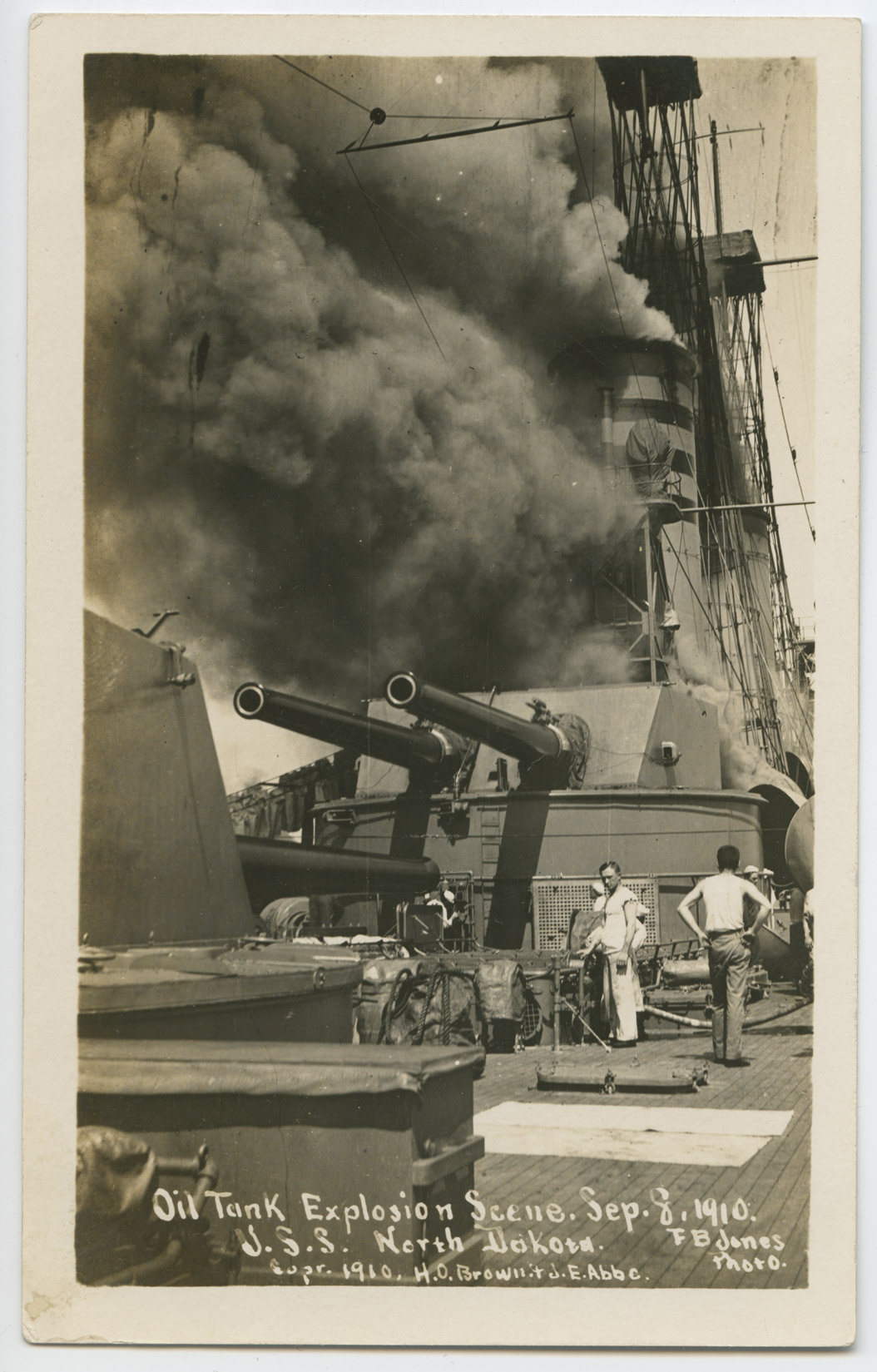

At no time was the community feeling aboard the North Dakota tested more seriously than on the occasion of the fire. On September 8, 1910, the North Dakota had been fit for sea duty for only a few months. She was returning with her relatively young and inexperienced crew to Hampton Roads, Virginia after fleet exercises and was running on fuel oil. A fire broke out around 10:30 a.m. in fuel oil storage room No. 3. Captain Gleaves ordered the ship to drop out of formation so as not to endanger the other ships of the division. Gleaves gave two orders: put out the fire, and retrieve the dead and injured from the engine room. (See Image 9)

While dense black smoke poured out of the ventilators and hatchways (doors to the lower levels of the ship), the fire was dampened by purposely flooding the engine room and the oil storage area with sea water. The hold of the ship filled with nine feet of water, but the fire continued to burn above that level.

