Following the Civil War (1862-1865), the Army reduced the numbers of soldiers and officers. The smaller Army of experienced soldiers then turned its attention to the West. On the Great Plains, Indian tribes resisted the arrival of soldiers, farmers, railroads, and towns.

Officers, ranking from second lieutenant to general, commanded enlisted men at the forts in Dakota Territory. Their duties varied. Sometimes, they were leading soldiers who were guarding railroad survey or construction crews. At other times, their duties involved completing paper work and supervising enlisted men on fatigue duty. Off duty, many officers liked to hunt bison, prairie chickens, or prairie wolves. (Document 11.)

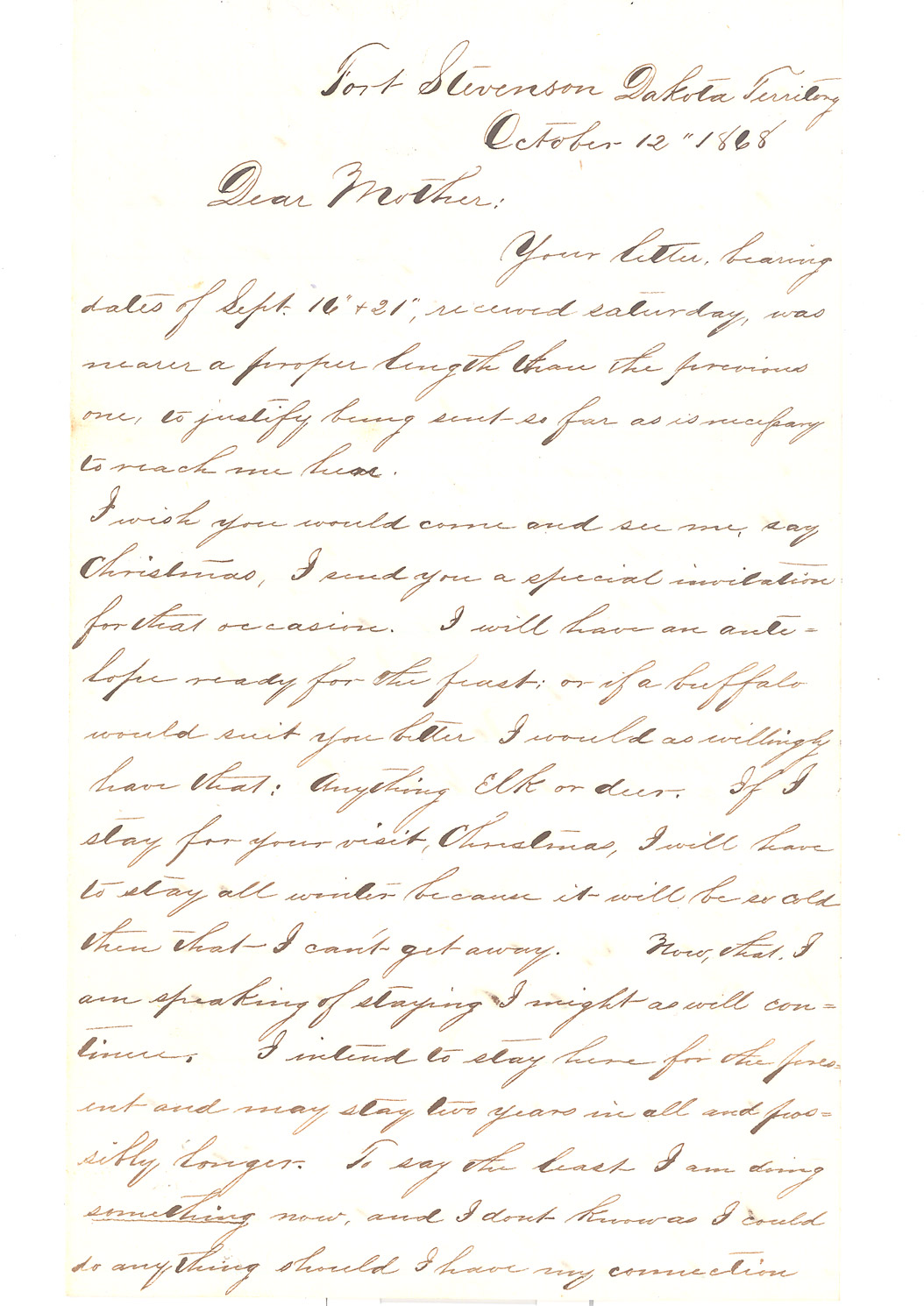

Document 11

July 25, 1868 Dear Mother,

. . . You give such a fine detail of the garden that I almost want to be home. I certainly should be if I could make as much money there as here. This [military life] is not making money very fast – but it is doing something.

