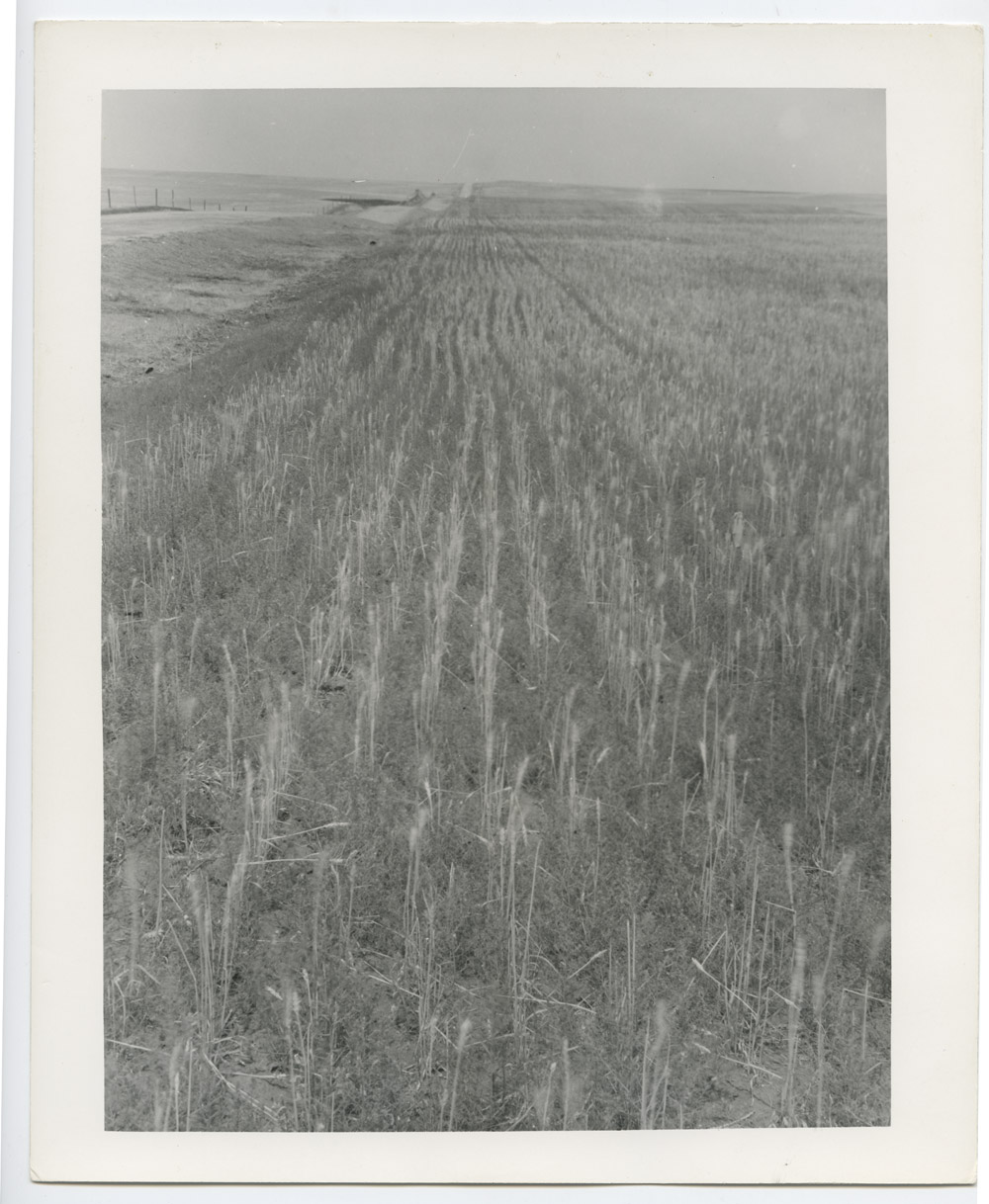

DroughtDrought is officially defined as “continued lack of moisture, so serious that crops fail to develop and mature properly.” However, the severity of drought depends not only on rainfall, but on temperature and wind. High temperatures and high winds tend to pull moisture out of crops. When wind, heat, and lack of precipitation combine for a long time, the drought can be very severe. is a serious climate issue in North Dakota. It can cost farmers an entire summer’s crop. Drought can force ranchers to sell their livestock because there is no grass for feed. Drought can reduce surface water in ponds and rivers.