Without the engines, the pumps could not be operated to put out the rest of the fire. The Commander in Chief of the Fleet, Admiral Schroeder, ordered a tugboat and the USS New Hampshire to stand by the North Dakota to give all aid possible. The tugboat pumped water onto the fires burning above the flooded engine room. For about one hour, the North Dakota was in grave danger of exploding because the powder magazine (gunpowder storeroom) was located just above the fire. Fortunately, the flames did not reach the gunpowder.

The newspapers reported that officers and sailors worked closely together. “Realizing this danger – they worked coolly and with great courage. Capt. Gleaves and every officer aboard fought flames shoulder to shoulder with the men, and when the danger had passed they were as grimy as [coal] stokers.”

Later in the day, the North Dakota was able to put four boilers back into service. With the little power they provided, the ship was able to raise the anchors and steam slowly into port.

In spite of the quick efforts to put out the flames, three men, Joseph Schmidt, Robert Gilmore, and Joseph Strait, died in the fire. All were enlisted men who held the job of coal passer. Ten men, including one officer, were injured and were moved to the hospital ship USS Solace for treatment before being transferred to a hospital in Virginia.

At the board of inquiry, Lieutenant Commander Orin G. Murfin, who sustained burns in the fire, testified that he was in the engine room and ordered the room abandoned when he saw a flash of flame run along the oil lines. But the fire quickly grew and filled the room with gasses and flames preventing three of the men from escaping the fire room.

Ten men were honored for heroic actions in the fire. Thomas Davis, John Quinlan, George Ellis, and Arnold J. Smith received warm commendations. Six men were awarded the Medal of Honor for “extraordinary heroism.” They were Thomas Stanton, Karl Westa, Patrick Reid, August Holz, Charles Roberts, and Harry Lipscomb. They also received a one-hundred dollar bonus. Davis, Quinlan, Ellis, and Smith closed off the engine fires in a fire room where the heat was so intense they had to be sprayed with fire hoses to avoid dying of the heat. Stanton, Westa, Reid, Holz, Roberts, and Lipscomb were honored for entering the burning engine room to put out the fire. They also removed the dead through waist-deep water in intense heat and dense smoke. Charles Roberts, a machinist’s mate, was overcome by smoke. Before World War II (1941–1945) it was possible to earn the Medal of Honor for bravery in non-combat situations which was the case for these six men.

The board of inquiry found that a leak in the oil pipes had led to the fire. The crew repaired the damage, and the ship rejoined the fleet by September 29. Following this fire, the Navy made efforts to protect the powder magazines from the heat and possible fires in the engine rooms.

Unfortunately, the North Dakota had another fire and one more death. After repairs to the damages from the September 8 fire, the ship sailed with the fleet to England and France. On December 14, 1910, an explosion in the coal bunkers burned a sailor identified only as Evans. Evans died of the burns shortly after.

The North Dakota continued to have trouble with the Curtis turbine engines. In February 1915, the engines were damaged while returning from Cuba. In June 1915, the North Dakota was ordered into a shipyard where the engines were to be repaired or replaced in a major overhaul to the satisfaction of the engineer officers who found these turbines to be unreliable.

Why is this important? Engine trouble turned out to be the North Dakota’s greatest failing. When she was running well, she could operate efficiently and at great speed. But when troubles came, they tested the strength, courage, and devotion to duty of all members of this ship’s community. Routine drills on managing the engines and fires helped the men work efficiently to save the ship and all the men aboard. The relationships the men built as friends, co-workers, and teammates helped them work together in a time of great danger. The officers earned the respect of the men with their efforts to put out the fire.

Source: New York Times, September 9, 1910