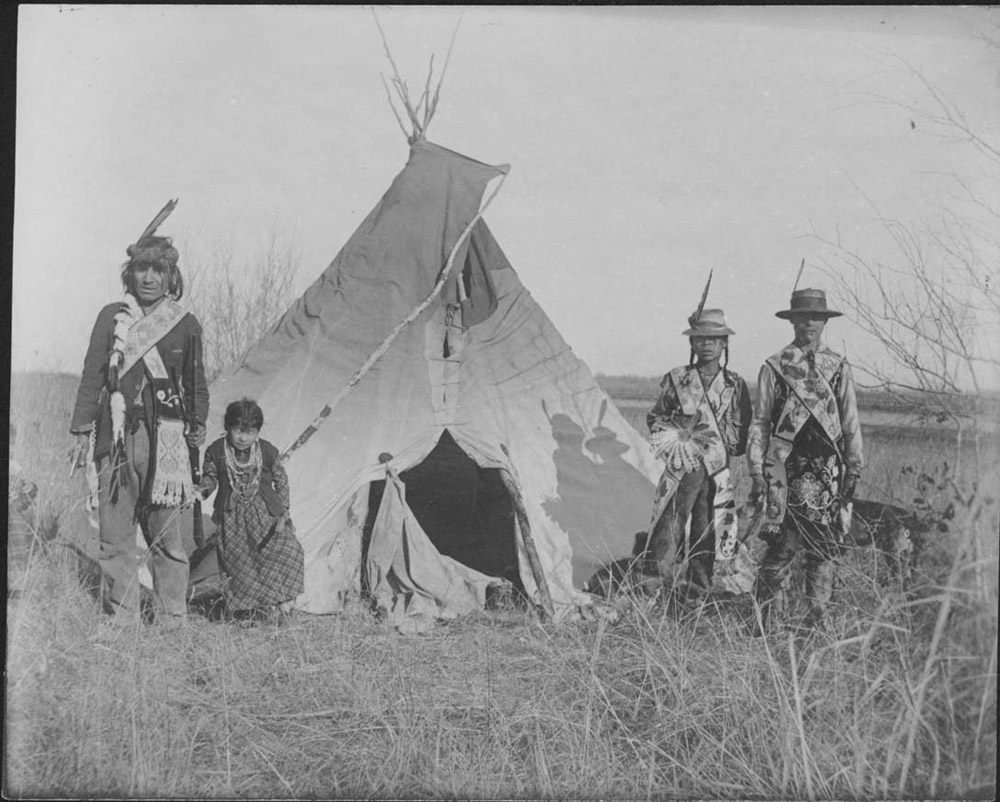

Unlike the other tribal communities of North Dakota, the Turtle Mountain Chippewas include a mixture of cultures with a common history. There are people whose family roots are in the Chippewa (Ojibwa) or the Cree (a Canadian tribe) tribes. There are also many people of Turtle Mountain who are descended from a Cree or Chippewa ancestor who married a French or Scottish trader in the 18th or 19th centuries. These people are the Métis. (See Image 1.)

In the 1700s, the Chippewas moved into northern Minnesota from previous homes along Lake Superior. They were already engaged in the fur trade business. Part of the motivation to move farther west was to find more fur-bearing animals and to trade at the growing number of fur-trade posts in the Hudson’s Bay drainage. However, the Chippewas occupation of northern Minnesota was often blocked by Dakotas who also lived in the northern woodlands.

By 1789, the Chippewas lived primarily just east of the Red River Valley. To the west, across the Red River, the Dakotas controlled the open country. By the end of the 18th century, the Chippewas (historically called the Saulteaux) had moved into the southern Red River Valley and were beginning to trade furs near Pembina. Though the Red River Valley was considered a “road of war” and not permanently occupied by any tribe, it was rich in game and attractive to the Chippewas. The Chippewas ranged as far as the Rocky Mountains in their efforts to participate in the fur trade.

