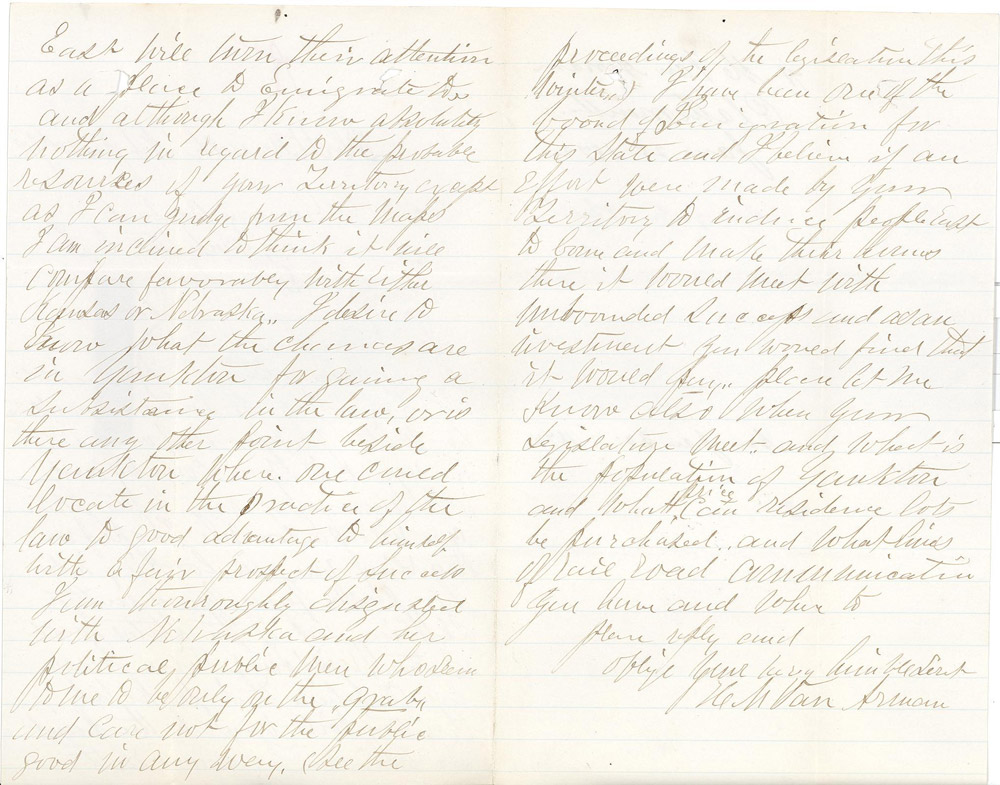

Plattsmouth Neb Jan 25th ‘72

Governor Burbank, Yankton, D T

Dear Sir,

I take advantage of my knowledge of your name although I have not the honor of a personal acquaintance to write you for information in regard to your country and not knowing of any better plan You will pardon me I hope for troubling you in looking at the past few years in the settling up of the states west of the Missouri River I am led to believe that Dakotah Territory will next be the point to which thousands in the East will turn their attention as a place to Emigrate to and although I know absolutely nothing in regard to the probably resources of your Territory except as I can judge from the maps I am inclined to think it will compare favorably with either Kansas or Nebraska. I desire to know what the chances are in Yankton for gaining a subsistence in the law, or is there any other point beside Yankton where one could locate in the practice of the law to good advantage to himself with a fair prospect of success.

I am thoroughly disgusted with Nebraska and her political public men who seem to me to be only on the grab and care not for the public good in any way. (See the proceedings of the legislature this winter) I have been one of the board of Immigration for this State and I believe if an effort were made by your Territory to induce people East to come and make their homes there it would meet with unbounded success and as an investment you would find that it would pay. Please let me know also when your legislature meets and what is the population of Yankton and what price can residence lots be purchased . . and what lines of Rail Road communication you have and where to

Please reply and

Oblige your very humble servt

M Van Arman.

[Governor Burbank responded to this letter on January 30, 1872] SHSND Mss 30076 File

