The North Dakota National Guard was called to federal duty in July, 1917. There were 4,195 guardsmen in federal service. In addition, 19,772 North Dakota men volunteered for service in the Army, Navy, or Marine Corps. The selective service (sometimes called the draft) enrolled another 11,481 men.

,-ca-1917-optimized.jpg)

Many men who were drafted applied for and received exemptions or deferments. The deferments were usually because there were people dependent on them or because they had to work on the home farm. Farm exemptions were considered very important. Crops had to be raised to feed both soldiers and civilians.

College students trained for war on their campuses. The Student Army Training Corps allowed young men to train for military service while completing their college courses.

Medical doctors were particularly important to the war effort. As soon as war was declared, a Bismarck doctor, Eric P. Quain, organized a Red Cross hospital unit and set it up in France. He staffed the hospital with volunteer doctors and nurses from Bismarck. Due to his efforts and his skills, Dr. Quain was made chief of surgical services in military hospitals in France. (See Image 1) During the war, 148 nurses and 200 doctors from North Dakota served with the Army Medical Corps. Other medical personnel served with the Red Cross.

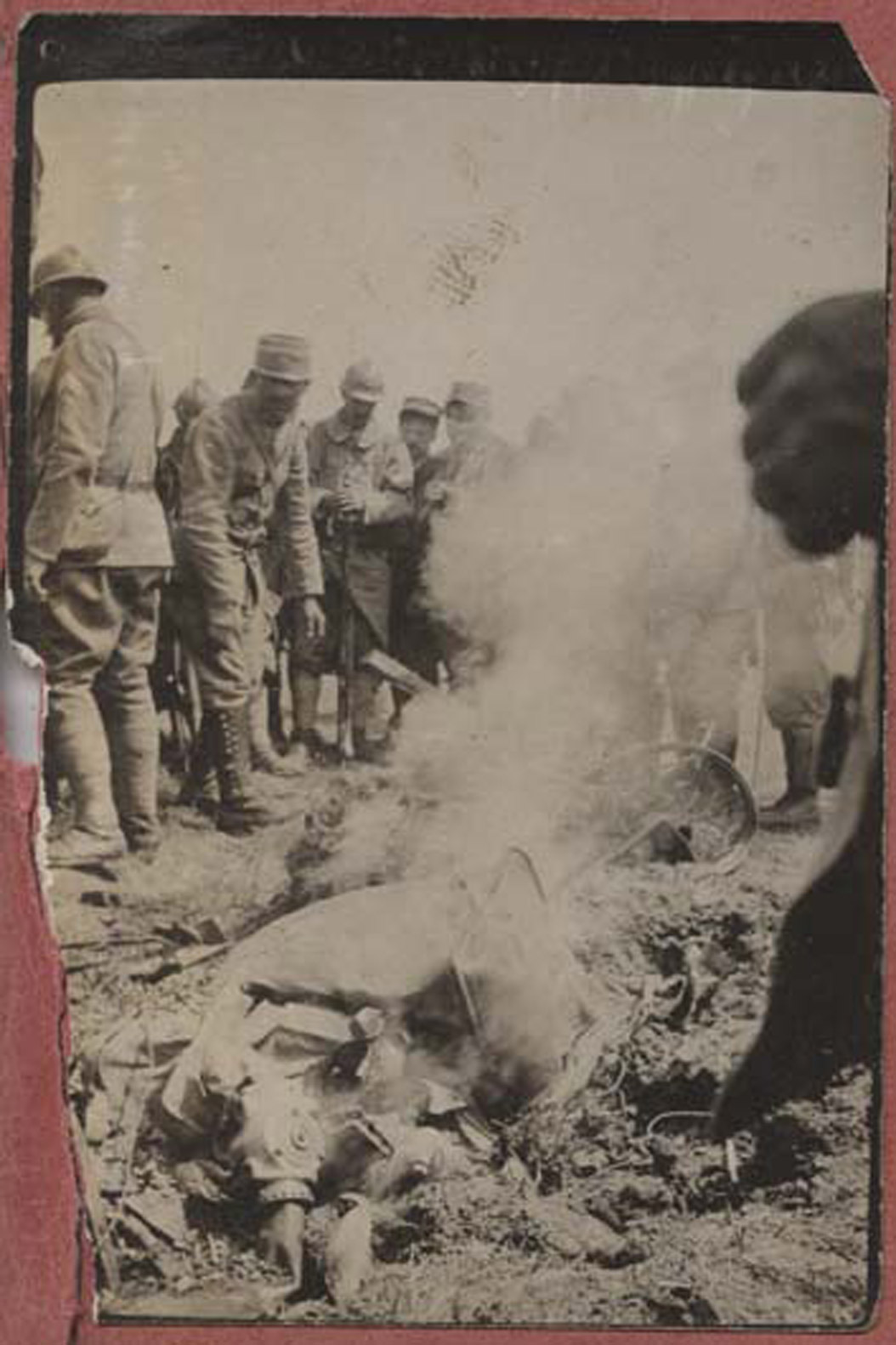

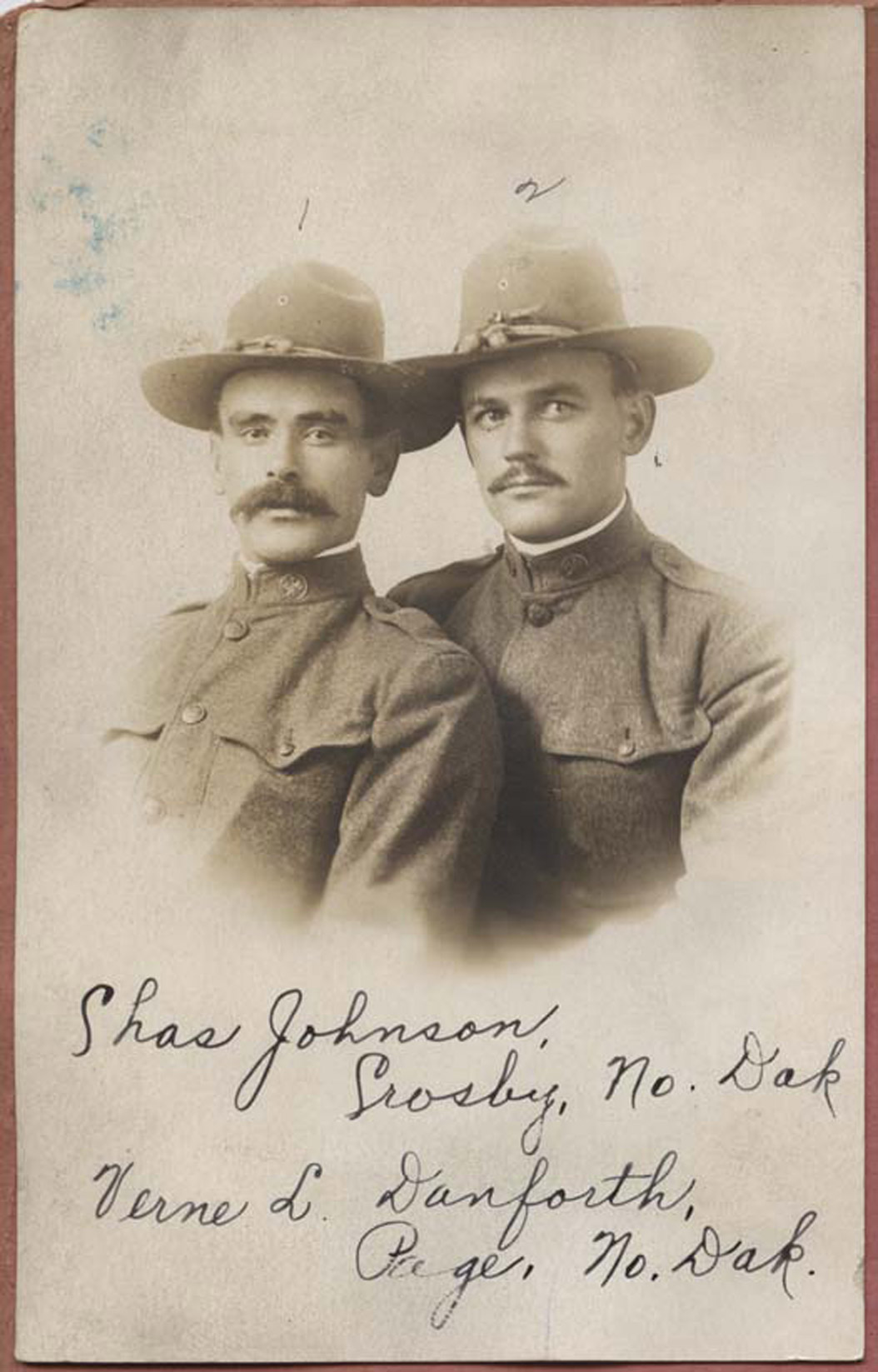

The war dragged on for more than four years and devastated the European countryside. (See Image 2) The mortality of English, French, and German soldiers was astounding. More than 37 million soldiers and civilians died during the four years of warfare. (See Image 3) This war saw the introduction of new weapons including tanks, (See Image 4) airplanes, flame-throwers, and poison gas. (See Image 5) More than 1,300 North Dakota men died in the war. Of these, 663 died of combat wounds. Six hundred forty-two soldiers died of disease.

When war ended on November 11, 1918, the world rejoiced. The Allies had won the war. The soldiers slowly returned home, but some were unable to carry on life as they had lived before the war. A medical problem that was called “shell-shock” in 1919 (today this is known as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD) affected many of these soldiers for the rest of their lives. In addition, some soldiers been attacked by “mustard gas,” an airborne weapon used by the Germans that destroyed lung tissue. These young men were permanently disabled. However, some soldiers gained experience that allowed them to move into important and interesting careers when they returned home.

