Telephone Introduction

J. L. Grandin purchased two telephones when he saw Alexander Graham Bell’s new invention at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. He brought the phones, the first in northern Dakota Territory, to his bonanza farm and used them to connect two farm offices. A few other telephones connected some towns over the next few years, but Bell’s patent made telephones too expensive for most private homes until 1894.

By 1905, small “farmer lines” connected some communities around North Dakota. (See Document 1.) Farmers worked together to erect the poles, string the lines, and wire the houses on their line. The initial cost was low, but residents seldom paid for maintenance. Any number of phones could be connected on the line, and the residents of every house could listen in on every call. These were “party lines.”

Document 1. Pauline Olson’s Diary

Pauline Olson lived on a farm near Bottineau. For more than 30 years, she made daily entries in her diary. In October, 1954, Olson wrote a short history of her phone line. Though she found the phone useful, it seemed to her that when the phone rang, it was more likely to be bad news than good news. The Olson’s first phone was on a “farmers’ line.” Each family along the line paid for installation and the telephone “instruments.” They kept that phone (probably a magneto “cranking” phone) until they got the new REA co-op phone line in 1954. She was a little disappointed when the new phone was replaced six years later. After all, her first telephone and telephone company had lasted nearly 50 years. She attributed the poor quality of her first phone line to inadequate service by the linemen, but it was likely that the local exchange could not afford maintenance costs.

Oct 1954 Phone Report

I shall here. Again write of another Episode. This time the Phone. The first Phone we had on my home at Krogen was built by the farmers & they payed for the Poles & Phone instruments – And that what was called Farmers TelePhone co. They started to build that in 1905 I know it was finished at Harvest time and We Jake & I when we came down here from proving up our 40 a[cres] we moved the house from there to this place in 1909 - & then we bought our Phone & share from Gust Lubeck. And in all them years we had this Phone. But today Oct 18 – I took the wire off & so the Last of Farmers line is a writen off past. Now we expect to get our dial Phone in soon See a new Co. is now started as the old line went broke could not keep it up too many lazy line men who was payed good wages but never did fix any thing. So Good by past. Good Old Phone line that given me much company & many Sad reports. To many Sad things been told to me many more then Happy reports. I was the one who disconnected the Last line our 1905 farmers line. Good by. Yes Oct 19 our Dial Phone is Set in our House The new episode starts Will I see the end of this

[Next page – added later] . . . now 1960. . . Sad things been more then was all the passed years. Told over this new Phone when you read in the book nothing but sad reports

Yes This ended This new Line built in 1954. Now its sold to Bell Co. And Oct 27 – 1960. Bell put in a new Phone. And so 6 years only did we keep this Line.