We have some fresh vegetables here. The sutlers [post traders] have a garden and there are company gardens. We have had onions radishes salad peas etc. I have written so much about the place Indians etc that I will say no more at this time about them except that the whites are meaner than Indians Some halfbreeds [people whose parents were both Indian and non-Indian] came in today with their wives & children entirely out of food. The post trader put his flour immediately up from $15 per hundred [pounds] to $20.

A man finds Indians starving he tempts him with the sight of bread and then buys his property for a song and call that sharp. It is no wonder they wont keep a peace.

. . . . . . Fort Stevenson D. T.

Oct. 4 1868

There is a prospect of me going to Fort Buford as medical officer – for a detachment which has been ordered there and return with a detachment coming from there here to be mustered out. I don’t know as this will be the case but have been told that it might be and asked if I was willing to go and of course I said ‘Yes.” I would like to go as it will give a chance to see some wild country and perhaps to get some curiosities.

I am ready to leave the army as soon as I hear of a place for private practice with a good prospect of success but until then or something else happens I will stay win my present position if I can. . . .

. . . .

October 12, 1868

. . . I wish you would come and see me [at] Christmas, I send you a special invitation for that occasion. I will have an antelope ready for the feast, or if a buffalo would suit you better I would as willingly have that: anything Elk or deer. If I stay for your visit, Christmas, I will have to stay all winter because it will be so cold then that I can’t get away. Now that I am speaking of staying I might as well continue. I intend to stay here for the present and may stay two years in all and possibly longer. To say the least I am doing something now, and I don’t know as I could do anything should I have my connection with the army dissolved. It is this something for nothing argument that determines me to stay. I am receiving as I have written before perhaps about $134 per month. I think I will clear out of this $100 a month at least, making $1200 a year, and that amount don’t grow on every bush. It is the money and nothing else that is keeping me here.

I think Military life is about the biggest humbug imaginable. It was aptly compared the other day, by Lieut. Hooton to waiting for the cars at a depot. Several of us were sitting together when after a time he broke the silence with a yawn and said “Oh well the cars will be along by and by.” . . .

. . .

Nov. 10, 1868

Your letter of the 7th ultimo [last month] with Mary’s appendix came last wednesday and was very welcome I assure you. I had just returned from Ft. Buford but two days before and did not find any letter waiting from you . . .

I spoke of going to Buford. Co[mpany] “I” 31st In[fantry] was ordered to that post and I was sent as medical officer. A herd of cattle were taken up at the same time to replace those the indians captured last Aug. The journey was completed without seeing a single hostile indian, luckily. The distance is 150 miles and was made in eleven days going up. Started from here Oct 16” & reached Buford Oct 26. At Buford I met Dr. Woodman who was my companion on the way out from New York. We started back Oct 28” and arrived her Nov. 2nd making the return trip in five days. The weather was good although late in the season.

The novelty of my first experience in camp life made the trip rather pleasant than other wise. The only game I saw on the whole trip was antelope which were quite plenty. One of the scouts (indian) said he saw a grizzly bear but was afraid to attack it. It is said to be impossible for so large a party to see much game, the scent is given so far and so much noise is made that wild animals take the alarm and keep secluded. So I have hardly a memento of the trip. Buford is opposite the mouth of the Yellow Stone River and is as you see north as well as west. You can look at your map and see just where I have been.

. . . Don’t put any fruit in the box as it will not pay. I get all kinds of canned fruit preserves jellies pickles etc in the Commissary at wholesale prices. Express the box about the middle of February or between so it will get to St Louis in time to take the first boat up the Missouri

. . .

Nov. 10, 1868

. . . I have got along finely so far although I have had to spend more money than I thought I would . . . Since I left home have spent about $300 but part of this was traveling. My mess [meals] bill runs about $30 a month washing $5 “Striker” to take care of room $3 to $5 and $5 for the cook. So you see it is impossible to get along for less than about $45 a month without any incidental expenses, not even lights. To offset against this is some [medical] practice which has brought me a little over $100. I think there is no doubt but I can clear $1200 in the course of a year, as I wrote some time ago. . . .

