During the decades before 1650, Lakotas, a branch of the large Dakota (sometimes called Sioux) nation, lived in the woodlands east of the Red River. During the 17th century, they moved into the Great Plains and occupied the land between the Red River of the North and the Missouri River. They began to live a more nomadic life than they had in the woodlands. They followed bison herds and became expert hunters.

According to the winter count of Battiste Good,Battiste Good was a Brulé Lakota who lived on the Rosebud Reservation. His Lakota name was Wapostangi, or Brown Hat. His winter count is featured in the Smithsonian Institution exhibit on Lakota winter counts. Battiste Good’s winter count is based on an oral history that extends back to 900 A.D. the southern bands of Lakotas first saw horses around 1700. By 1715, horses appeared frequently in Good’s winter count. Sometime in the middle 18th century (around 1750), Lakotas used horses regularly for hunting and transportation. Most likely they traded with other tribes for horses as they found out how useful horses could be.

Horses became an important part of Lakota society because Lakotas were nomadic. Lakotas moved their villages to places where they had good grass and water for their horses, and nearby bison herds. Horses made moving the village much easier because they could carry a heavy load. Horses also made bison hunting more efficient because a horse could carry a hunter very close to the bison herd.

A Lakota family might own several horses, but a bison hunting horse was a special animal that was not used for other purposes, except perhaps war. When a man wanted a hunting horse, he selected a fast young horse and trained it to hunt bison. He would ride the horse alongside and into herds of running horses. In this way, the horse became trained for speed and learned how to approach a moving herd of animals. The hunter also rubbed bison robes over the horse so it would learn to know and not fear the smell of bison.

Some hunters rode after the bison herd with only a halter on their horse. Others used a saddle as well. When a Lakota horse was prepared for a bison hunt, it had a halter, or head piece, that was made of leather tanned from a bison hide. There were two leather straps: one strap encircled the horse’s muzzle just behind the corners of the mouth. This strap was attached to another strap that passed behind the horse’s ears. Another long leather strap was attached to the halter and extended back to the rider. The halter fit somewhat tighter than modern halters.

Older men and boys sometimes used saddles in the bison hunt. (See Image 2.) The saddle was made from two pieces of wood, about 20 inches long and one and one-half inches thick. The two pieces were joined by an elk antler that was shaped and fitted to form an arch just behind the horse’s withers. Another piece of elk antler joined the two pieces of wood behind the rider. Raw bison hide covered the entire saddle and was stitched into place with sinew. (See Image 3.) When the rawhide dried, the wood and antler saddle was very strong. The saddle was attached to the horse with a girth of bison leather. Some hunters made stirrups of buffalo hide or wood. (See Image 4.) These well-made saddles might have been used by generations of Lakota hunters.The Lakota saddle was strong and comfortable for long journeys. It was a secure mount in warfare. The U.S. Cavalry adapted the Lakota saddle for its cavalry horses. The Army called the new design the McClellan saddle.

A woman’s saddle was made in a similar way, but constructed so that the woman could also carry large packs of household goods or children on horseback. (See Image 5.)

Some Lakota horses were used to pull loads packed onto a travois (TRAV-wah, or TRAV-voy). (See Image 6.) A travois was made using tipi poles which were inserted into a harness placed over the horse’s back. A webbed basket was suspended between the poles for carrying children, elders, or ill adults, household goods, or bison meat. Before horses came to the northern Great Plains, dogs pulled much smaller travois. (See Image 7.) A woman who could pack a travois efficiently and well was held in high esteem.