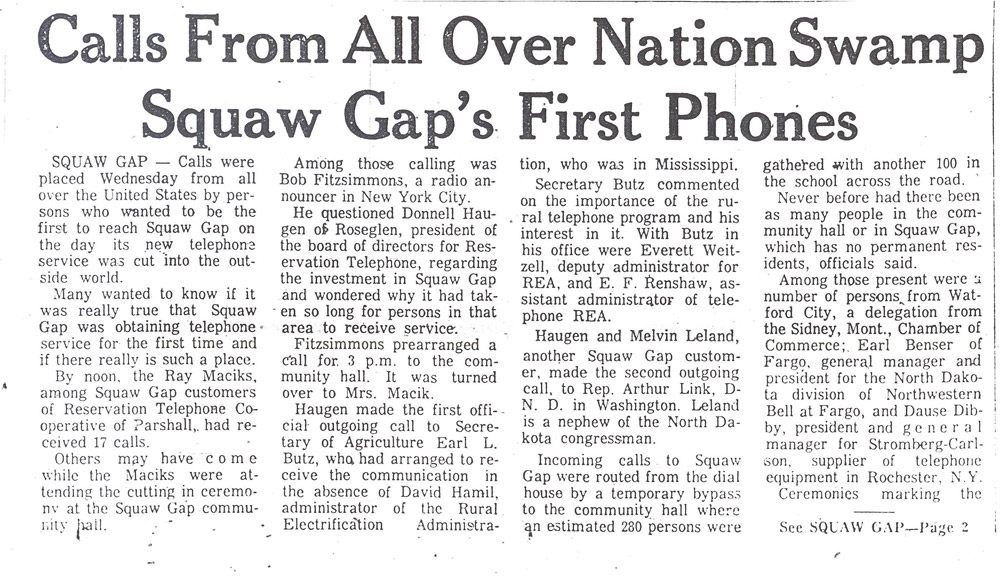

When the phone lines were improved, they were connected to “central” which was the place where switches connected a caller to a specific phone. (See Image 1.) Central was managed by an operator who actually made the connections. The operator was most likely a woman who worked at a switchboard in her home. Central served as an important information source. The operator could locate the doctor or sheriff. She relayed burglar alarms (bank alarms were sometimes wired to the central switchboard.) Central could also put out a general ring and make announcements, such as a fire call, to all households. If the switchboard was in a private home, telephone service would be available 24 hours each day. If it was in a different building, service would only be available when the operator was on duty.

By 1953, only one-half of North Dakota’s rural homes had a telephone. Fewer than one-fourth of rural homes had adequate telephone service. Lack of maintenance meant that, by 1940, phone service was deteriorating. City residents had dial phone service, but rural North Dakotans were unlikely to have any service. Many of the “farmer lines” did not connect to Northwestern Bell Telephone service, so they could not call outside of their own community.

