When a government agency takes possession of privately owned property, it is called a taking. This process can be done legally through a process called eminent domain, or the government can purchase the property at a price agreed upon.

When the Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation needed to acquire land for the dam and the irrigation canals, agents approached each private land owner and made an offer to purchase the land. (See Image 9.) Agents also approached the Indian tribes along the Missouri River. The tribes, rather than individual tribal members, made the agreement concerning reservation lands.

Many non-Indian landowners believed that the dam and the irrigation canals would be good for North Dakota. They willingly talked to the agents, and some came to agreement on a price for their lands. Others believed the purchase price was far too low. (See Document 1.) Many non-Indians went to court to have the purchase price adjusted. Those who refused to sell were told that the land would be taken anyway by eminent domain. (See Image 10.)

Tribes had fewer options. At first, they relied on treaty rights to defend their tribal lands against a taking. Then they turned to the government’s obligation to protect the trust lands of the reservations. The federal government contradicted its own policies concerning its relationship with Indian tribes, but did not help the tribes avoid the taking. Instead, the tribes were paid for their lands, and some substitute lands were offered in exchange. (See Document 2.)

Document 2. Talking about the Pick-Sloan Project

Garrison Dam and the Garrison Diversion generated a lot of discussion and controversy. Many of the early supporters of the Pick-Sloan project lost enthusiasm as costs rose and people complained about having their land taken from them. Some people recorded their experiences. Others today still remember what it was like to lose good farm land, ancestral homes, and the many resources they had come to depend upon.

“The year 1947 finds the Federal Government tackling a job of river control in the Missouri Valley. It is a program which will write a new chapter in the history of what is perhaps the wildest river in America. It is one which will turn a destructive stream into a constructive force for the benefit of millions of people who live in the valley and in the nation as a whole.” – General Lewis Pick, 1947

“In the days before the dam, every Indian family had livestock and property. They had grain crops and gardens. Because we were able to grow grain along the fertile river bottom, we were self-sufficient. We could use our grain to feed chickens, pigs, and livestock. The community spirit was something we lived every day. It showed in our community gardens. Our life was healthy. We had a hospital that had a permanent doctor.” - Cora Baker, Three Affiliated Tribes, quoted in “Goodbird, He Trusted the White Man” by Bob Elhert Sunday Magazine, Minneapolis Star and Tribune 21 June 1987.

“The fasting areas, the sacred places are all under water.” Donald Goodbird, Three Affiliated Tribes, quoted in “Goodbird, He Trusted the White Man” by Bob Elhert Sunday Magazine, Minneapolis Star and Tribune 21 June 1987.

“We are here asking you to cooperate with the Army engineers and your official Indian Affairs office in carrying out the law as now written. . . . I want to show you where we will place you people.” –General Lewis Pick, Army Corps of Engineers, quoted in Dammed Indians Revisited by Michael L. Lawson, p. 54.

“We are here today to remind you that we were on this land long before the first white man came and we are going to remain here forever.” – James Driver, Three Affiliated Tribes elder, quoted in Dammed Indians Revisited by Michael L. Lawson, p. 54.

“To relocate us on land comparable to that which we now hold,” the Indians claim,” will mean that the white people already owning that land will have to be evicted. This is a headache which has not yet penetrated the heads of some congressmen.” Unidentified Three Affiliated Tribes speaker, concerning location issues, 1946.

“[Away from the river, even] the jackrabbit packs a box lunch.” W. L. Gipp, Standing Rock Reservation Negotiating committee, 1951, quoted in Lawson, p.102.