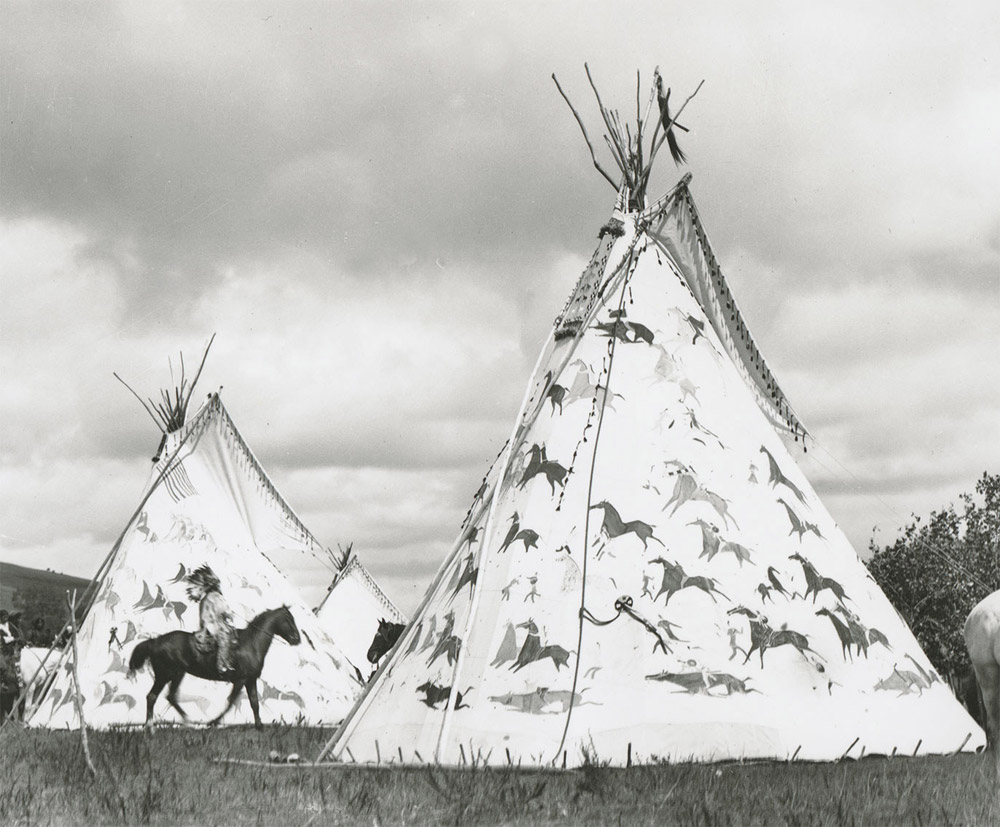

Horse hair had many uses, too. It could be removed from the mane or tail without hurting the horse and might be used to decorate a headpiece or clothing. Horse hair was also added to bison hair in making very strong ropes. (See Image 8.) Lakota artists often used images of horses in painting or beadwork. (See Image 9.)

Lakotas loved and cherished their horses. For special occasions (religious ceremonies or war) a horse might be painted with symbols that were important to its owner. (See Image 10.) Some people decorated their horse’s bridles, saddles, and saddle bags with beads or quillwork. (See Image 11.) One mask (in the Smithsonian Institution today) was made of bison hide. Holes were cut in the hide for the horse’s eyes and ears. The hide was decorated with feathers.

Horses came to represent wealth to the Lakotas. Both men and women could own horses. Men might acquire horses through trade or in raids. A woman might receive a horse as payment for her beadwork. But, in the Lakota tradition, wealth was to be given away to honor someone else who had done a great deed, or to honor someone who had died. Horses often changed hands in giveaway ceremonies.

Why is this important? Historians debate the impact of horses on the Lakota way of life. Some historians argue that horses changed the Lakota way of life and even had an impact on their religious ideas. Other historians state that horses allowed Lakotas to improve, but not change, their way of life. The Lakota economy–or way of making a living–did not change greatly when they acquired horses. Lakotas continued to hunt bison and incorporate the great animal into every aspect of their lives. Because horses made bison hunting so much more efficient, they, too, came to be honored in many parts of Lakota life. Once the bison were gone from the northern Great Plains, horses remained with the tribe to connect the Lakota people to their pre-reservation past.