Drought, however, is also very difficult to identify. Some weather experts call drought a “creeping phenomenon” because it is very hard to tell when it starts and when it ends. In addition, drought may be localized. A county may be suffering from drought while the neighboring county has sufficient moisture.

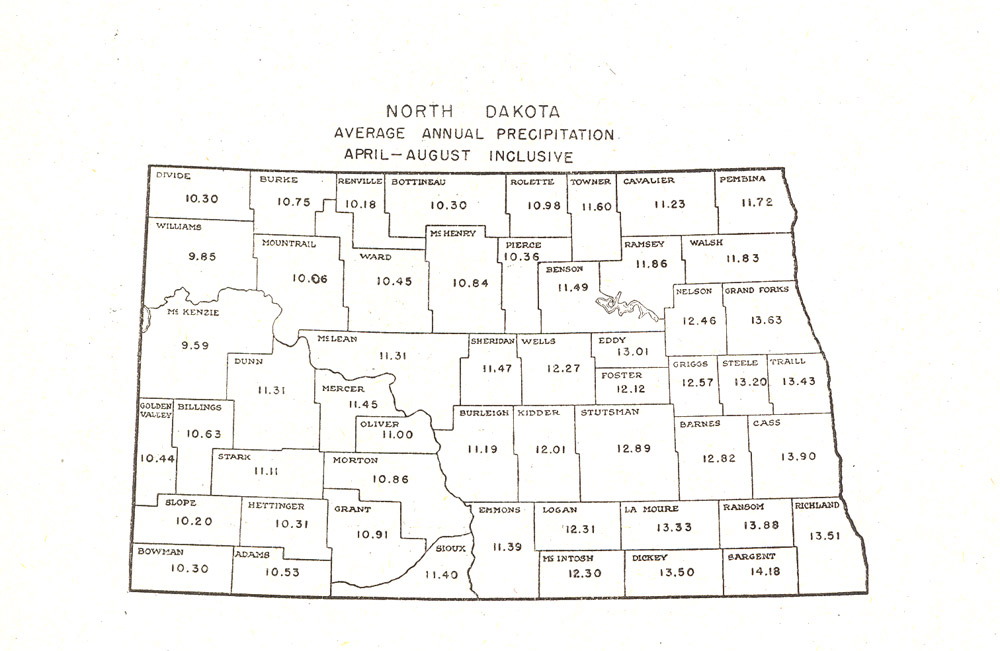

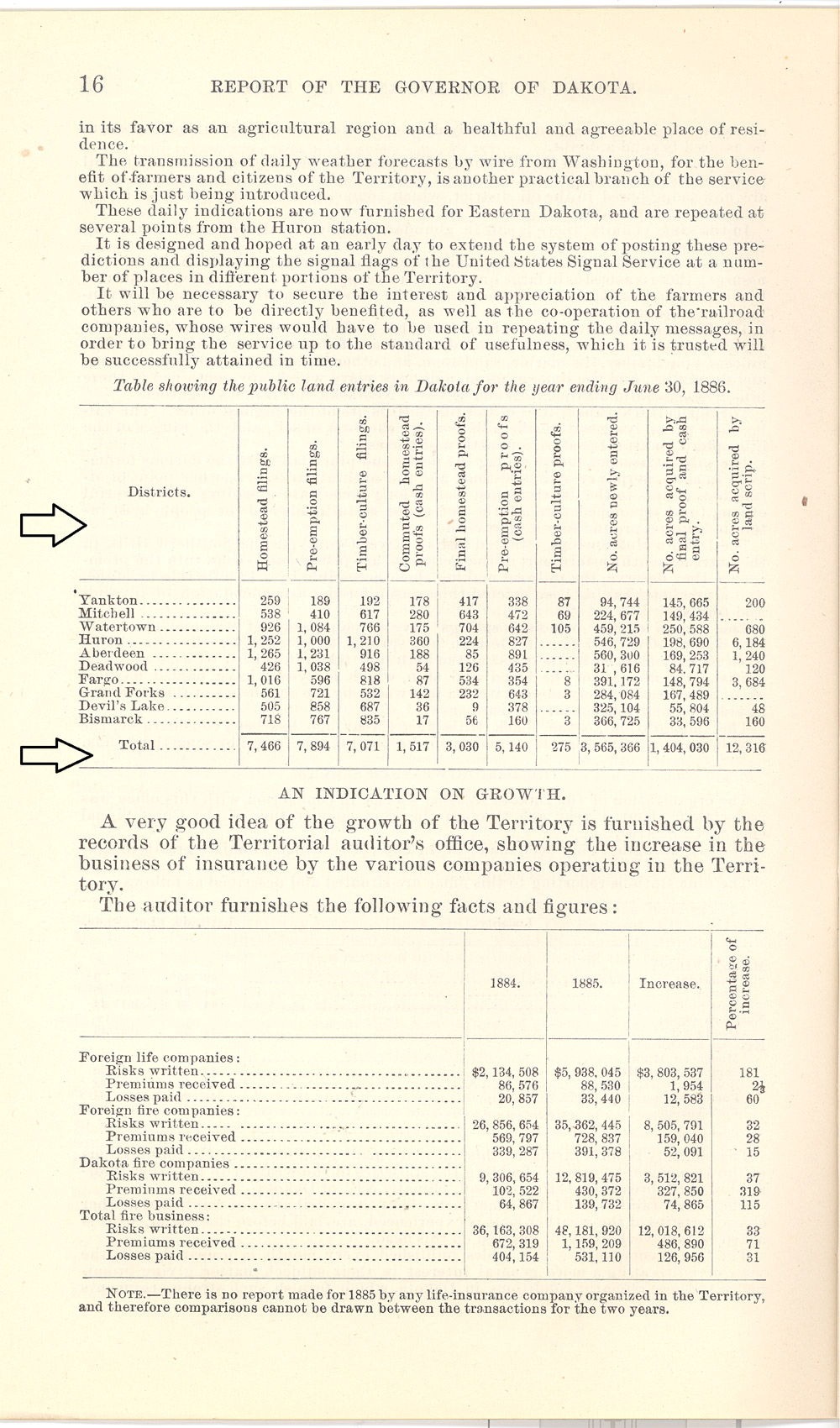

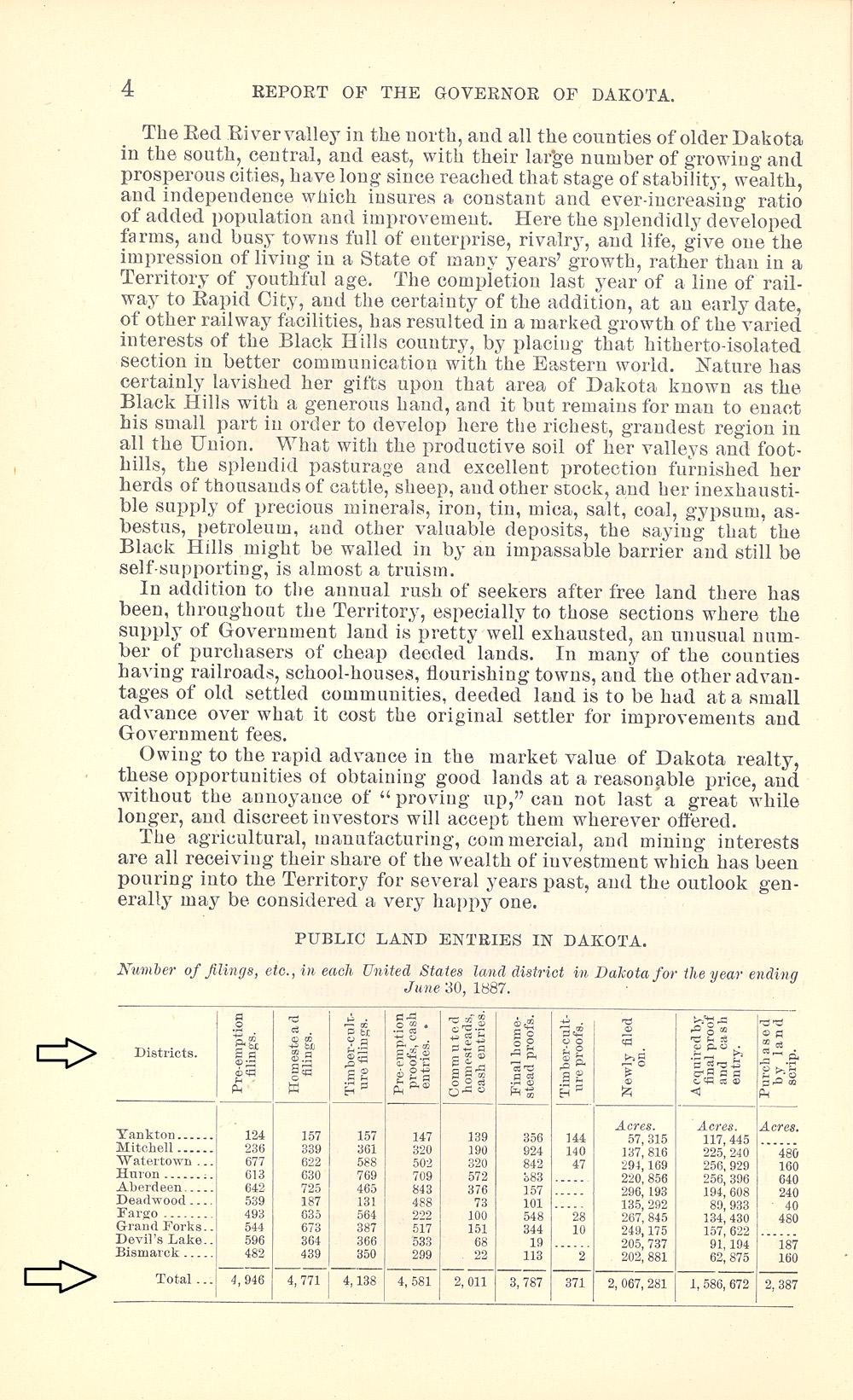

The average amount of moisture expected in North Dakota each year is just a little over 17 inches. The eastern part of the state averages more precipitation than the western part of the state. However, any part of the state can experience droughts. The droughts can be brief and localized, or severe and widespread. The following chart shows how often drought appeared between 1889 and 1962 in North Dakota.