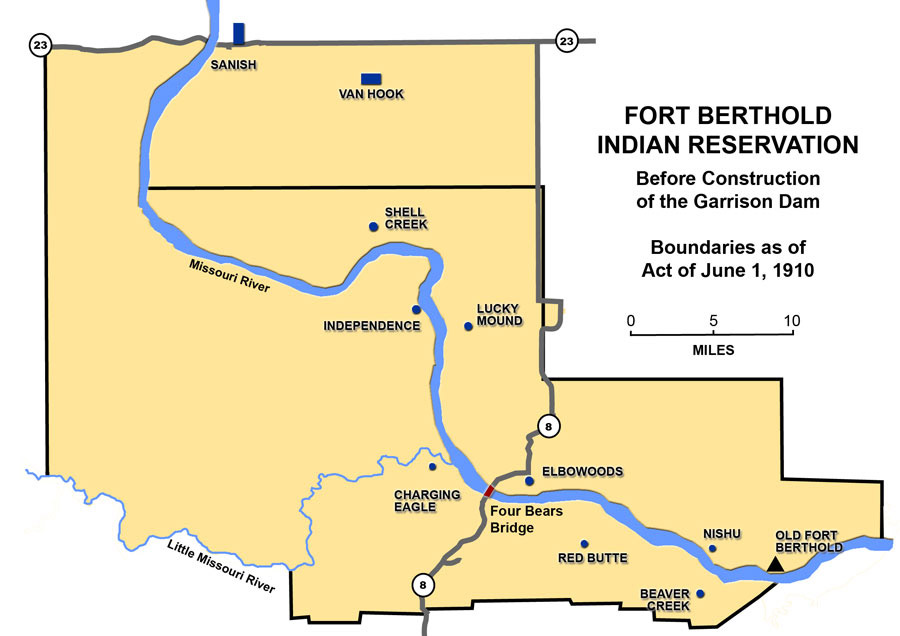

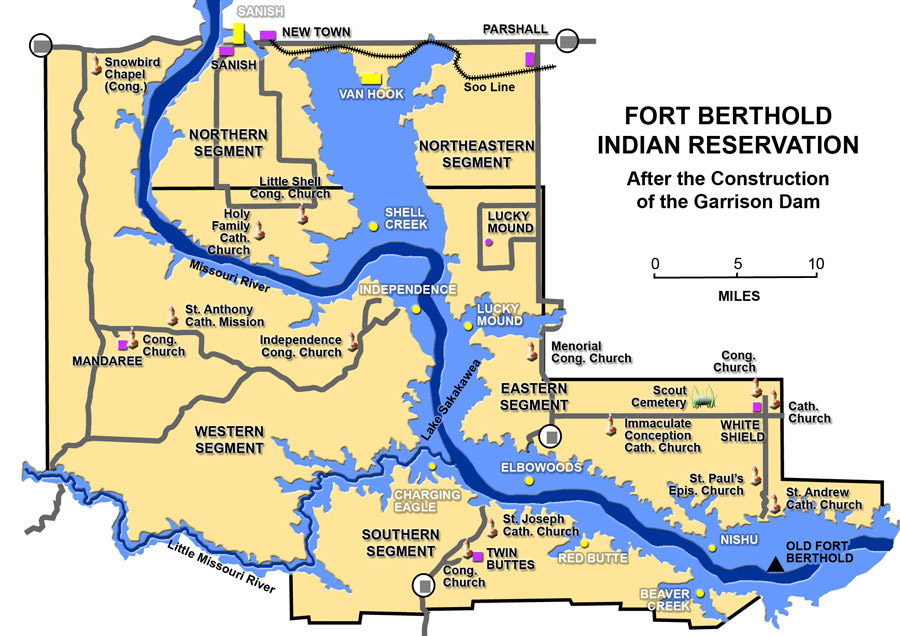

The Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold (TAT) were offered $5,105,625 for 156,000 acres. The money paid for the land that would be flooded was also supposed to cover the costs of relocating and re-building their towns. (See Map 1 and Map 2.) The tribes hired an appraiser who said the tribes should be paid $22 million. The tribe asked Congress to adjust the payment. (See Image 11.) In 1949, Congress agreed to pay TAT $7.5 million more. They were still $9 million short of the appraised cost of land and relocation.