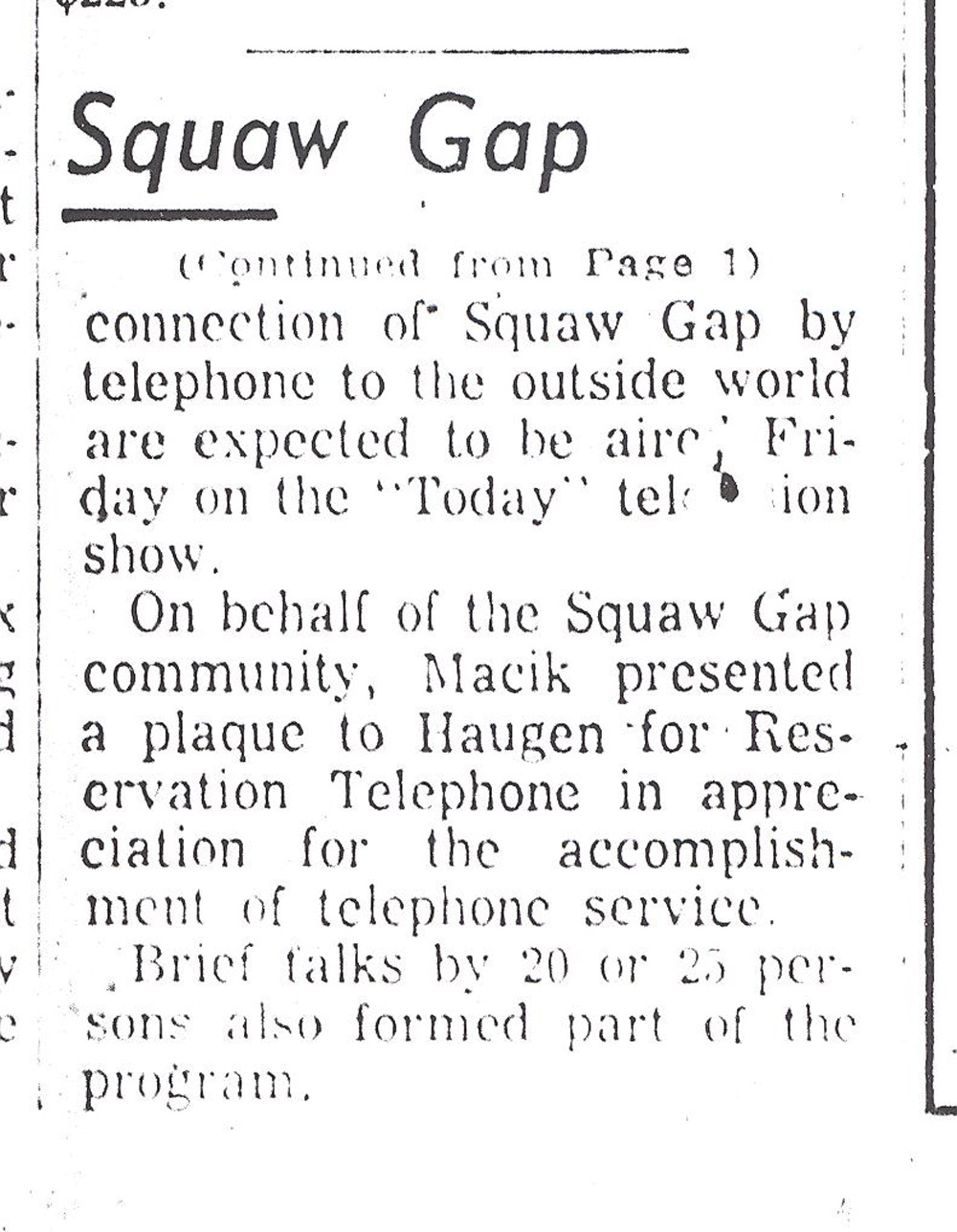

By 1950, there were 120,000 telephones in North Dakota. Seventy-five percent of those phones were in cities. (See Image 2.) The rest were in rural homes that connected to one of the more than 800 small telephone companies in the state. Phone service was localized and poorly maintained.

In 1949, Congress amended the Rural Electrification Act of 1936 to make telephone service part of the Rural Electrification Administration (REA). The law made it possible for rural telephone cooperatives (co-ops) to borrow money for construction of new lines at two per cent interest. The REA sent two teams to North Dakota to assess the possibility of setting up telephone co-ops. Though their first impression was negative, North Dakota’s two senators, William Langer and Milton Young, supported the rural telephone program.One of the REA men was Mr. Colburn. He set out one spring day to visit with Oliver Sund in rural Stutsman County. His car got stuck in the mud and he had to walk four miles to find someone to pull him out. He returned to Cleveland and called Chester Graham, the Farmers Union executive in charge of the telephone project. Chester Graham called Oliver Sund’s brother-in-law who managed to drive through the mud to Sund’s house and bring Oliver to Cleveland. Talking by telephone to Graham in Jamestown, they agreed to set up a meeting the next day with Sund, Graham, Senators Langer and Young, and Mr. Colburn.

Later that day, Chester Graham took Mr. Colburn for a drive toward Carrington. He wanted to meet some co-op members, but before they reached Carrington, Mr. Colburn suddenly said, “It can’t be done. It just can’t be done. ... You can’t have rural telephone in North Dakota. You’ve got to have people before you can have rural telephone.”

Senators Young and Langer informed Mr. Colburn that the REA rural telephone program was for all the people, not just people with good roads. Mr. Colburn, by all accounts a very nice man, was replaced by an engineer who accepted the challenge and got the co-ops started.

The rural telephone co-ops began to organize, often around the same communities as the rural electric co-ops. The first telephone co-op was Dickey Rural Telephone Mutual Aid Co-operative in November 1950. But there were more obstacles to face. The greatest of these was funding. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) was the administrative home for REA. The USDA had applied for $50 million for the rural telephone program, but the first wave of applications totaled more than $100 million. Co-ops in North Dakota requested $25 million.

In April, 1953, 13 North Dakotans traveled to Washington, D.C., to urge Congress to provide greater funding for the rural telephone project. Mrs. Roland Erman of Heaton addressed the Senate Agricultural Appropriations committee:

Our one and only telephone is located in the Heaton grocery store three and a half miles from my home and is only available during store hours. . . . we [want to] be connected with the rest of the world so as to adequately insure us of protection for health and safety and participation in community life and to aid in more adequately carrying out our farm operation.

