In 1862, war broke out between the Eastern Dakotas (the Santees) and the people who lived in southern Minnesota. The war lasted about six weeks and resulted in hundreds of deaths. Many settlers were taken captive.

Some Dakotas fled across the Red River into northern Dakota Territory. They headed for an area where they had previously camped and hunted near Devils Lake. The Army did not try to follow them in 1862. However, in 1863, Minnesota volunteer soldiers under General Henry H. Sibley crossed into Dakota Territory. Their trail took them across the Red River at Fort Abercrombie, northwest to Devils Lake, and west to the Missouri River. They searched for bands of Dakotas who had been involved in the war in Minnesota.

U.S. Army troops and Dakota Cavalry volunteers under the leadership of General Alfred Sully also entered northern Dakota Territory in the summer of 1863. Sully’s regiments traveled up the Missouri River from the southern part of the territory. Sully’s troops were to meet Sibley’s troops east of the Missouri River. Together, the combined regiments planned to surround the Dakotas. Both generals expected to meet the Dakotas in battle.

The Dakotas who had come to Dakota Territory from Minnesota (the people Sully and Sibley considered “hostiles”) had left the area or joined other bands. Sibley could not find Sully and returned to Minnesota after three brief battles with some bands of Dakotas who were hunting east of the Missouri River.

In late August, Sully received information that the Dakotas were hunting about 100 miles east of the Missouri River, in what is now Dickey County. Sully marched east and, on September 3, 1863, the soldiers found a hunting camp of several bands of Dakotas (mostly Western or Teton Dakotas) at a place called Whitestone Hill.

Some Army officers talked with some of the leaders from the camp, but they could not come to an understanding before the rest of the soldiers arrived. The soldiers attacked the camp killing 150 Dakotas and capturing 156 women, children, and a few men. Some Dakotas escaped. Sully spent the next few days rounding up wounded Dakotas and destroying the camp. The soldiers burned the tipis, household goods, weapons, and 400,000 pounds of drying buffalo meat. The captives were taken to Crow Creek reservation in southern Dakota Territory. There were few, if any, Dakotas from southern Minnesota at the hunting camp.

The following summer, Sully returned to northern Dakota Territory with more soldiers. He marched his troops up the Missouri River valley to a place just north of the Cannonball River. There, he paused long enough to establish Fort Rice and to plan a campaign against the Dakotas in the area.

In late July, 1864, Sully marched north with 2,200 soldiers. General Sully had received information that the Dakotas were camped in the Killdeer Mountains. On July 28, Sully’s troops attacked a large village of Dakotas on North Killdeer Mountain. Among the leaders in that camp was Sitting Bull. Sully’s battle plan and his artillery (called mountain howitzers,) gave the Army an advantage over the large village of Dakotas. The soldiers overran the village. Many Dakotas died in the battle, but most escaped into the badlands of the Little Missouri River. Two men in Sully’s command died in the Battle of Killdeer Mountain. Again, Sully’s troops destroyed all of the food and tipis of the village.

Sully tracked the Dakotas through the badlands in a grueling march through terrible heat and drought conditions. In addition, the soldiers were escorting a wagon train of Anglo-Americans headed to the gold fields in Montana. For several days, the Dakotas attacked the soldiers from the buttes. The soldiers finally reached the Missouri River where steamboats were waiting for them. They returned to Fort Rice without defeating the Dakotas.

Why is this important? The two generals found Dakota hunters and their families preparing for the coming winter. By destroying the Dakotas’ tipis, clothing, and food supply, the Army left the people in very bad condition for the coming winter. Sully wrongly claimed to have defeated the Dakotas soundly in both battles.

However, the Dakotas were angry that the soldiers had attacked and destroyed their goods without cause. The Western Dakotas had not participated in the U.S.-Dakota War in southern Minnesota. After the battles at Whitestone Hill and Killdeer Mountain, the Dakotas understood that the soldiers intended to do them harm and invade their treaty lands.

These battles may be among the most important battles between the Dakotas (also called the Sioux) and the Army. The battles led to more conflict and more distrust between the American government and the Dakotas. Many more battles followed before the Sioux defeated the Army at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876.