The North Dakota legislature, still strongly influenced by the Nonpartisan League, was the first state to give its veterans a bonus. Each man who had served in the Armed Forces received a bonus of $25 ($377 in current value) for each month of service. The legislature also dismissed the debts of the former soldiers. By 1928, the state had paid veterans more than $8,800,000 (nearly $132,700,000 today.) No other state did as much for its veterans.

Why is this important? It is important to understand that North Dakota served its country well during World War I. Many North Dakotans had opposed the war, but once the United States declared war on Germany, young men and women enlisted in the effort to serve the country. North Dakotans made extraordinary contributions to the war effort which was deeply appreciated by the people of the state and the nation.

A Soldier's Experience

Joseph Walter Plunkett was born on Christmas Day, 1892 in Sheldon, North Dakota. We know very little about his father, John, who was not present in the family by 1900. Walter’s mother Eva, (See Image 6) supported her family of three children by working as a nurse and by taking in boarders.

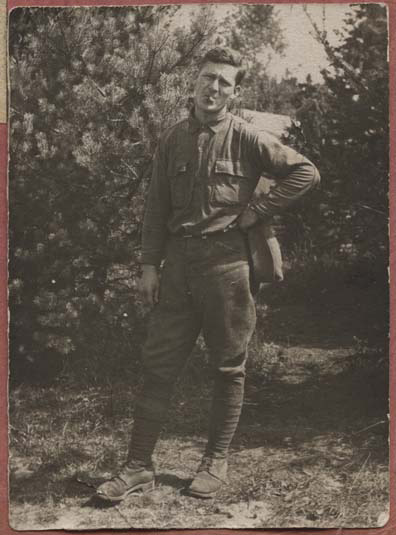

Walter grew up in Jamestown with his younger sister, Eva, and an older brother. By 1915, Walter worked for a Jamestown mechanic’s garage as a chauffeur. He enlisted in the Army in August, 1917.

