Schools in Dakota Territory and North Dakota were (and still are) governed by state law. Laws directed that students learn (Document 1) to read, write, and “cipher” or do arithmetic. By the time North Dakota became a state, students were also required to study geography and history. After 1890 students also studied “hygiene” which taught them about the anatomy and physiology of the human body. As part of their study of hygiene, students had to learn about the effects of alcohol and drugs on the body. The legislature considered this area of study so important that teachers who refused to teach “hygiene” studies could be fired from their jobs and lose their teaching certificate. (See Document 2.)

As a frontier territory with a widely scattered population, the earliest school laws did not require students to spend a lot of time in school. Twelve weeks was the minimum requirement for many years. School district superintendents tried to schedule school sessions at a time when children’s labor was not needed on their parents’ farm. However, many schools did not meet during the coldest months of winter. By 1917, the state school superintendent encouraged schools to meet for nine months each year, though the law required only seven months of school. Still, some school districts did not meet even that minimum standard.

In the territorial period, there were very few high schools, except in the larger cities. Fargo opened a high school in 1878; Bismarck’s high school opened in 1883. Though schools were open to five-year-old (See Document 3) students, there was no kindergarten. The youngest students started in first grade.

School discipline (See Document 4) was both difficult to maintain and very severe. Teachers were often as young as 16. Many had graduated from 8th grade the year before they began teaching. Young girl teachers often had male students who were older and bigger than they were. They had trouble disciplining “big boys” who were intent on causing trouble. The law supported these teachers, however, by making it possible for disruptive students to be charged with a misdemeanor crime.

The legislature made a commitment to replicating traditional American culture in all rural and urban schools. Though the territory had already attracted many settlers of foreign birth, all children would be instructed in the English language (See Document 5) and were required to study American history. Acculturation of the immigrant family to American culture often occurred through the school children.

In 1890, the legislature declared the Bible to be a non-sectarian book (See Document 6) which means that it was not attached to a particular church denomination. The legislature encouraged teachers to read the Bible in school, but acknowledged the Constitutional separation of church and state in three ways. First, the teacher was not allowed to offer a religious interpretation of the Bible. Second, pupils were not required to read the Bible or attend class during the reading. Third, though the Bible was “non-sectarian,” the law stated that it was a good source of “moral instruction.”

Most of North Dakota’s rural school-age children worked on their parent’s farm. These jobs did not fall into the legal category of child labor. However, if a child worked (See Document 7) in a mine or a factory, the law required that the business owner to release the child from work to attend school. However, the law also allowed for a business owner to go to the superintendent of the school district to obtain a certificate stating that the child had already attended 12 weeks of school that year.