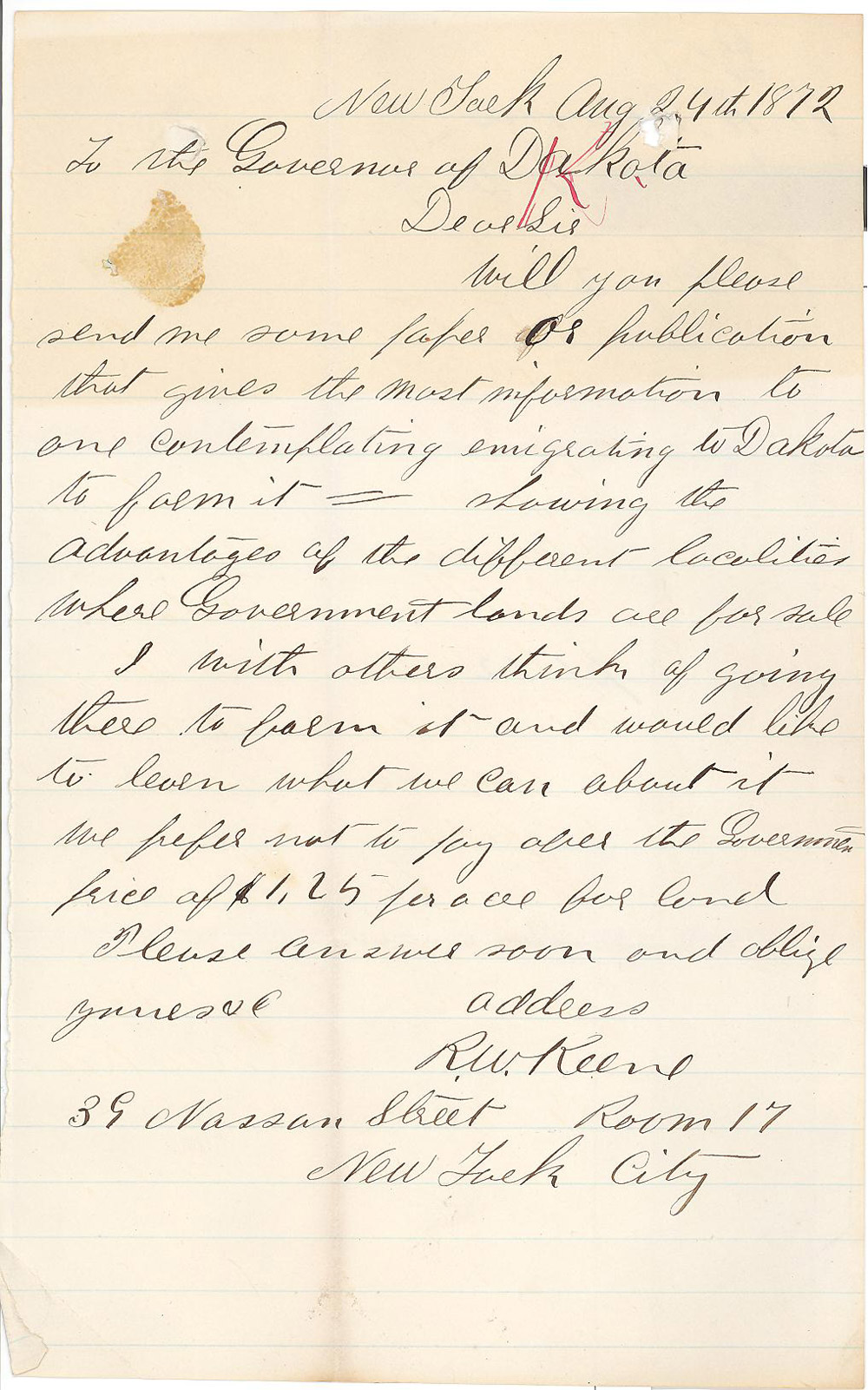

Document 5

New York Aug 24th 1872

To the Governor of Dakota

Dear Sir

Will you please send me some paper or publication that gives the most information to one contemplating emigrating to Dakota to farm it - - showing the advantages of the different localities where Government lands are for sale.

I with others think of going there to farm it and would like to learn what we can about it we prefer not to pay over the Governments price of $1.25 per acre for land Please answer soon and oblige your svt