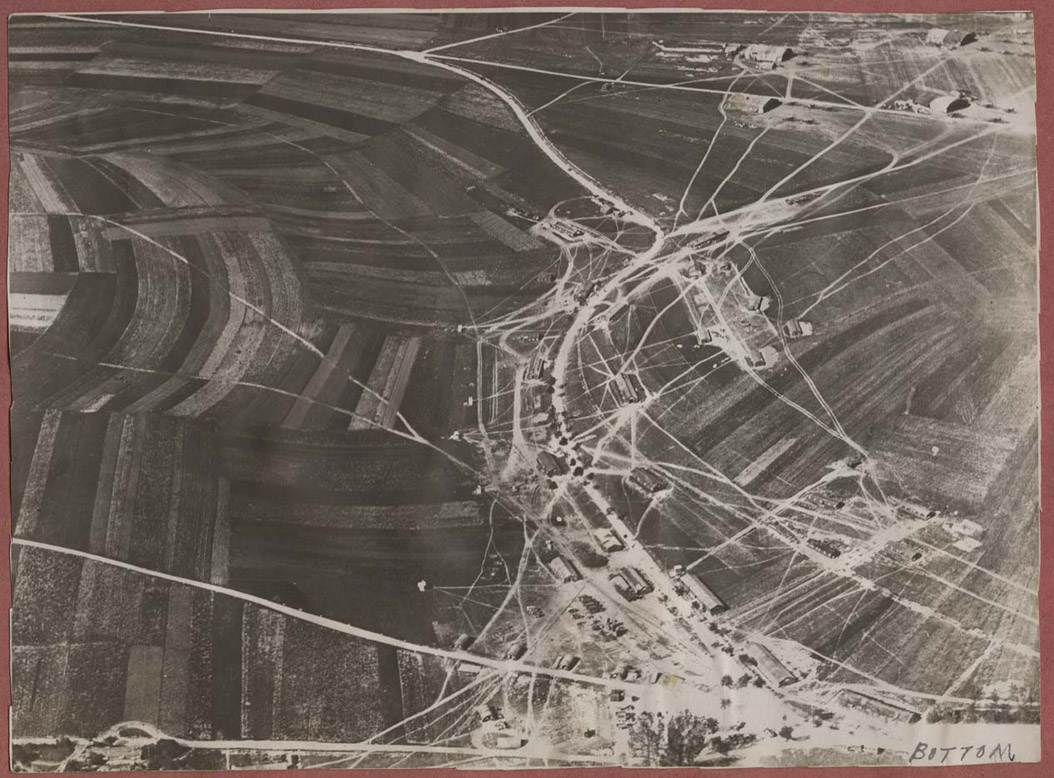

Walter was sent to Europe attached to the Army’s 116th Aero Squadron. (See Image 7) Walter’s military position was chauffeur. He traveled about picking up vehicles and transporting people to different places. In his position, he was able to meet many interesting people. He was in Paris several times.

Walter wrote many letters from Europe to his mother and sister. Because he was not in combat, he always assured his mother that he was safe and doing well. While in Europe he encountered many friends from Barnes County and others from North Dakota. Among them was the young nurse from the Jamestown area named Orma. Walter, or “Punk” as he was known, visited with Orma often. (See Image 8) Walter was heart-broken by her sudden death which may have been caused by Spanish influenza.

One of Walter’s letters to Eva (dated Thanksgiving, 1918) told about the souvenirs he was sending home. Many soldiers collected souvenirs taken from German (or “Boche”) soldiers. Soldiers also purchased trinkets in France to send home. The letter had to be checked by censors to be sure that Walter did not reveal any military secrets. Plunkett also brought home many photographs. He probably took some of these pictures himself. Others appear to be photos he purchased.