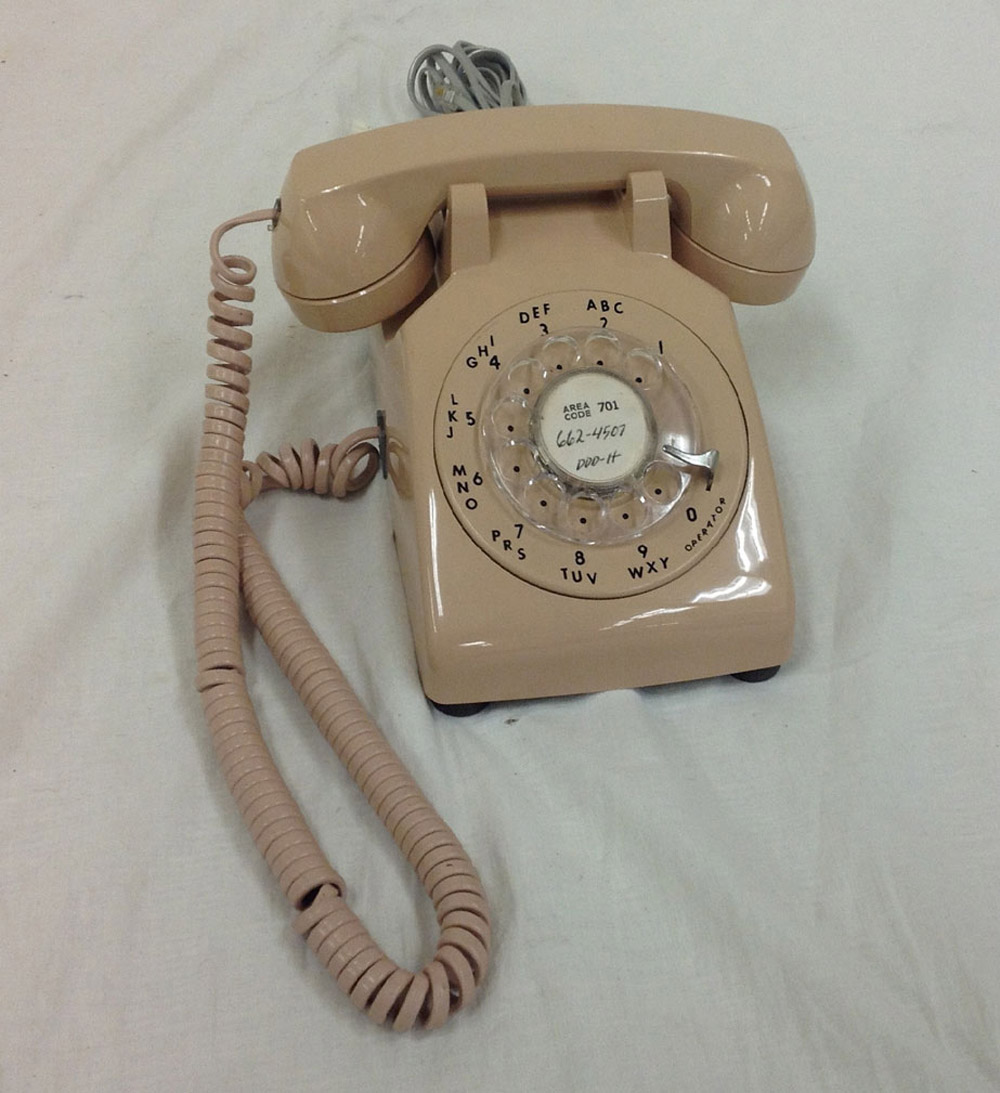

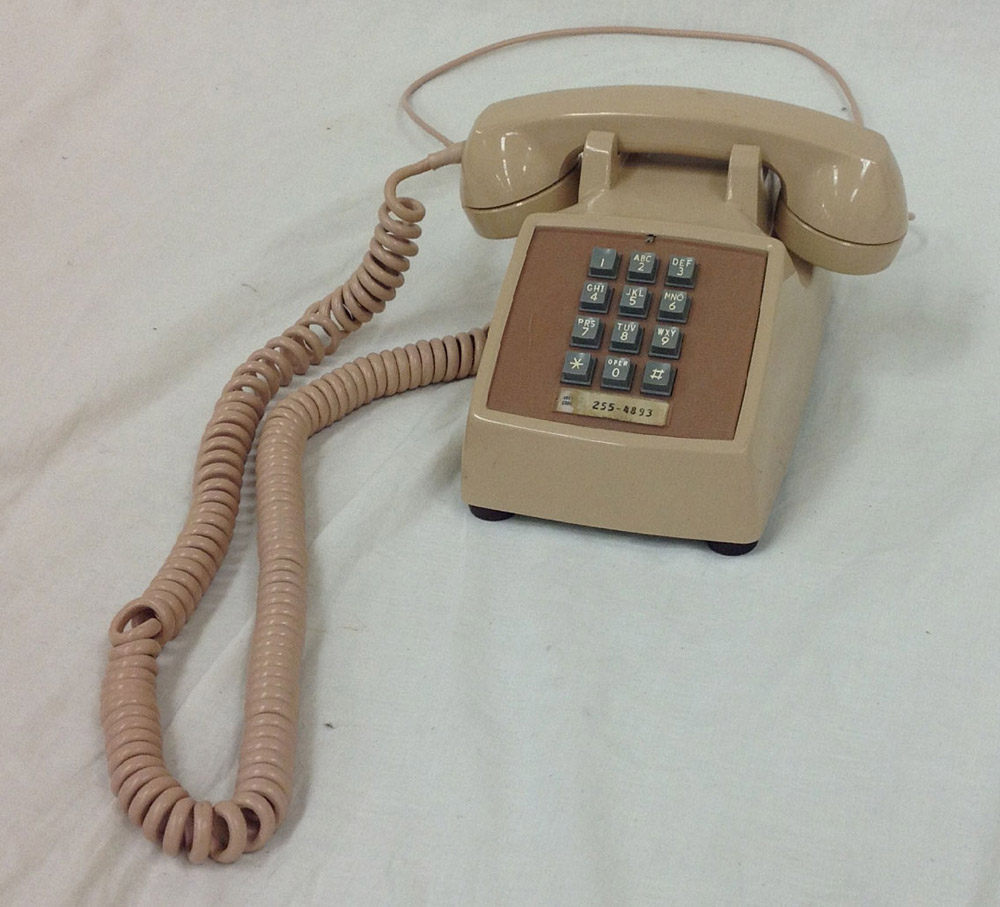

When the money became available, the co-ops began to build. (See Document 2.) The first telephone exchange to begin operation was Reservation Telephone Co-op located in New Town. (See Image 3.) Dial telephones on eight-party lines went into service on June 3, 1954. (See Image 4.) Dial phones did not require an operator, but users had to remember the numbers of the people they wanted to call. By 1964, all the telephone co-ops were in service.

Document 2. A telephone lineman’s memoir

Alex P. Nelson was a young man when he journeyed to North Dakota to become a lineman for a telephone company. He started work as a groundman, or “grunt” – one who dug holes for telephone poles. He later learned to be a lineman, one who climbs the poles to string wire or make repairs. This was a relatively new occupation in the 1920s, but one that had a good future for a young man. Much of the work was done by hand, rather than by machine. His work connected new farm and town phones on community phone lines that were installed before REA telephone co-ops.

“. . . I was assigned to dig holes. For digging I was issued a “banjo” which was a nine foot straight-handled shovel. To remove the dirt from the hole I was given a “spoon,” another long-handled shovel but with a curved blade. My first hole was to be six feet deep and about eighteen inches wide. What a project! By noon I was almost in tears and had dug down about four feet. My clothing was wringing wet and large blisters had formed on the palms of my hands. The noon break was more than welcome and after dinner I resumed my assignment with new zest. Finally the hole was finished and I gathered my tools together to move on to the next one. The foreman approached me and I expected to be scolded for having fallen behind the other workmen. But my spirits rose when he smiled and said, ‘Good going!’

. . .

“As a groundman my goal was to become a lineman. What an exhilarating occupation! It was a test of nerve, agility, strength. With it was the challenge of height and most important, keeping your cool.

“Anyone who has never climbed a pole with climbers, or as we called them, “hooks,” cannot know the beginner’s fear of moving upward on a smooth pole. The only deterrent between him and a crash to the earth was two small points of steel called “gaffs,” jabbed into the pole and supporting his weight. A knot in the pole or miscalculation on the climber’s part could cause him to “burn” the pole. Burning a pole means that when the hooks have slipped away from or broken out of the pole, the climber would smash to earth with shattering force. While falling, he’d desperately try to slow his descent by hugging the pole. This would result in flesh burns or slivers and splinters from the pole lodging in the arms and body. Then there was even the greater dread of having the hands slip off the pole and falling backward to the ground. This could mean a broken back or neck.”

. . .