In addition to loss of their lands, the Three Affiliated Tribes were also denied the right to use the lake shoreline for hunting, fishing, and grazing (the shore belonged to the Corps of Engineers). (See Image 12.) The tribes also lost rights to subsurface minerals within the reservoir area, and they were not allowed to cut timber from their land before moving “on top.” After 40 years of effort, the tribes finally won compensation from Congress in 1992. The Three Affiliated Tribes received $142 million. The interest from the fund paid for education, social welfare needs, and economic development on the Fort Berthold Reservation.

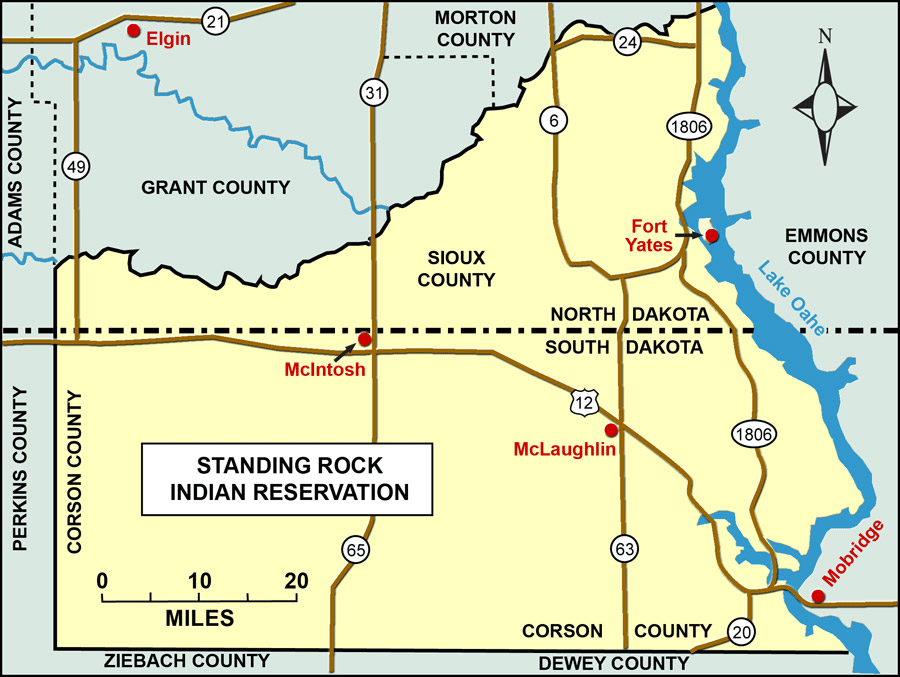

The Standing Rock Sioux tribe faced a similar situation in 1948 when the Army Corps of Engineers prepared to build Oahe dam north of Pierre, South Dakota. (See Map 3.) The Sioux tribe paid close attention to the efforts of the Three Affiliated Tribes to stop the dam and then to get adequate compensation. Their efforts to stop the Corps from building the dam were fruitless. (See Image 13.) The dam eventually claimed more Indian reservation land than any other dam in the United States. Though the project took about six per cent of the Standing Rock Reservation, it dislocated more than one-third of the tribal members on the reservation. Many lived near the river. Like the Arikara, Hidatsa, and Mandan, the Sioux would be moved “on top” into dry lands with little timber and protection from winter weather. For the loss of their lands, including much of the town of Fort Yates, the Sioux tribe received $1,320,000.

Why is this important? The loss of land in a state where land has been the single most important economic factor for thousands of years affected both American Indians and non-Indians. Farmers, ranchers, and Indians had deep ties to the land which dollars could not replace. Indian reservations did not received many of the benefits of the dam including good water systems on the reservations. The development of irrigation systems and access to electricity would come many years after the taking. As the cultural losses became evident, many North Dakotans began to question whether the advantages that came with damming the Missouri were worth the cost.