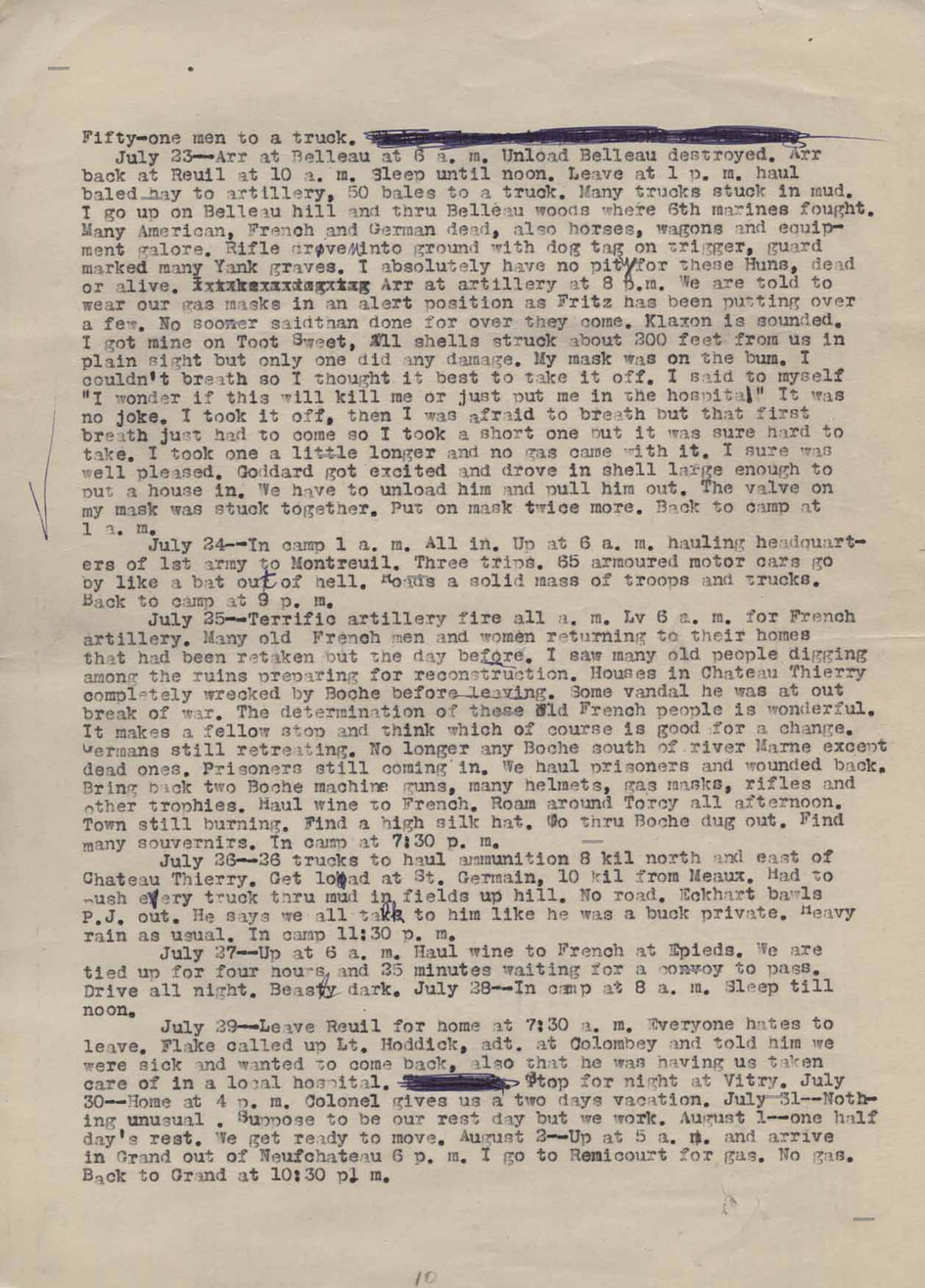

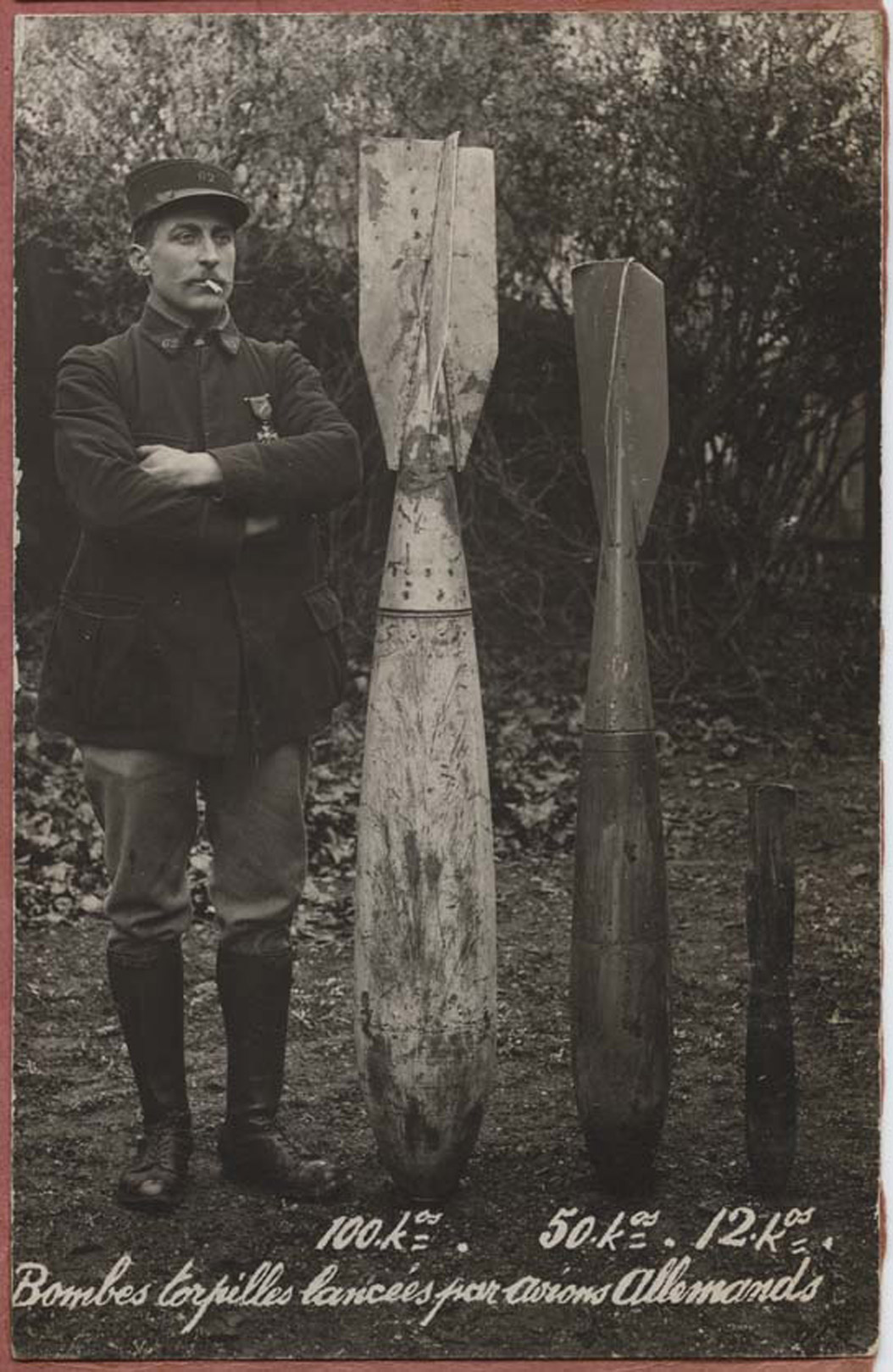

Walter Plunkett’s papers also include a typewritten copy of his diary of his overseas service. Plunkett’s diary indicates that he worked with an air squadron. The use of planes to deliver weapons was new for both the U. S. Army and the German army. (See Image 9) Aerial bombing was a far more effective means of destruction than shelling a city with guns from the land. However, not all of the bombs exploded which explains the photographs that Plunkett collected showing the unexploded bombs that landed on Nancy, France in 1916. (See Image 10) Plunkett personally experienced German bomb raids ("Fritz visits us. Drops 38 pills") and recorded the death and destruction of the war.

Plunkett had a little trouble with Army discipline. Though he was mustered out of service with an honorable discharge, he was criticized by superiors from time to time for not showing proper military respect. His statement on February 4, that he “was a human being” suggests that he took both his mechanical skills and his American pride to war with him.

Plunkett returned home from France in May, 1919 after spending 18 months in Europe. He returned to his old job as a chauffeur for a mechanic’s garage in Jamestown.

Why is this important? Walter Plunkett’s service was typical. Though he was not a combat soldier, he did experience warfare. The support services he provided were critical to the success of the U.S. operations against Germany. The war broadened his world experience and he brought home memories and objects that he held onto all of his life. His letters, diaries, and photographs remind us of one of the bloodiest and deadliest wars the United States has ever fought.