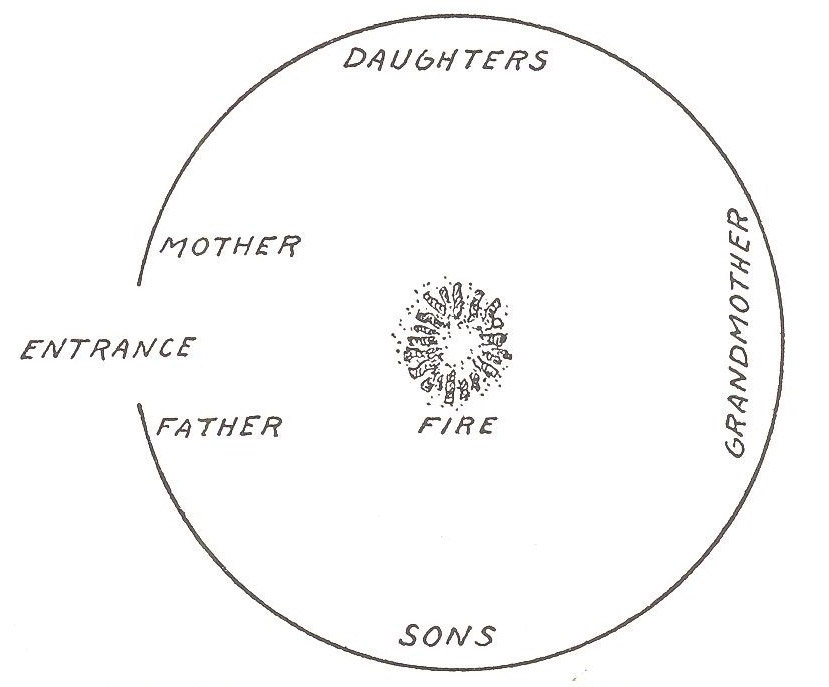

Fur and bison hunting became a way of life for the Chippewas. As they adapted to life on the Plains, they also “borrowed” some customs of other tribes such as hide-covered tipis and the Sun Dance. (See Image 2.) They acquired horses for travel and hunting. As they went through these adaptive processes, the tribes came to be known by new names. Some Chippewas who lived on the Plains called themselves Bungi. Non-Indians called them Plains Chippewa or Plains Ojibwa.

The clothing of the Turtle Mountain Chippewas reflected their diverse cultural heritage. Women borrowed the clothing style of non-Indian women, but they decorated their cloth dresses with designs worked with beads or dyed porcupine quills. Métis men wore a hooded coat called a capote that was made from a Hudson’s Bay blanket. The coat was wrapped with a distinctive, brightly colored woven sash. Most men and women wore soft leather moccasins that were decorated with floral beaded or quilled designs. Their moccasins were of a distinctive style with a puckered toe. Sometimes, the Chippewas were called “the people of the puckered moccasins.”

Children of the Chippewa family called their father and his brothers “father.” Children called their mother and her sisters “mother.” All of these relatives participated in protecting, raising, and educating the children. (See Image 3.) Children belonged to the clan of their father and stayed with that clan throughout their lives. A young person could not marry a person of their own clan. However, members of clans lived in different villages, so when Chippewas traveled, they would be welcomed by members of their own clan wherever they went. Clan membership was passed from father to child, but French or Scottish fathers of Chippewa children did not belong to a clan. Therefore, Métis children did not belong to a clan unless a Métis woman married a Chippewa man who passed clan membership on to his children.

Plains Chippewa communities were organized into bands that included several families. People could leave one band and join another if they saw an advantage in doing so. Each band was named for its leader. Leaders usually inherited the position, but could not keep the position if they did not provide well for the people of their band. The leader had assistants and looked to the council for advice. A group of men was assigned the role of maintaining order. Métis bands chose to follow a similar community organization.

Though the Plains Chippewas adopted a Plains lifestyle, they maintained their old religious views. Their sacred spirit was Gitche Manitou (GIT chee MAN ih too). The Chippewas participated in ceremonies to encourage Gitche Manitou to help individuals or the entire band. Many Métis chose to follow the religion of their French fathers and became Catholic Christians.

Why is this important? Between 1200 and 1860, many of the Indian tribes of the Great Plains organized into groups with similar languages and cultural characteristics. However, the tribes continued to adapt as they moved from one place to another. Trade and social encounters brought new ideas and new customs to each tribe. The Chippewas moved from the woodlands to the Great Plains and changed their customs to match their new way of life. When the Chippewas intermarried with European fur traders, a new cultural group, the Métis, emerged. Every community of Plains Indians changed when it was right to do so, but retained important parts of their cultures that helped them move forward with their lives.