We are waiting for Saturday’s mail to learn the result of the election but expect to have to wait still a week longer . . .

. . .

Nov. 22, 1868

. . . Yes Ma we are all aware that a president has been virtually elected, but we don’t know who it is, but hope to know Saturday (in five days). We didn’t get excited because we knew we couldn’t help elect the president, and couldn’t see anybody that could. Nobody in the territories can vote for president, they only vote at the territorial elections. They have a representative in Congress but he cannot vote he only advocates (pleads) their cause. The only place I can vote is in Conneaut [Ohio]. . . .

. . . a lot of “our country” potatoes brought up [river] from below in wagons over land. They sell to officers for 90 cts a bushel. That is better than to pay the sutler $6 . . .

Yesterday Lieut. Walborn died; he is another victim of alcohol. He was but 24 years old & leaves a wife and two little boys. They cannot get to the states until spring. Their home is in Philadelphia. . . .

. . .

May 25” 1869

I received my pay on the 15” instant [this month] up to the last of this month, it being after deducting income tax eight hundred and ninety two ($892) dollars. I took a draft of seven hundred ($700) dollars, which I will send to you. I have also concluded to send one hundred ($100) more in currency, which will be expressed to you from Middletown Pa. Mrs. Walborn is going home and will carry it to that place sending it to you from there. . . . I wrote you some time ago that the 31” and 22” Infantry are consolidated forming the 22” Regiment and is commanded by the Colonel of the old 22”, [Brevet] Gen’l Stanley. . . .

For the consolidation the assignment of officers was left to Gen Stanley who, although acting very arbitrarily, has selected upon the whole an excellent lot of officers. His motto being on the whole to select able and temperate men. The order from the War Department says the senior officers fit for active service are to be retained, while Gen Stanley has retained many junior officers. There is much hard feeling from those who felt entitled to be retained, and the juniors who are retained feel insecure for the present. But it ain’t my fish. It don’t affect me.

Sunday was a very hot day. Yesterday and today were cool and stormy especially today. The rain will be good for the company garden. The river is now quite high and steamboats are continually arriving.

I don’t expect to send home any more money this summer if I come home this fall -