“Almost six months after starting work I had my first opportunity to climb poles. It was a cold day in November with a thirty mile an hour wind out of the north. Rain the previous night had turned to sleet and then to snow. A good half inch of ice glazed the north side of the poles. Two other groundmen had been given their first opportunity to try climbing. There was an urgent need for extra linemen due to many wire breaks caused by the sleet or ice weighing down the wires. The two soon gave up. Actually, they were so frightened that the poles shook from the quakes. That evening, after a chat with the foreman, they resigned and left the crew. I felt it was a bit unfair to them, having their first challenge to climb poles under such adverse conditions.

Our foreman then asked me if I wanted a try at it. I said “yes” although I was almost in a faint from fear. I expected the climbers to cut out with every step I took. There was a strong urge to hug the pole but I knew moving in close to the pole was a sure way to cause the climbers to break loose. Finally I reached the crossarm at the top of the pole. What a relief to feel something I could grip firmly! Somehow I managed to place my safety strap around the pole and hook it back to my body belt. It wasn’t easy as it meant releasing one hand momentarily from the pole and crossarm. The safety strap was used to secure me to the pole and allow the use of both hands for work. The strong wind made it difficult to keep my balance even with the safety strap attached. So I steadied myself with one hand and tried to work with the other.

. . . One pole I climbed leaned heavily from the strong wind. I climbed on the high side of the pole as I knew I was supposed to, but when up partways a strong gust of wind caught me by surprise and swung me around to the under side of the leaning pole and I plummeted to the ground like a falling rock. I was not hurt but a little humiliated and my anger was aroused. Sometimes it’s good to become a little angry and let off some steam. I stormed back up the pole and my nervousness and fear were forgotten for a while.”

Why is this important? Telephone communication made rural communities safer. People could call for help if they needed it. Parents could communicate with schools or other families that might be picking up their children from school. In addition, telephone service meant farmers could more efficiently sell their crops (they could call daily for commodity prices) or communicate with customers in distant locations. Telephone communication helped bring people together into a close-knit community.

Telephone at Squaw Gap

Not all areas of North Dakota were covered by telephone service by 1955, or even 1965, or even 1970. A 1,000 square mile area known as Squaw Gap, North Dakota (30 miles east of Sidney, MT, 50 miles south of Williston) did not have any telephone service until December 15, 1971. (See Document 3)

Squaw Gap was not a town, just a small community with a hall and a small school. Ranching families living in this area had wanted to join a telephone co-op for many years, but there were so few families in the area that neighboring telephone co-ops could not economically support a phone system for Squaw Gap.

While other farmers and ranchers in North Dakota were using dial telephones, the people of Squaw Gap used citizen band radios (CBs) to communicate. They used their CBs to contact Loran Line who ran a store in Sidney. Ms. Line relayed their messages by telephone to medical personnel, law enforcement, or the grain elevator. Though Ms. Line was cheerful about the arrangement, it was a slow and cumbersome means of telephone access. And when Ms. Line’s shop was closed, there was no communication at all other than the CB.

There were several problems that prevented Squaw Gap residents from having access to telephones. The wide-spread ranching community would need only about 100 telephones-not enough to cover the usual costs of installation and maintenance. In addition, the lines had to be built through rugged badlands terrain which raised the cost of line construction. Squaw Gap residents also wanted to have toll-free lines to Sidney, Montana. Though Sidney was the closest town (30 miles by gravel road) and the location of most of their business transactions, crossing state lines was difficult for a co-op.

Finally, with federal assistance, arrangements were made with Reservation Telephone Co-op. Poles and lines were installed. Every home was wired. The linemen rushed to complete the job before winter cold made it impossible, and the connections were completed by December 15, 1971. In some places there were 10 miles of lines between phones. The Squaw Gap line cost $4,300 per subscriber, about seven times the national average for rural telephone service. Squaw Gap telephone subscribers paid a higher rate to help cover these costs, and all calls to any phone outside of Squaw Gap was a toll call. The co-op decided that subscribers whose address was in Montana would have a different area code and exchange than those in North Dakota.

On December 15, 1971, eighty-five residents gathered at the Squaw Gap Hall to be on hand for the first official phone calls placed from Squaw Gap. (See Document 3.) One of the calls went to U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz whose department administered the federal rural telephone program. The other went to North Dakota Representative to Congress Art Link. NBC news, the Wall Street Journal, radio stations, and local newspapers carried news of the celebration. One subscriber said “this is instant luxury . . . It’s like joining the world.” (See Image 6.)