Source: SHSND MSS 20945

Plunkett Collection Photo Essay

Walter Plunkett took photographs and purchased souvenir photographs while he was on military duty in France. These photographs explained his experience in the war to his family and friends back home. The images of the bombs that landed on Nancy, France and the pictures of the destruction of villages such as Richecourt increased American’s interest in the war. People who saw these images and read newspaper articles about the atrocities committed by German soldiers (“Boches”) came to view Germany as an evil enemy.

These photographs are a small part of the collection of dozens of images that “Punk” Plunkett sent home along with souvenirs and letters to his mother and sister. Walter Plunkett returned to civilian life in 1919. He died in 1981 at a Veteran’s Administration hospital in Battle Creek, Michigan.

North Dakota’s Nurses

When the United States entered the Great War in April, 1917, there were only 403 nurses on duty in the Army and Navy. The call went out to recruit nurses to be trained for military and civilian service by the American Red Cross. Two hundred seventy nine (279) nurses from North Dakota volunteered for service.

North Dakota nurses responded in higher numbers than did nurses from other states. More than 20 per cent of registered nurses enrolled with the Red Cross. More women signed up for training as nurses as the war progressed.

Nurses were not enlisted in the Army and were not commissioned as officers. They were assigned to the Army Nurse Corps. However, during the war and the influenza epidemic, the Red Cross served as the official source of nurses for the armed forces.