Address

R. W. Keene

39 Nassau Street Room 17

New York City

[Governor replied on September 12] SHSND Series 76 Box 1 File 18

Document 6

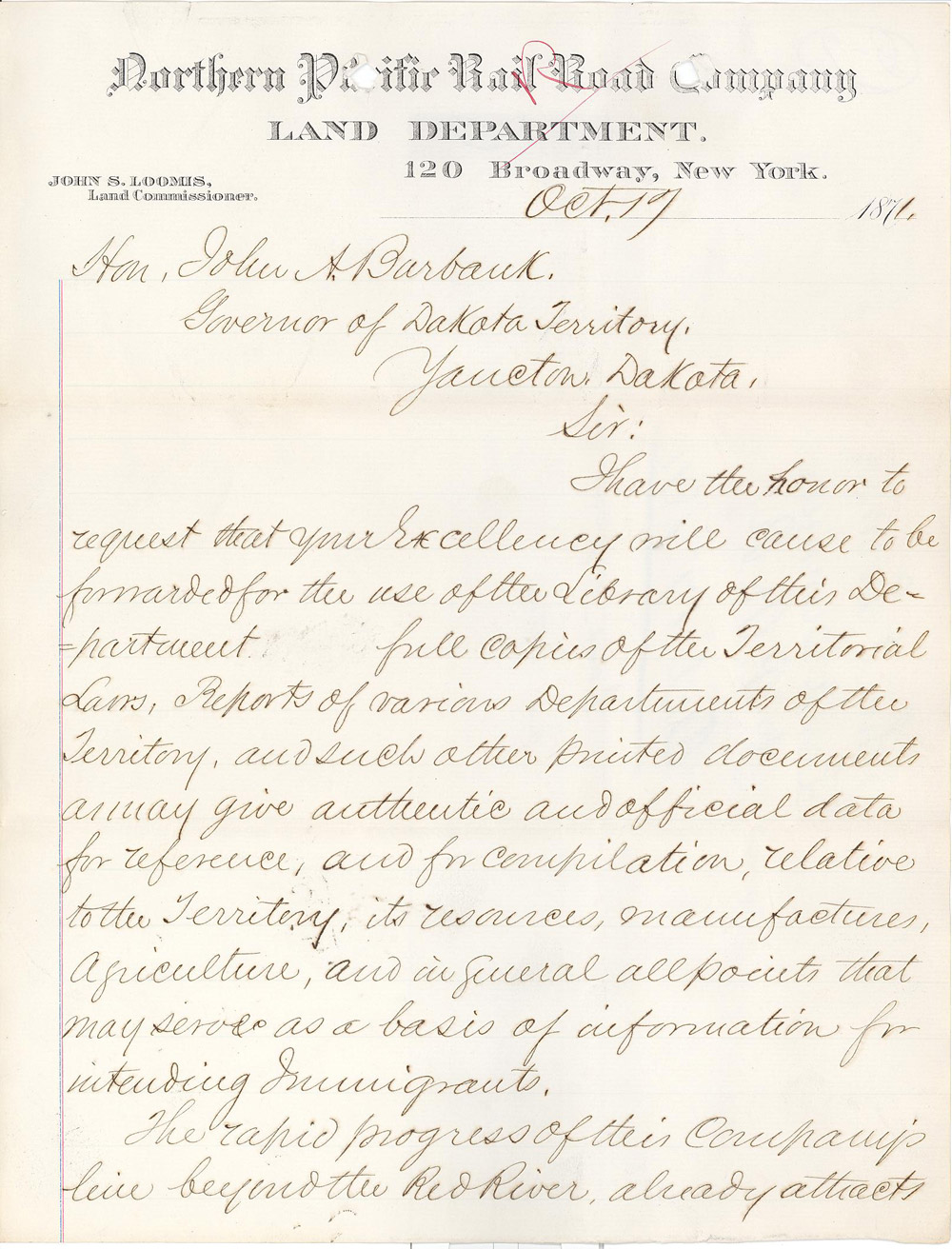

Northern Pacific Rail Road Company (letterhead)

Land department 120 Broadway, New York.

October 17, 187[2?]

John S. Loomis, Land Commissioner

Hon John A. Burbank,

Governor of Dakota Territory, Yancton, Dakota,

Sir: I have the honor to request that your Excellency will cause to be forwarded for the use of the Library of this department full copies of the Territorial Laws, Reports of various Departments of the Territory, and such other printed documents as may give authentic and official data for reference, and for compilation relative to the Territory, its resources, manufactures, agriculture, and in general all points that may serve as a basis of information for intending Immigrants.