|

Western 1/3 of North Dakota |

Central 1/3 of North Dakota |

Eastern 1/3 of North Dakota |

|

|

Number of years between 1889 and 1962 with less than 17 inches of rain |

55 |

38 |

12 |

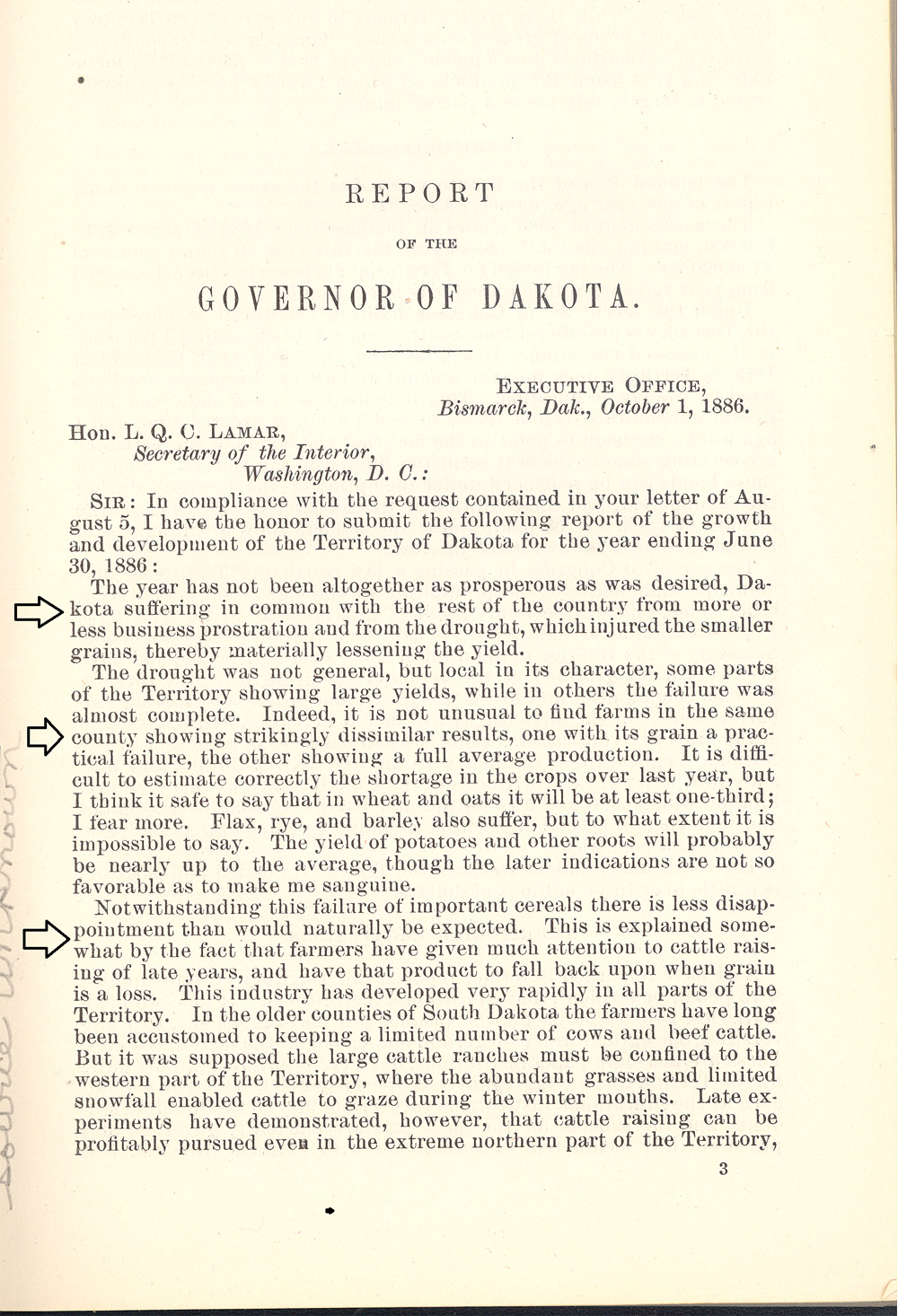

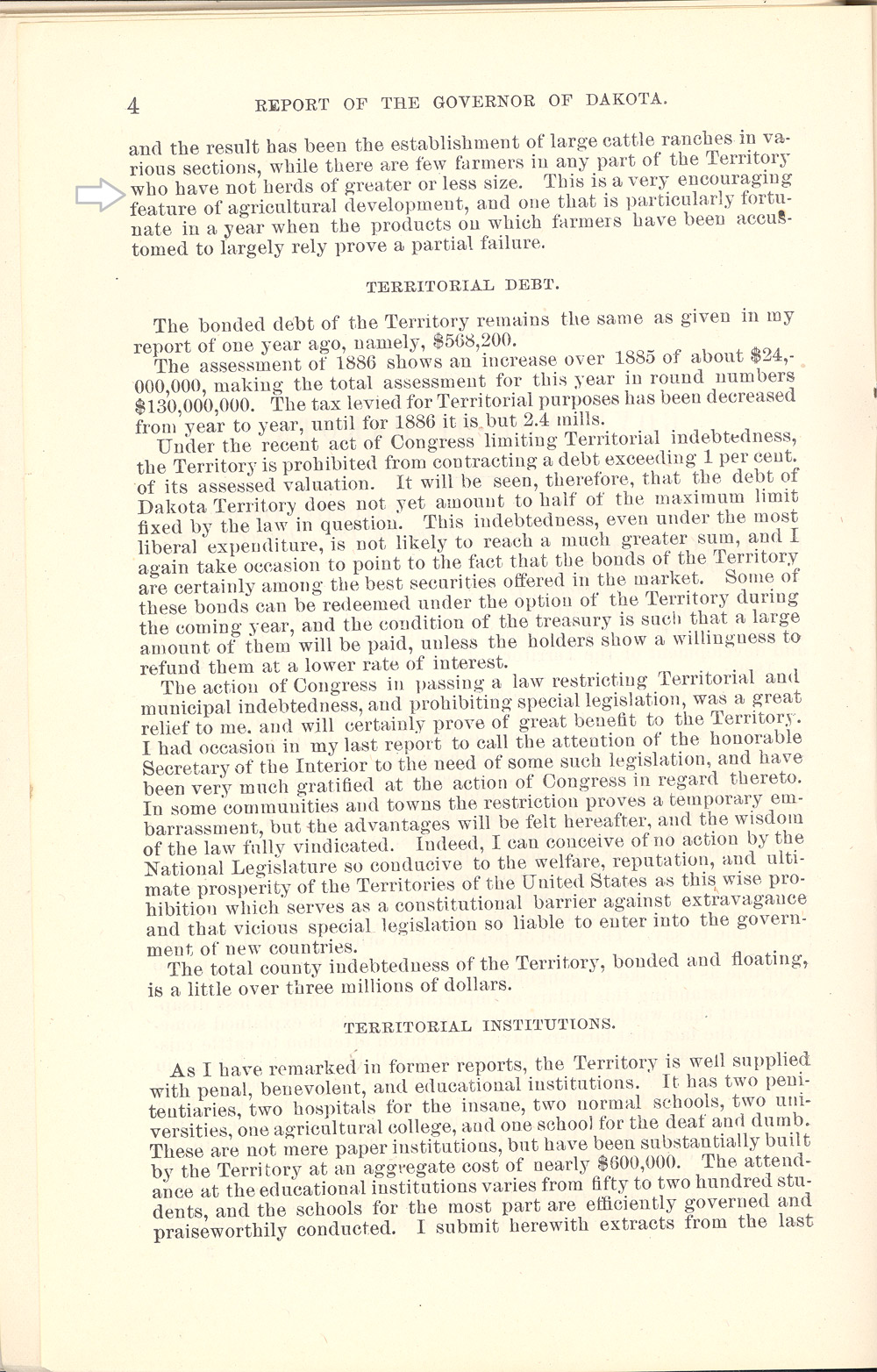

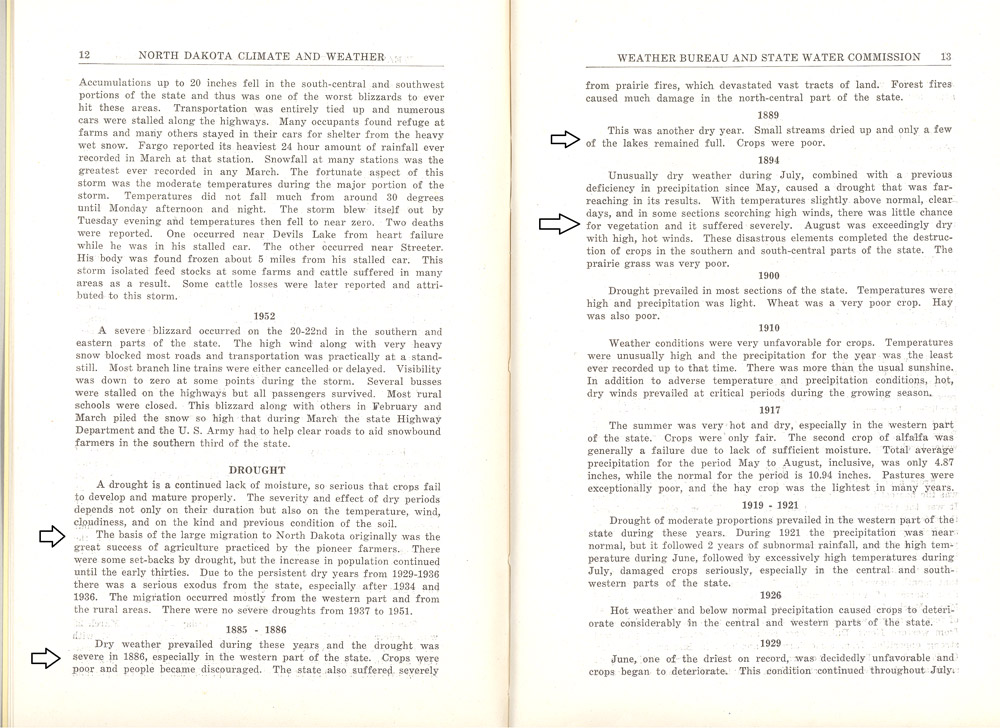

There were several years of drought between 1870 and 1930. But there was only one drought that lasted a long time. Between 1886 and 1895, there were four years of severe drought and a few years of moderate drought. (See Document 7)

The drought of 1886 was particularly important because it brought an end to the Great Dakota Boom. During the boom years, thousands of people moved into northern Dakota Territory to homestead or purchase land. The early years of settlement were a time of plenty of rain. However, in 1886, the wheat crop ran about one-third less than expected. When drought persisted and crops failed several times, some people left their farms. Fewer people wanted to move their families to Dakota Territory. Since farming was the most important occupation in Dakota Territory, the drought served to slow down immigration. (See Document 8)