Many of the young women who signed up with the Red Cross wanted to serve overseas. Five young nurses from North Dakota went to England in the spring of 1917 to serve in hospitals under orders of the British Expeditionary Forces. Forty percent of North Dakota’s volunteers served overseas with the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF.) The rest of the nurses served in military hospitals and training camps in the States. The chance to go to France, perhaps to see Paris, drove many women to enroll. As Ingeborg Dalborten of Grand Forks said, “I had a love for the strange and unheard of adventures in seeing foreign countries.”

The requirements for a nurse volunteer were very high. She had to be of good moral quality and well educated. The Red Cross required that nurses be between 25 and 40 years old, unmarried, in good health, and be either a registered nurse or a graduate of a two-year nursing school. As the need for nurses rose to more than 20,000, some of those requirements had to be set aside.

When the nurses left North Dakota for training, their hometowns sent them off with farewell parties. In Bismarck, the nurses boarded a train for New York while a band played and Governor Frazier and a crowd waved from the platform and threw rice for good luck.

Once in training, the nurses had to wear heavy wool dress uniforms, capes with a scarlet lining, white service uniforms, and much-hated yellow shoes. They did not wear civilian clothes for the duration of the war. After enrolling, they had several weeks of training in military regulations and sanitation procedures. Most of the training took place in New York for those going overseas. The nurses left New York in small groups during the night so that their departure would not alert the enemy. (See Image 20)

In Europe, the nurses were generally assigned to mobile tent hospitals (near the front lines) or evacuation hospitals on Army bases. Though nurses were not allowed to work on the front lines, their hospitals were sometimes bombarded by enemy fire. (See Image 21) The number of sick and wounded easily overwhelmed the medical staffs at all overseas hospitals. North Dakota’s nurses performed well under fire, but few of them forgot the horrors of war.Mary Ray remembered how difficult it was to work under the conditions of war. “We worked on very little sleep until the drives [military campaigns] were over . . . we operated in tents, chateaus, and barracks. Always we were under continual barraging [bombardment.] During the Chateau Thierry drive, which was the heaviest, we had from 250 to 300 boys waiting to be operated on.”

Nurse Lillian Blackwell wrote home: “patients, patients-simply pouring in and lying all over the hillsides under the trees. They are so tired, many only slightly wounded, but how they sleep from sheer exhaustion! Over 1,100 were admitted to Evacuation VII last night; roads are lined with trucks. We had 8,100 in eight days for our 300 bed hospital, but 1,100 in one night.”

Jennie Mahoney had a similar experience: “We worked all night and the following day in a building with windows, doors, and shell holes covered with heavy dark blankets, lest the enemy see a glimmer of light from our candles, the noise of guns and exploding bombs striking terror in our hearts, our souls sick at the sight of our boys.” Quoted in Peterson and Jensen, p. 330.

Most of North Dakota’s nurses served at military bases or training camps in the United States. Though the service was not as exciting, the work was just as necessary. When Spanish influenza broke out among the soldiers, the nurses could barely keep up with their work. From mid-September to early November of 1918, more than 316,000 soldiers and sailors came down with the flu. Mary Lynch recalled that soldiers died at a rate of 200 to 300 per day during the second and third week of the epidemic at the training camp where she was stationed in Illinois. The duty was demanding and tiring. Mary Teichmann worked as the only night nurse in a ward of 192 patients.

When the nurses returned home, they were discharged from service in New York City. They had to find the money to travel home to North Dakota. Sometimes, the people of their hometown would raise the money to pay their way. The nurses spent some months recuperating from the demands of war service. Many then turned to the Red Cross to help them find new positions. About two-thirds of the nurses married and left their profession. While five Army nurses died from war wounds, none were from North Dakota. However, five North Dakota nurses died of the flu while in service.

Why is this important? North Dakota’s citizens responded vigorously to the demands of war. However, it is important to remember that women served as well as men. Women brought much needed skills to the Army and Navy.

Women’s war service helped to bring about approval for the Constitutional amendment (19th) to grant women voting privileges. Many women found new career opportunities with the nurse’s training they received during the war. The war work of nurses and other Red Cross volunteers generated greater respect for women and their work skills.

Source: Susan Peterson and Beveraly Jensen, "The Red Cross Call to Serve: The Western Response from North Dakota Nurses" Western Historical Quarterly, vol. XXI No. 3 (August 1990): 321-340