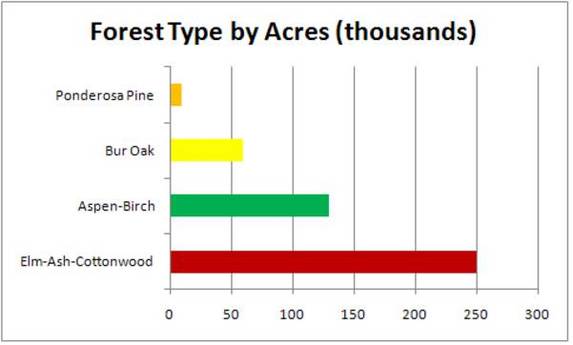

By definition, the Great Plains has few trees. Therefore, we can expect that the pine tree forests of North Dakota are pretty small. (See Image 1) But, for a few years, the U. S. Forest Service designated a portion of one township in Slope County as a national forest.

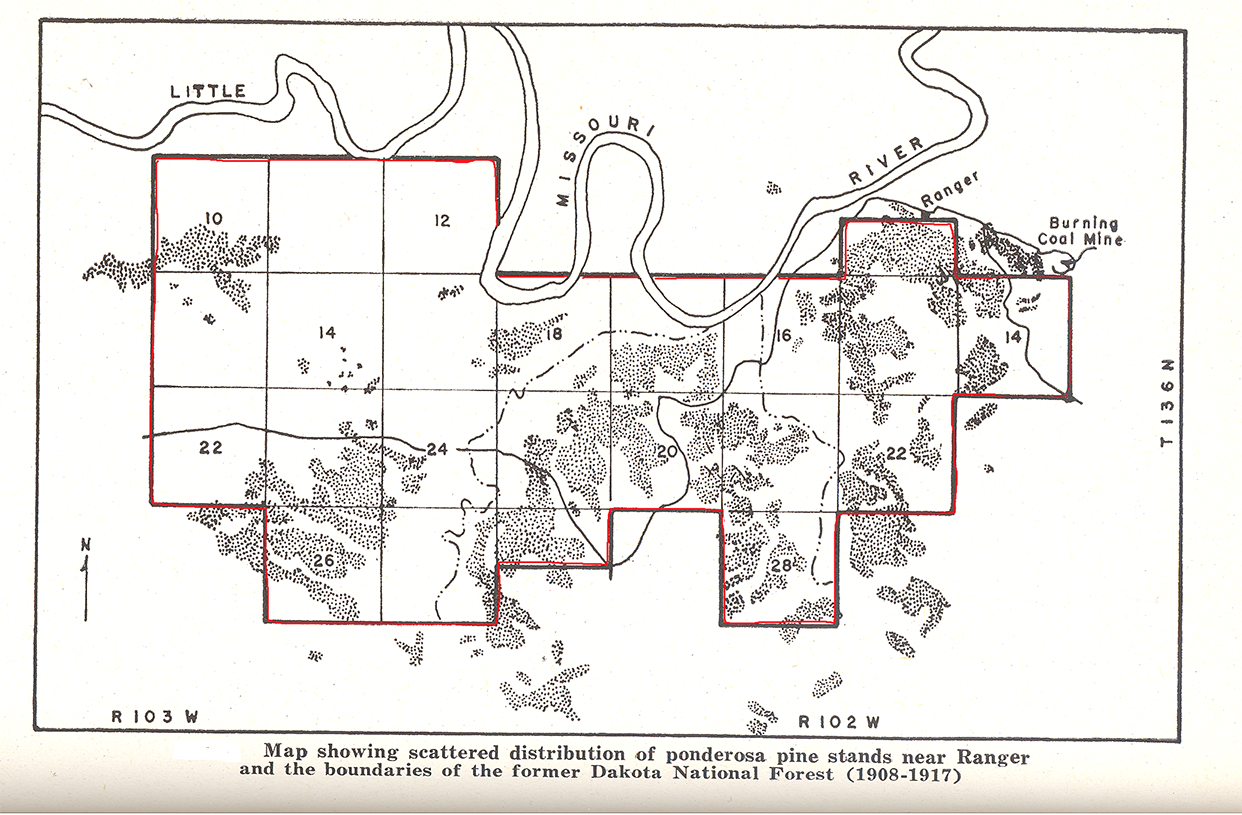

Ponderosa pines are uncommon in North Dakota. Of the 4,328 acres of ponderosa pine in North Dakota, 3,908 acres are in Ranger Township in Slope County near the Little Missouri River. For many years, settlers used the pines to build houses and barns. Some people traveled as far as 75 miles to harvest timber for their buildings. (See Image 2)

