In 1918, newly organized Sioux County held an election to determine the county seat. Several towns were listed on the ballot, but Fort Yates received the most votes. The election determined that Fort Yates would be the county seat.

County seat is an important designation for a small town. It means that people will have to travel to this town to do business with the county such as pay taxes, serve on a jury, or make an appeal to the county commission. All businesses in town will benefit from that activity. So, when Fort Yates was chosen to be the county seat, it is not surprising that people in other towns worried about their future.

After the 1918 election, the Sioux County town of Selfridge decided to contest the election. A cattle rancher from Selfridge, Martin Swift, filed a lawsuit against the county commission (identified in the court case as Commissioner J. C. Leach) over the election. Swift claimed that 273 Indians had voted, but did not have the rights of citizens, including the right to vote. The number of Indians voting in the election ensured that Fort Yates would become the county seat.

District Judge Crawford heard the case. Crawford recognized the importance of this case. It was not just about the location of the county seat; the outcome of the case would have a major impact on the rights of American Indians in the future.

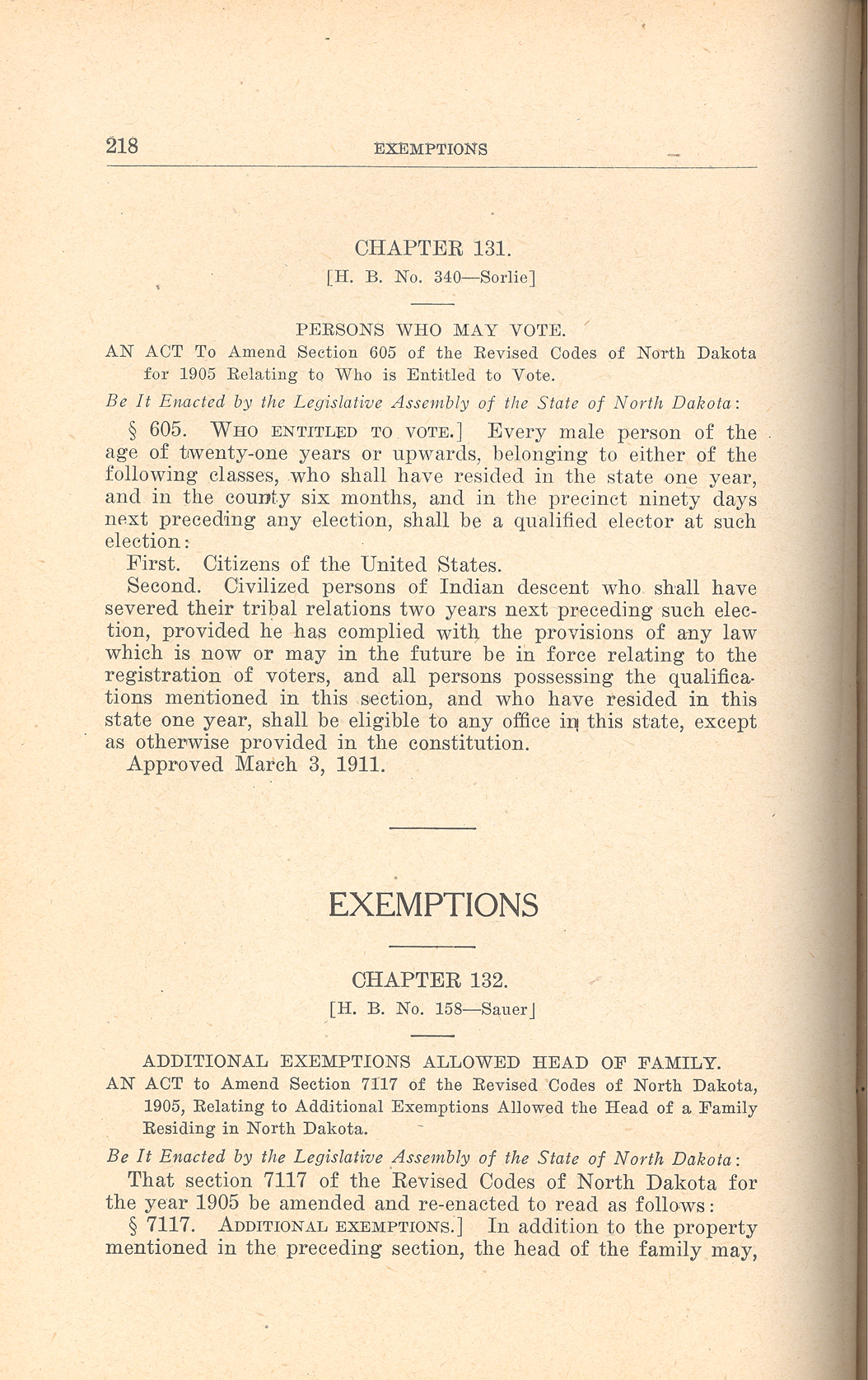

There were two basic questions for the court to decide. One was whether North Dakota laws concerning the qualifications for voting were properly applied in this election. The other question was whether the residents of Standing Rock reservation met state qualifications as voters.The early territorial voting laws limited the vote to “white men.” However, recognizing the important service and community leadership of several men of mixed Indian and European heritage, the territory passed special laws granting citizenship in Dakota Territory to 12 men. These were the sons of European American or French Canadian fur traders and Native American women. Though they were born in the United States, their Native American and/or Canadian parentage raised questions about their citizenship. Under state law, voters included “civilized persons of Indian descent who shall have severed their tribal relations two years next preceding such election.”

Witnesses testified to the “civilized” qualities of the Standing Rock tribal members. One witness stated that the Standing Rock Lakotas did not recognize chiefs and “had the habits and customs of white men.” Witnesses stated that most Indians under the age of 40 could read and write, and many attended church. No one questioned the loyalty of Standing Rock residents to the United States since many young men had served in the armed forces during World War I and some gave their lives for their country (See Unit III.Lesson 4.Topic 11.Section 4).