Good bye. Your boy

John V. Bean

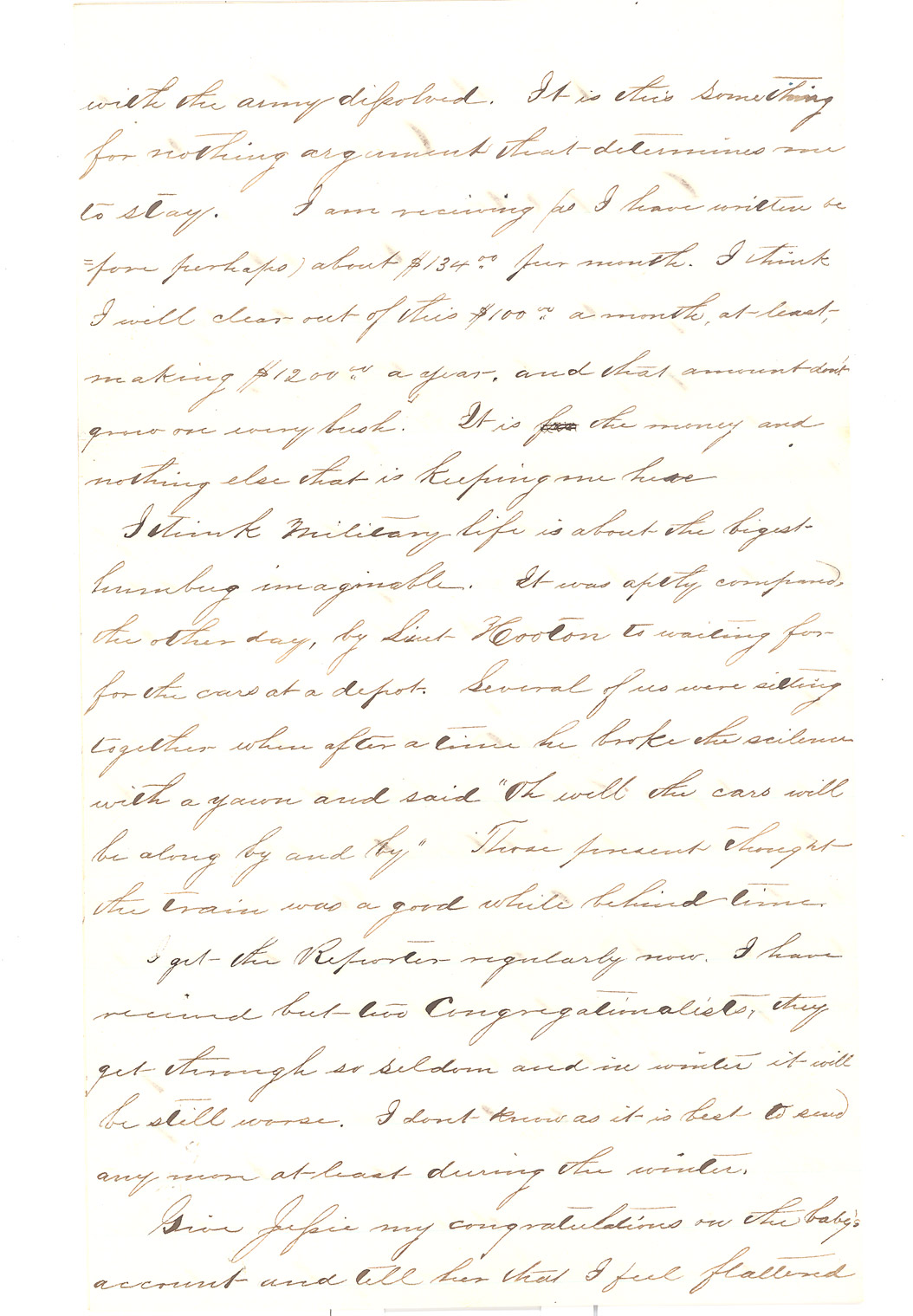

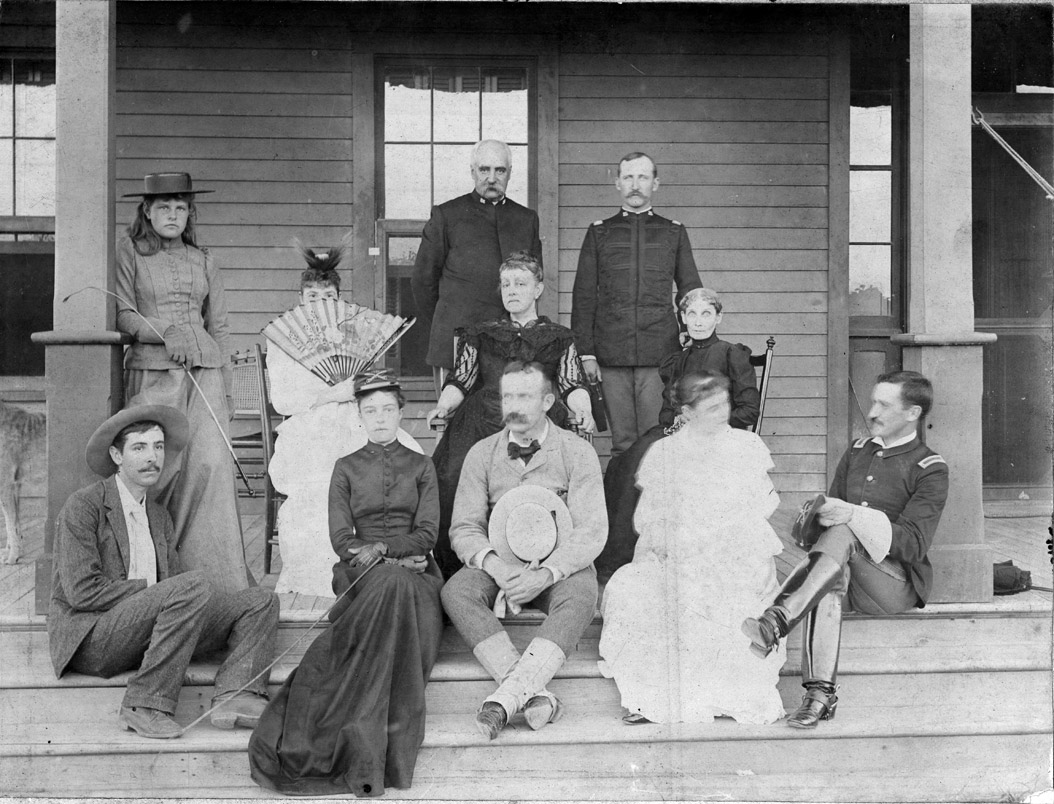

The behavior standard for officers was higher than for the enlisted men. They were to conduct themselves as gentlemen at all times. Their social relations were much as they might have been in a big city. (See Image 13.) They made social calls on other officers and their wives, arranged for “theatricals,” or plays, and hosted other officers for elaborate dinner parties. (See Image 14.) Their meals were prepared from canned goods, wild game, or garden produce raised by enlisted men.