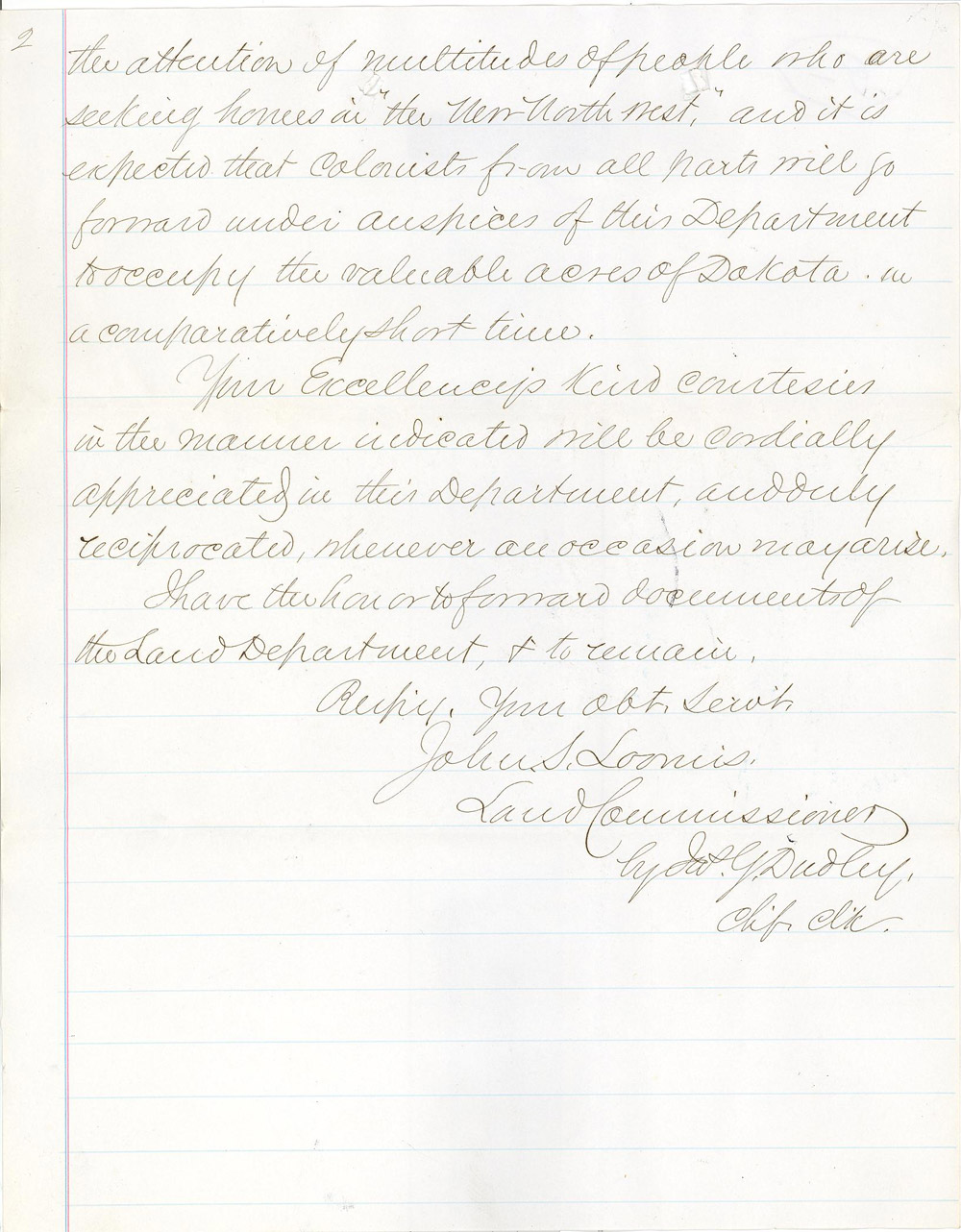

The rapid progress of this company’s line beyond the Red River, already attracts the attention of multitudes of people who are seeking homes in “the New Northwest,” and it is expected the colonists from all parts will go forward under auspices of this Department to occupy the valuable acres of Dakota in a comparatively short time.

Your Excellency’s kind courtesies in the manner indicated will be cordially appreciated in this Department, and duly reciprocated, whenever an occasion may arise.

I have the honor to forward documents of the land Department and to remain

Rspy, Your Obt. Sevt.

John S. Loomis

Land Commissioner,

By W. Y. Dudley

Chf clk.

SHSND Ms. 30076 File 18

Dakota was called the “New Northwest.” This name indicated to Americans of that time that Dakota was a place where farmers could find good land for farms and that cities would grow as they had in the “Old Northwest” which included Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin. (See Document 5)

The territorial legislature passed a law to open an immigration office in 1866, but the legislature did not have the funds to hire a commissioner of immigration. In 1869, Frank Bem took on the task. He and the commissioners who followed him corresponded with immigration organizations, wrote pamphlets in many European languages, and kept records of Dakota’s advantages. Though the literature of immigration sometimes exaggerated the benefits of life in Dakota, the effort was successful in bringing new settlers to the territory (and to the state) until the 1930s. The Northern Pacific Railroad also had an immigration department which encouraged settlers to choose northern Dakota Territory. (See Document 6)

Why is this important? Dakota Territory could not become a state (or two states) until it had reached a population of several thousand people. In order to increase the population, the territory worked to recruit new settlers from the United States and Europe. Under Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution, immigrants could follow procedures to become citizens. The 14th Amendment, adopted in 1868, guaranteed immigrants the protections of the Constitution even before they had become citizens. Encouraging new settlers to come to Dakota Territory was a difficult task because there were few railroads and great uncertainties about American Indian land claims.