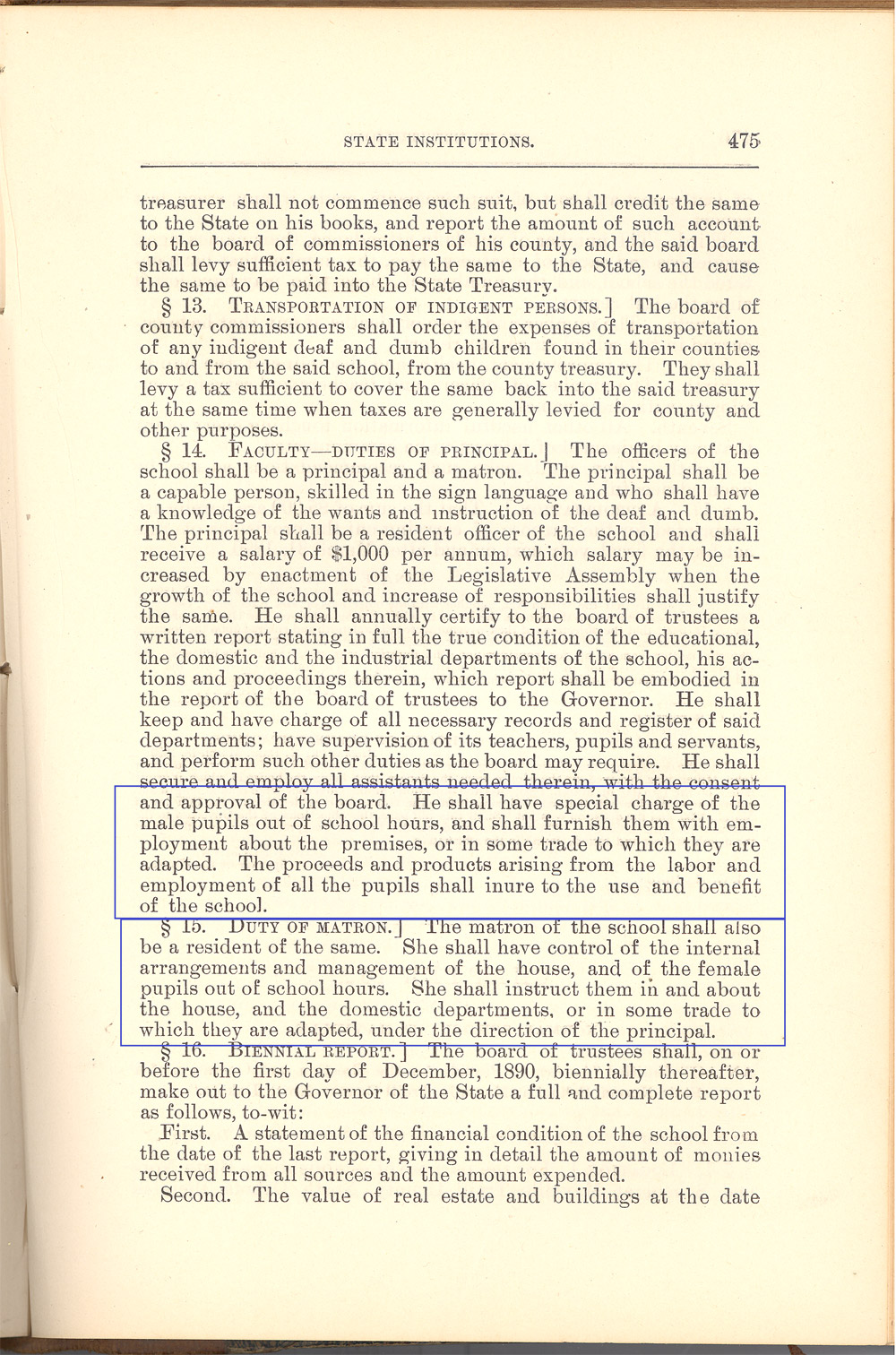

The new state of North Dakota also established a school for children with hearing impairment. [Doc 8]The school was called the Institute for the Deaf and Dumb. Today this school is called the North Dakota School for the Deaf. Anson Spear, a hearing-impaired young man who had studied at schools for the deaf in other states, urged the legislature to pass this law. Spear believed that in addition to academic instruction (reading, writing, and arithmetic) deaf students should be trained in vocational occupations. The law is vague about how boys should be trained. However, a couple of years later, boys at the School for the Deaf learned the trade of printing. Girls were trained in housekeeping, cooking, and other “domestic arts.” The law was generous in recognizing that some of the students at the School for the Deaf might come from impoverished families. The state provided clothing for the students if there was no parent or guardian to support her or him. A deaf child of a poor family was transported to the school at the expense of the state.

Why is this important? What children study in school is a good way to measure what a society valued. Because these children lived in a democracy, it was important for them to know the history of their nation and state, the geography that might affect how laws were written, and especially, how to read and write.

These courses not only prepared the students to participate in a democracy, they prepared them to be productive workers. Even students with disabilities were “trained” to be employable, though in the 19th century, no one expected them to go on to high school or college.

Schools were also the primary level of participatory democracy in the United States. People attended school board meetings, ran for a seat on the school board, and voted on school issues. Rural schools, especially, were places where students learned and parents practiced democracy.