When this case first came to court in late fall 1918, World War I had just come to an end, the severe influenza epidemic had taken a toll on the county, and tribal lands were being sold (Unit III.Lesson 1.Topic 4. Sections 7 and 9). There were many charges of fraud and illegal voting in the county seat election, but the only charge that came to court was the question about the right of Indians to vote.

The case finally went to the North Dakota Supreme Court. On May 26, 1920, the court issued the opinion in Swift v. Leach that Indians of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe were qualified voters under North Dakota law. The court decision read:

Trust-patent Indians [who, under the Dawes Act, owned land in their own name] have in fact become civilized persons of Indian descent and, in fact, for more than two years preceding a general election have actually severed their tribal relations and have adopted the modes and habits of civilized life, and where it appears under the testimony of the Superintendents of the Indian Agency in charge of such Indians, both present and former and others, that they were qualified as civilized persons, to be electors . . .

Swift v. Leach is one of the earliest decisions about the citizenship status of American Indians in United States law.

After the 1918 election, the Sioux County town of Selfridge decided to contest the election. A cattle rancher from Selfridge, Martin Swift, filed a lawsuit against the county commission (identified in the court case as Commissioner J. C. Leach) over the election. Swift claimed that 273 Indians had voted, but did not have the rights of citizens, including the right to vote. The number of Indians voting in the election ensured that Fort Yates would become the county seat.

Why is this important? Martin Swift raised the legal issue of the right of Indians to vote at a time when voting rights were expanding. Though Asian Americans could not vote and African Americans met stiff resistance when they tried to vote, American women had been gaining access to voting rights. Over the next four decades, voting rights continued to expand.

The case of Swift v. Leach brought the matter of Indian citizenship and suffrage to the public. As the states expanded the guarantees of citizenship, the nation had to follow suit.

Voting rights was the final step in gaining full citizenship. North Dakota and the nation could no longer treat American Indians as inferior and unqualified for full citizenship rights and obligations.