The battles of 1863 and 1864 took place during the Civil War and are recorded as Civil War battles. The battles in Dakota Territory drew men, ammunition, horses, and other supplies away from the war to preserve the Union.

Civil War Battles in North Dakota : Documents

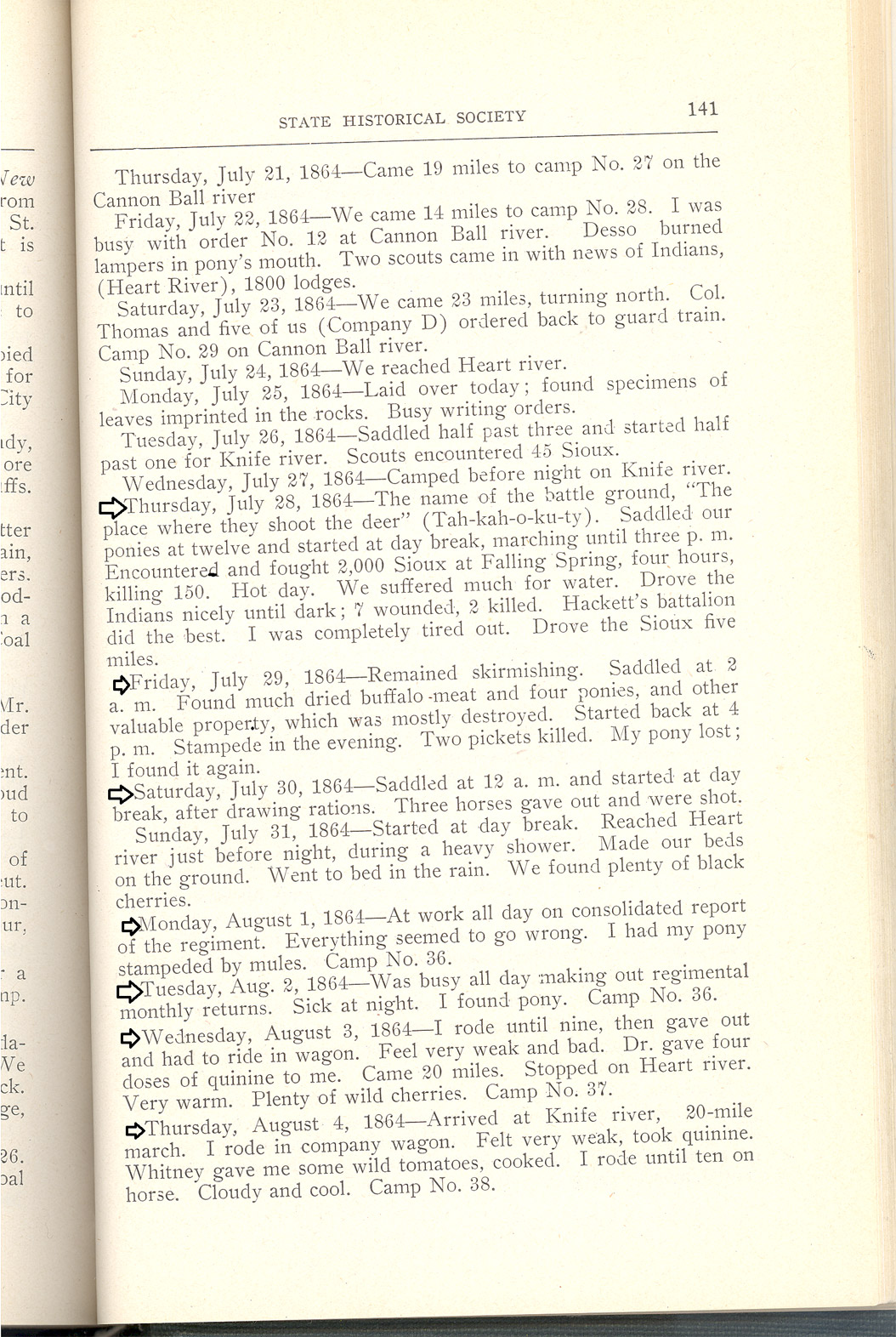

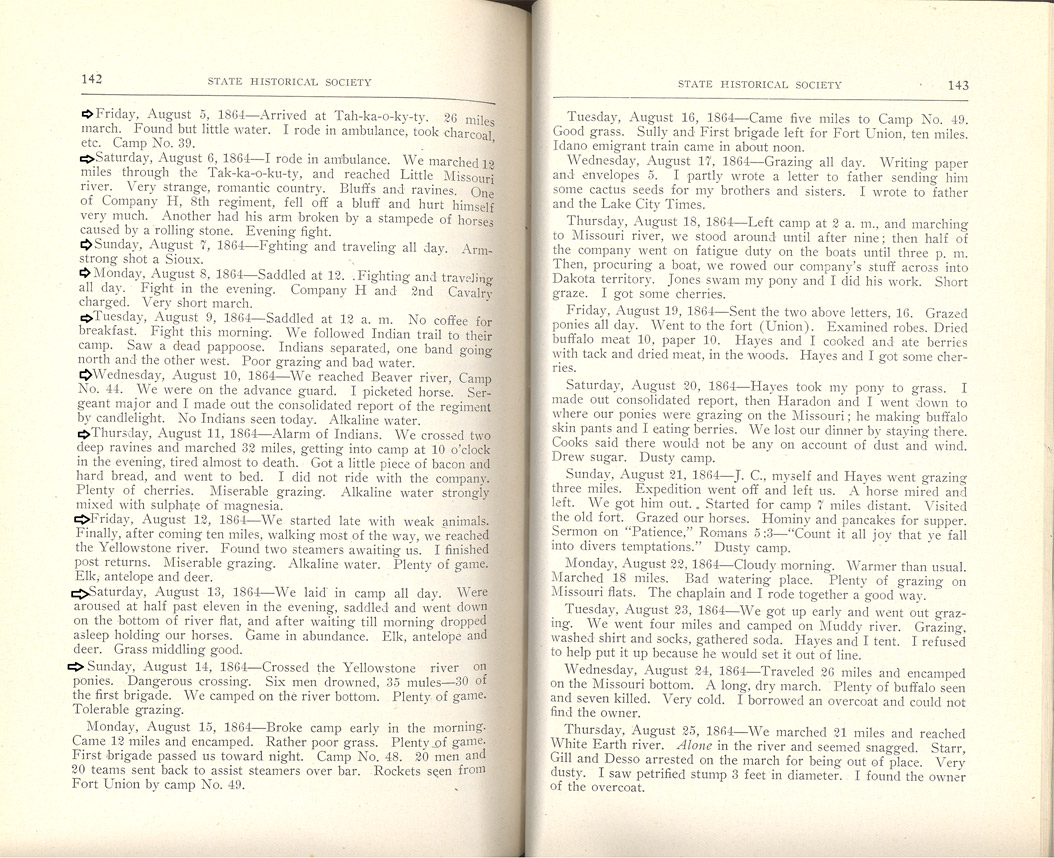

These two documents are excerpts from longer documents. Document 1 was written by Lewis C. Paxson who was born in Pennsylvania in 1836. In 1862, he moved to Minnesota where he taught school. He enlisted in Company G, 8th Minnesota Infantry in August 1862. He enlisted because war had broken out between the settlers of Minnesota and the Santee Dakotas who lived on a reservation in southern Minnesota. By November, 1862, Paxson’s company was stationed at Fort Abercrombie on the Red River. While serving with the 8th Minnesota Infantry, he participated in the Battle at Killdeer Mountain on July 28, 1864. Paxson continued to serve in the Army throughout the Civil War. He was promoted to First Lieutenant in June, 1865. He was mustered out of the Army in August 1865. He later moved to New Jersey where he operated a store and a dairy farm.