After the Civil War, officers were encouraged to bring their wives and children to distant, isolated posts in the west. With the presence of families, a military post became much like a small town. Children had the run of the post and often found friendly enlisted men to follow around all day. Few posts had schools, though sometimes an educated non-commissioned officer (a sergeant) might teach school for the post’s children separately from classes for undereducated enlisted men. Family pets, especially dogs, roamed the post as they pleased.

Musical events were an important part of social and military life. Families enjoyed an evening concert if they were stationed at a post with a band. Many officers’ wives remembered fondly the song “The Girl I left Behind Me” which was often played as the soldiers marched away from the post. (See Document 12.)

Document 12

Many Army forts had a band which played regular concerts and whenever the troops marched away from the post. “The Girl I Left Behind Me” was one of the most popular songs at the Army posts in Dakota Territory. The Seventh Cavalry under the leadership of Colonel George Armstrong Custer was fond of the Irish tune “Garry Owen.” Listen to these tunes online: “Garry Owen” and “The Girl I Left Behind Me.”

Officers had few chances for advancement in the Army in the late 19th century. The Army was trying to reduce costs, so promotions were rare and many officers felt frustrated at the lack of advancement. Officers, however, took pride in service to their country. Many believed that they were far more financially secure in the Army than they would have been in post-war civilian life. Jobs in the private sector were hard to find in those years.

Sometimes the posts were in danger. Fort Rice (built in 1864) was attacked several times by Dakotas. Though the soldiers successfully defended the post, women felt they and their children were in danger of being captured or killed. There were many risks for officers’ families, but many men preferred to keep their wives and children nearby.

Officers learned a lot about life on the Great Plains during their assignments. Some, such as Fort Rice surgeon Frank Slaughter, along with his wife and other officers, studied Dakota language and visited nearby sites of ancient Mandan villages. They developed opinions about the “Indian Problem,”The “Indian Problem” was a term commonly used in the 19th century. It was a sort of code term to cover a range of issues. The Indian Problem covered conflict between the U.S. government and American Indian tribes over control of the land; assigning Indian tribes to reservations; and educating the children of American Indians. To some people, the solution to the “Indian Problem” was establishing reservations. Others thought that issues of cultural and territorial conflict could only be resolved by military action. Other people, often grouped under the label “Friends of the Indian,” believed that Indians could be educated and assimilated, which means to change their way of life from their traditional culture to a culture similar to that of Anglo-Americans. and wrote home to friends and family in the states about why Congress and the President had taken the wrong path to solving the conflict. Most officers preferred a “military solution.” Some officers believed that it would be necessary to kill (exterminate) most or all Indians. General John Pope, who oversaw some of the earliest military efforts on the northern Great Plains said at one time: "It is my purpose to utterly exterminate the Sioux. They are to be treated as maniacs or wild beasts, and by no means as people with whom treaties or compromise can be made."

However, most officers held a more humane view. Officers who lived on western Army posts personally knew American Indians as friends or enemies. These officers believed that a strong military presence at reservations would be sufficient to prevent violent conflict between whites and Indians and protect Indian reservation land from white settlers. Ironically, the officers sadly recognized that in order for peace to prevail, Indians would have to give up most of their land and many aspects of their culture. General Pope, who many people thought was the most humane of Army officers, also said: “The Indian, in truth, has no longer a country. His lands are everywhere invaded by white men; his means of subsistence destroyed and the homes of his tribe violently taken from him; himself and family reduced to starvation . . .”

Army officers led soldiers in the opening of the northern Great Plains to settlement. Some officers believed that the cold, dry country would never be successfully settled by farmers. Other officers saw opportunity and, like enlisted men, settled in the land of their military service.

Why is this important? Army officers brought their upper class education and culture to the West. Officers and their wives became important social and political leaders in the new towns of the West. Their families required churches, schools, and other social organizations which then took root in the new communities that grew up around Army posts. Officers often demanded that the federal government craft a more humane and consistent policy toward Indian tribes.