Wall Street Journal reporter David P. Garino opened his slightly mocking article with a light-hearted joke:

"Some good news and some bad news:

The good news: For the first time ever, you can now pick up the phone and place a call to someone in Squaw Gap, N. D.

The bad news: There’s probably no one in Squaw Gap, N. D., you want to call."

Governor Bill Guy quickly responded to the article with a letter:

“Regarding your page-one article on telephone service reaching Squaw Gap: I have some good news for you and some bad news. The good news is that the people of Squaw Gap know a great deal about Wall Street and the confines of New York City. The bad news is that your staff reporter has conned you into thinking he knows quite a bit about Squaw Gap, N.D.”

Governor Guy went on to explain and praise the virtues of Squaw Gap:

“It would sound as though Squaw Gap has very little. And it is true that in comparison to New York and Wall Street, Squaw Gap does have very little. As a matter of fact, in many respects it has nothing. It has no crime, no air pollution, no water pollution, no noise pollution, no racial tension, no civil disturbance, no congested highways, no congested airways, and you can get from Squaw Gap to the next town quicker than most people can get from suburban New York to downtown Manhattan.”

Another letter challenged the Wall Street Journal’s article on Squaw Gap. This one was signed by the “Squaw Gap Chamber of Commerce.” The letter was written in a purposefully humorous way intended to ridicule the New York reporter’s view of Squaw Gap. The letter opened

“I got a little gravel in my craw and I ain’t gonna get no peace til I spit it out. I really-ize you got a sack full a chores tryin to handle your job as stuff reporter for the wall street paper and all, but that ain’t no excuse for tellin the wrong stuff.”

The writer went on to mock phone “congestion” in New York City that prevented his phone call to the Wall Street Journal from being connected. The writer ended the letter stating:

“I just want to say . . . we had to wait a spell to get our phones, but they work!!! And if anybody want to call us . . . they can. . . call us up . . . lines always open on this end.”

As Governor Guy pointed out, this community had treasures that New Yorkers could not imagine, much less appreciate. And yet, the residents of Squaw Gap welcomed more contact with New Yorkers. Perhaps the greatest quality of North Dakotans is that the “lines [are] always open.” (See Document 4)

Why is this important? The Wall Street Journal’s (WSJ) story of Squaw Gap’s new telephone line highlights some of the differences between North Dakota and more urban states such as New York. Distances between rural homes slowed the realization of telephone service in rural areas. What the Wall Street Journal reporter did not understand, however, was that distance was not an obstacle to community ties, the business of ranching or farming, or to technological growth. The people of Squaw Gap knew that they just had to work out a solution that would satisfy both the residents and the Reservation Telephone Co-op.

Telephone Works

The first type of telephone in common use was the magneto set. North Dakota farm families could purchase a magneto set by 1900. It was a wooden box that hung on the wall in most houses. (See Image 7.) The box contained a transmitter and receiver, two dry cell batteries, and a generator. Batteries powered the transmission. The generator was energized by the hand crank. A couple of turns on the crank made the phones ring along the line. A code determined how many rings sounded. One house might be two short rings and one long ring, or two long rings, or some other combination. The residents of each house knew their own ring.

One of the problems with the magneto set was that everyone else knew the rings, too. When they heard the phone ring, many neighbors on the line listened to someone else’s conversation. When extra people were listening on the phones, the power in the transmission was weakened. When lots of people were on the line, the speaker would have to shout to be heard. For this reason, the magneto set was often called the “crank and holler” phone. People who listened in on other people’s conversations usually kept quiet, but no one could count on a private phone conversation.

Early telephone lines were usually built by groups of farmers who connected the subscribers in their neighborhoods. Many of these phone lines were not connected to a wider system. The farmers pooled their labor and equipment to build the lines. Major merchandise companies such as Montgomery Ward sold instruction booklets on how to construct lines and install telephones. It was no accident that Montgomery Ward also sold telephones.

Telephone batteries were necessary until rural homes were electrified which did not happen in North Dakota until the late 1940s and early 1950s. However, as batteries improved, it became possible to run calls through switchboards and central exchanges. Switchboard calls had better sound. Better quality encouraged more people to subscribe.