The Northern Pacific Railroad (NPRR) also used pine logs for railroad ties. In 1877, Eber Bly of Bismarck operated a saw mill near Ekalaka, Montana, where he cut trees into railroad ties for Northern Pacific. Bly’s crews cut the trees at the Logging Camp (section 21 in Ranger Township) south of Medora. The logs were cut into ties at Ekalaka, then floated north on Cottonwood Creek and the Little Missouri River to Medora for the Northern Pacific Railroad. Mr. Bly’s plan to supply the railroad with ties for track-building ended when Indians unintentionally scared the railroad workers. The crew left the river’s edge and abandoned the ties. The NPRR decided it was more efficient to bring ties from Minnesota. However, the pine ties found another use. Settlers in the Medora area, including Theodore Roosevelt, retrieved the abandoned ties from the river and used them in construction.

North Dakota state officials gave some thought to protecting the pines in Slope County. Finally, Governor John Burke alerted the National Forest Service to the presence of the small pine forest in southwestern North Dakota. In June, 1908, the Forest Service sent a forester to study the trees. The forester reported that some of the pines were as tall as 75 feet. The forest was not dense, and lumber companies would have little interest in the pines. Though some of the burning coal veins had set the grass on fire, there was no evidence that the trees had burned. Porcupines, however, had damaged 25 per cent of the trees.

On November 24, 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt declared the forest in 22 sections (14,080 acres) of Slope County to be the Dakota National Forest. (See Map 1) Settlers had already claimed some of the land within the forest boundaries. The National Forest Service hired a rider who kept cattle off the public land, and a post office was established in Ranger Township in section 10.

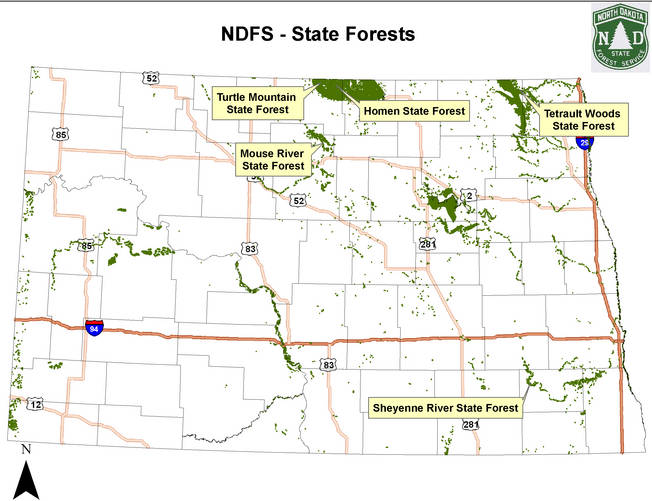

Governor Burke was interested in planting shelterbelts (rows of trees on the edges of farm fields) around the state. He thought the ponderosa pines would be good trees for that purpose. In 1912, the government established a tree nursery near Deep Creek where the foresters obtained water to irrigate the trees. (See Image 3) Pine seedlings were taken from the nursery and planted in fields. However, the trees failed to thrive. The Forest Service considered the experiment unsuccessful.

The high cost of taking care of the nursery was another problem. The Dakota National Forest was isolated and provided few trees that could be cut and sold to timber contractors. So, on July 13, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson signed a proclamation that ended national protection for the Dakota National Forest. Following the proclamation, the land not owned by the NPRR was opened for settlement. (See Map 2)

Why is this important? The Great Plains is defined as a level, treeless grassland. However, in some places, mostly along creeks and rivers, there are enough trees to support construction. Settlers, the Army, and some businesses used the trees for houses, barns, fence posts, corrals, railroad construction, and fires for cooking and warmth. If these people had to buy wood, the costs would have been very high because the wood would have been transported for hundreds of miles.

The ponderosa pines contribute to the biodiversity of this land. The trees shelter birds and mammals, provide food (pine nuts), and absorb moisture that would otherwise run off the land. Three birds of North Dakota prefer the pine forests of Slope County. The red crossbill and the white-winged crossbill have beaks adapted to pulling pine seeds out of the cones. The common poorwill nests on the ground; it prefers the habitat of the plants that grow near ponderosa pines.

Today some of the land that was once part of the Dakota National Forest is protected as part of the National Grasslands which is administered by the National Forest Service.

National Forest Service on ponderosa pines in North Dakota: http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/fhm/fhh/fhh-03/nd/nd_03.pdf