Paxson was probably a sergeant in 1864. We can read in his diary that he was responsible for keeping records and making reports. His diary tells us what he was thinking and feeling on the day of the Battle of Killdeer Mountain and the days of skirmishing that followed. He notes that he was pretty sick after the battle which may have been due to the excessive heat and lack of water during the battle. The entry for July 28 refers to “Hackett’s battalion” which is probably supposed to be Brackett’s Battalion. His estimate of 150 Indians killed is probably a little high. General Sully estimated that between 100 and 150 Dakotas died in the battle. The Dakotas claimed 31 died in the battle.

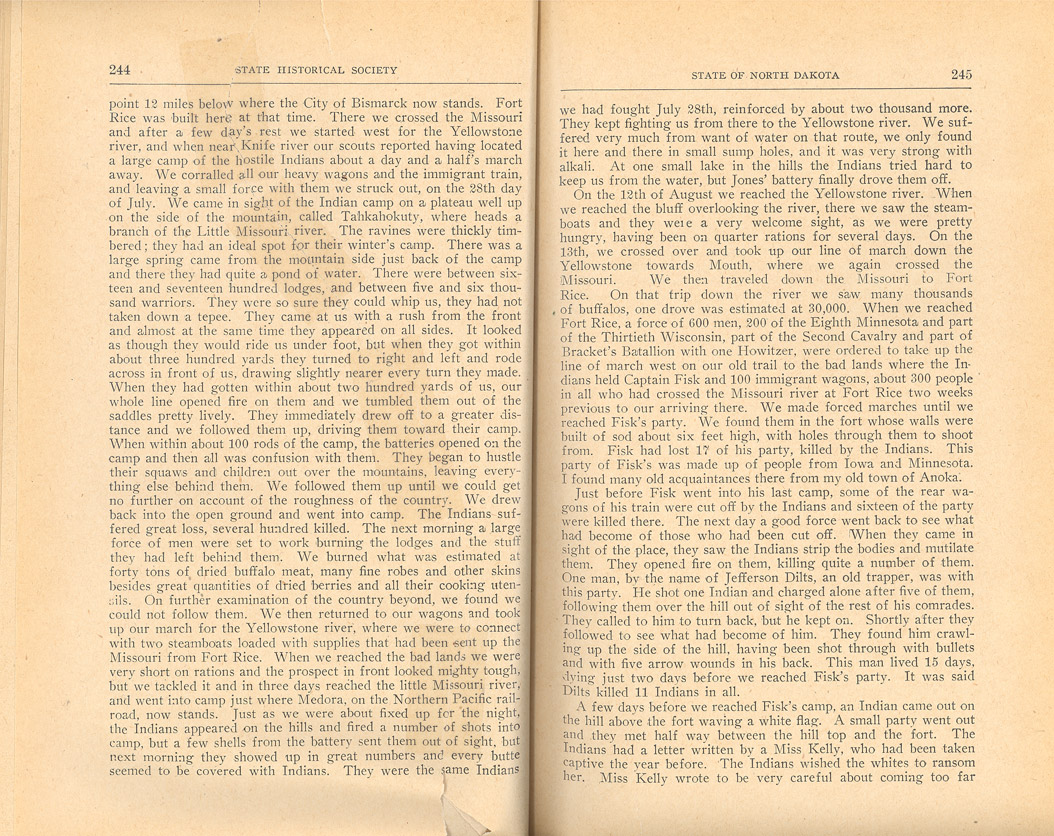

We know less about William E. Seelye (Document 2). He was a Minnesota resident and served as a private in Company A, 8th Minnesota Infantry. Like Paxson, he was a volunteer for the Army. He served with his unit at the Battle of Killdeer Mountain. He apparently stayed in Minnesota and claimed land there (perhaps as part of his military bonus) in 1872. Seelye’s memoir is different from a diary. He wrote it much later in life (it was published in 1910.) Memoirs are important, but because of the passage of time, there may be errors of memory. Like Paxson, Seelye over-estimates the number of Dakotas who died in the battle. However, his memoir corroborates, or supports, the diary of Lewis Paxson.

Sources: W. E. Seelye, “Early Military Experiences in Dakota,” Collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota Vol. 3 (1910): 242-246; Lewis C. Paxson, “The Diary of Lewis C. Paxson, 1862 – 1864,” Collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota Vol. II No. 2 (1908): 102-163