Small telephone companies multiplied in North Dakota until 1950 when there were about 800 of them. Many of these small exchanges did not collect enough in service fees from the subscribers to have full-time maintenance. If there was a problem that the farmers could not fix, it remained a problem. Over time, insulation on the wires cracked; poles fell down in wind or snow storms. Many subscribers quit the line when quality of transmission and service declined. During the Great Depression, money was so scarce that many subscribers could not pay the phone bill, even though the cost of service was about $2 per month.

As the small farmer lines lost money, farmers used their ingenuity to keep the lines going. They used Mason jars for insulators; barbed wire substituted for a gap in the wire. In some locations, the lines were literally strung from fence post to fence post.

By the time the rural telephone loan program was added to the Rural Electrification Administration’s responsibilities in 1949, rural telephone service in rural North Dakota was a shambles. While service and telephone technology had continuously improved for urban subscribers, farm families were lucky to have access to a telephone at the nearest store. Those who had service at home were using the same magneto sets they had acquired when the line was first strung. There was no relief for the complex problem of supplying telephone service to rural North Dakota until 1950. Even then, it took three years to make the phones start ringing.

Why is this important? Probably no other modern technology meant more to farm families than a telephone. The phone connected farm residents with neighbors and family. A telephone call could rouse the help of neighbors in case of a medical emergency or a fire. Though rural families had a taste of the good things a telephone could bring to their homes and communities, the reality of regular, reliable telephone service remained out of reach for more than 50 years after telephones had become common in urban homes.

Document 4: Telephone Jokes

While Governor Guy had fun with New York newspapers over the telephones at Squaw Gap, it is good to remember that telephones have always fostered social relationships. One of the ways to understand how changing telephone technology has changed social relationships over time, is to read, or listen to, jokes. To understand these jokes, you need to know a few details:

• telephones were used to play practical jokes

• telephones presented a new way of making jokes about married couples

• before cell phones, people often used pay phones located in gas stations, stores, and on the side of a highway to make calls.

• long distance was a special call. The caller had to pay a fee by the minute, so a long distance call was announced in order to minimize the time spent on the phone

• in the 1980s, people purchased answering machines that recorded calls on magnetic tape. The answering machine was a new way to screen out nuisance calls.

The jokes below are presented in order of technological development.

- - - -

Soon after telephones became available in rural South Dakota, a telephone salesman tried to sell a telephone to a farmer. The farmer’s wife and children really wanted him to buy the phone, but he did not understand how it worked. He said, “It’s a fake! I’ve looked at that wire and there is no hole through it. How can you talk through that wire?”

One day the farmer and his family went to visit another family that had a telephone. They all decided that the farmer’s wife would go to another home where there was also a telephone. She would call the farmer so that he could see how nice it would be to have a telephone. As the farmer’s wife made the call, a storm came up. When the farmer answered the phone at the other house, lightning struck and sparks flew out of the telephone. “I believe it, now,” he said. “That was Mildred, all right!”

- - - -

A group of young boys decided to play a joke with the new telephone in the home of one of the boys. They called the drug store in their town. The druggist answered the phone: “Hello?” One of the boys asked, “Have you got Prince Albert in a can?” The druggist replies (after checking his tobacco shelf), “Yes.” The boy responds, “Don’t you think you should let him out?”

- - - -

The phone in Bjornson’s Minnesota farmhouse rang one evening. When he answered, the operator said, “This is long distance from Chicago.” Bjornson replied, “I knowed it’s a long distance from Chicago! How come you called to tell me that?”

- - - -

A truck driver named Bill Jones often stopped to call home from a pay phone at a truck stop in rural Montana. When the phone broke down, he was disappointed. It was the most convenient place to call home on his usual route. One day, he contacted the telephone company to report the pay phone out of order and asked to have it repaired. The operator agreed to get the message to the repairmen, but no one ever got around to actually fixing the phone.

Then Bill got an idea. He called the telephone company and told them that the phone was working now and there was no need to send a repairman. That is, the phone was working fine except that the quarter that he put into the phone to make the call was returned as soon as he hung up. The repair was made the next day. (See Image 24)

- - - -

A clever couple in Fargo placed this message on their answering machine: “Hello, you are talking to a machine. I am capable of receiving messages. My owners do not need extended warranty on their car, new windows, nor a hot tub, and their carpets are clean. They give to charity through their office and do not need their picture taken. If you're still with me, leave your name and number and they may get back to you.”