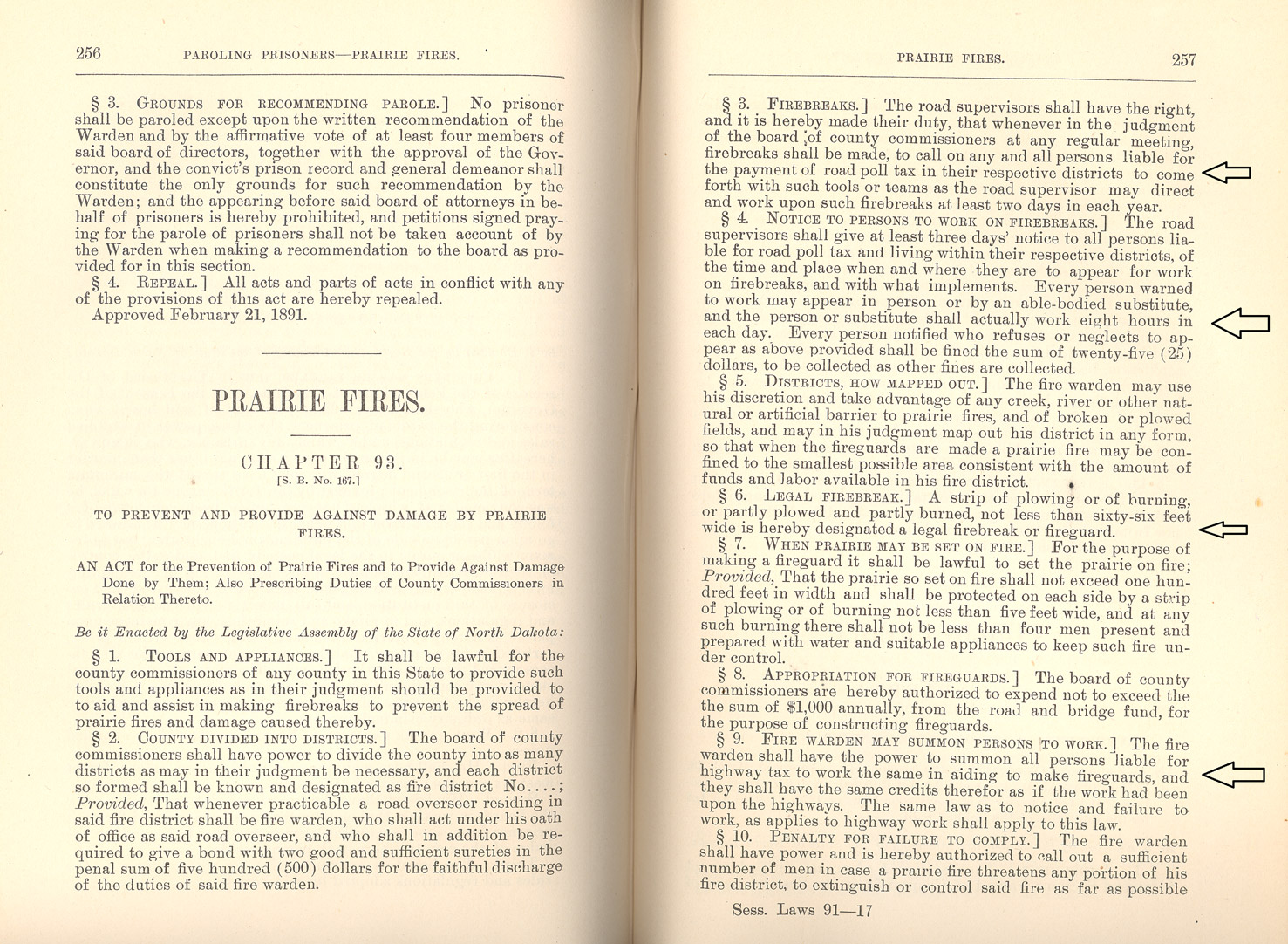

Drought keeps bad company. One likely problem associated with drought is prairie fire. Prairie fires were common in early spring and late summer almost every year during the settlement era. During periods of drought, however, prairie fires burned more frequently destroying more acerage. (See Document 9) Prairie fire was a common and dangerous enemy to farmers and towns in North Dakota. In order to prepare communities to suppress prairie fires, the legislature passed a law in 1893 explaining exactly how counties should be organized for fighting prairie fire. (See Document 10)