Between 1867 and 1887, the Dakotas faced increasingly difficult agency rules. The first agent, William Forbes, asked the Dakotas to scatter from their villages onto individual homesteads. The second agent, James McLaughlin, tried to force the Dakotas to take up the culture of Anglo-Americans by giving clothing instead of blankets with the annuities. (See Image 16) McLaughlin tried to limit the power of the chiefs by giving them no more from the annuities than anyone else received. More and more settlers in the Devils Lake region were looking over reservation lands. The agent, John Cramsie, asked for a survey of the reservation in preparation for opening the “surplus” lands to settlers.

When the Dawes Act became law in 1887, the Devils Lake Reservation was approved for allotment immediately. Allotment forced the agent to deal with the reality that 64,000 acres of reservation land had already been claimed by non-Indian homesteaders. The federal government had an obligation by treaty to protect reservation lands. The Dakotas negotiated with the government and accepted payment of $345,000 for the 64,000 acres that had been illegally taken from them. That amounted to $5.39 per acre. The sale of the 64,000 acres reduced to 166,400 acres the portion of the reservation available to the tribe.

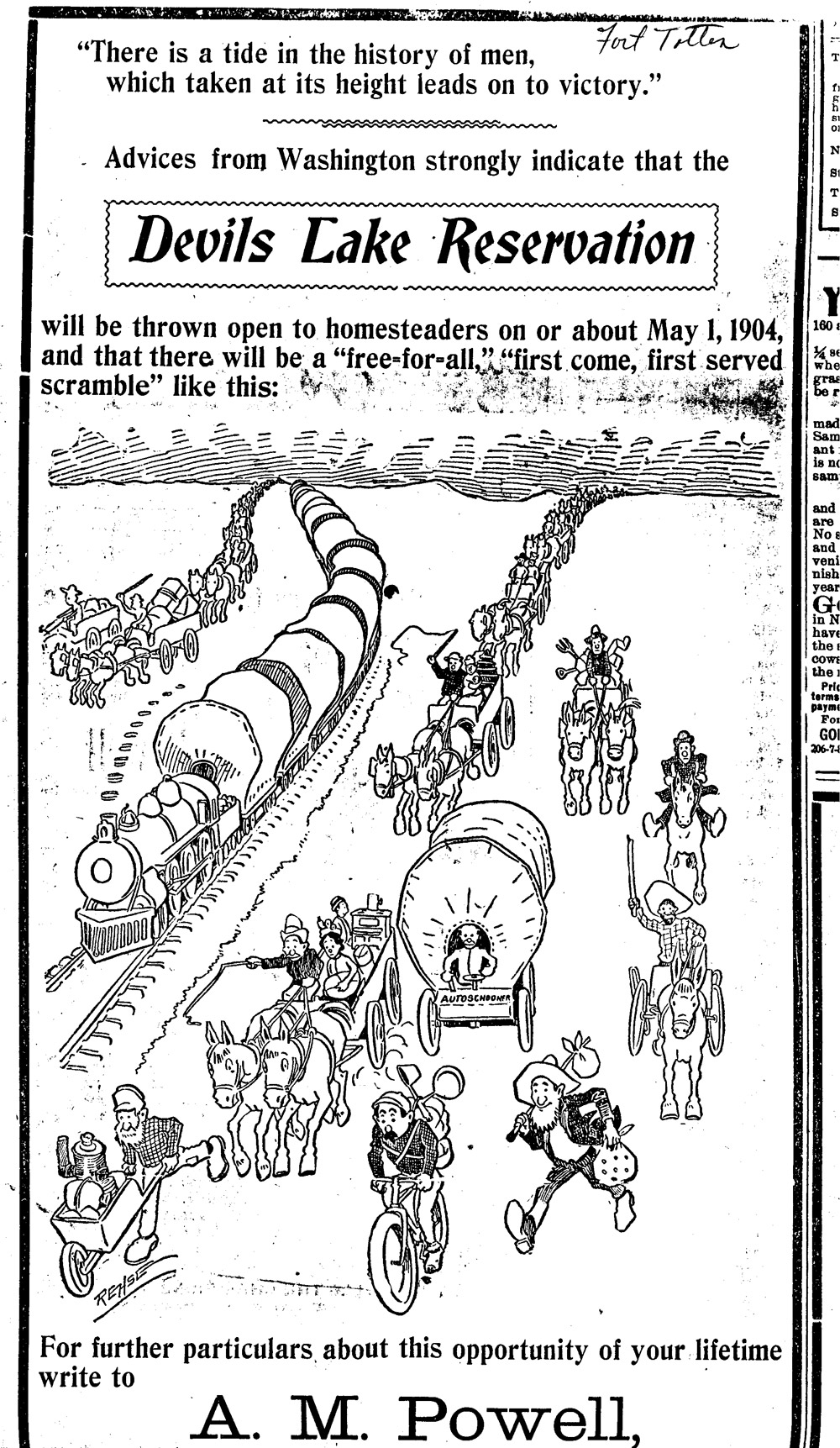

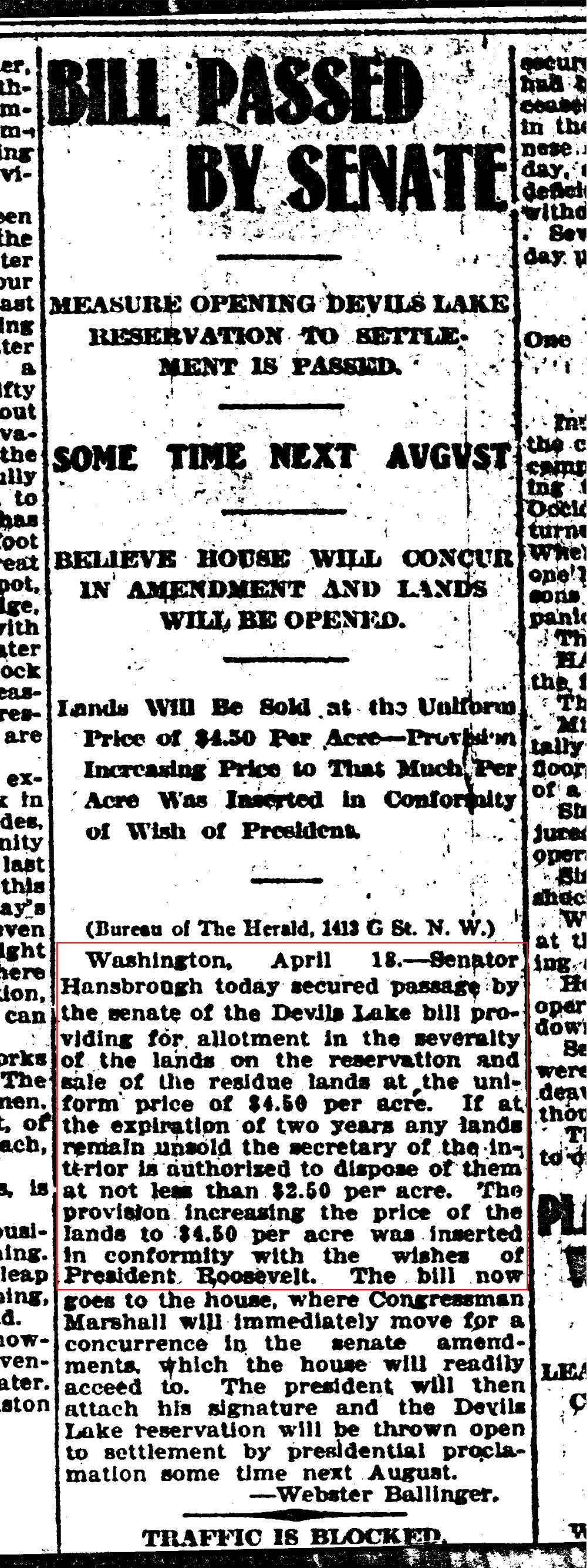

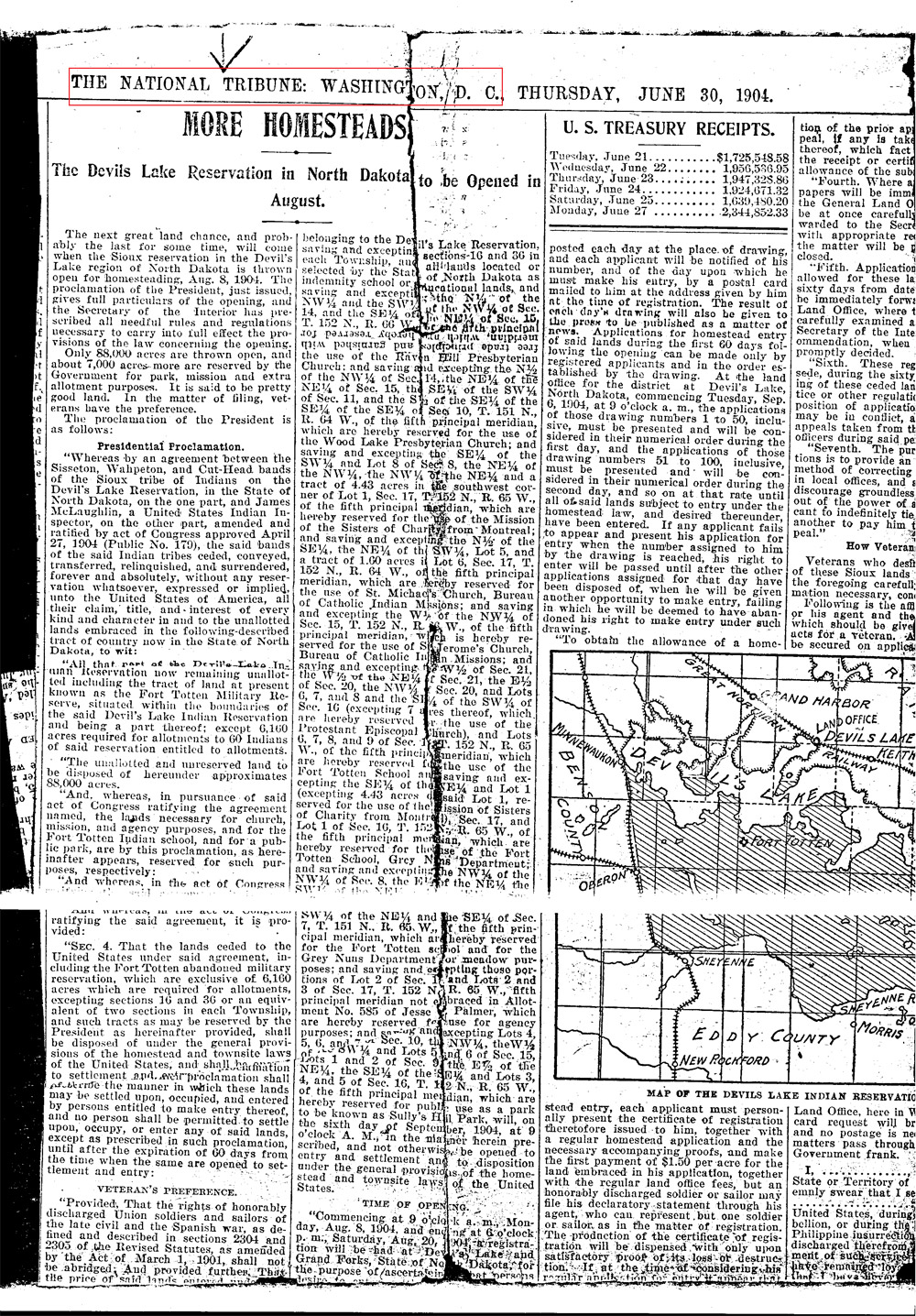

In 1904, 100,000 acres of unallotted reservation lands were officially opened to settlement (See Document 24).

Non-Indians who wanted reservation lands now had to pay an average of $4.50 per acre (See Document 25). When the allotment program officially ended in 1934, the Dakotas of Devils Lake Reservation (Mni Wakan Oyate) owned only a little more than 50,000 acres (See Document 26).

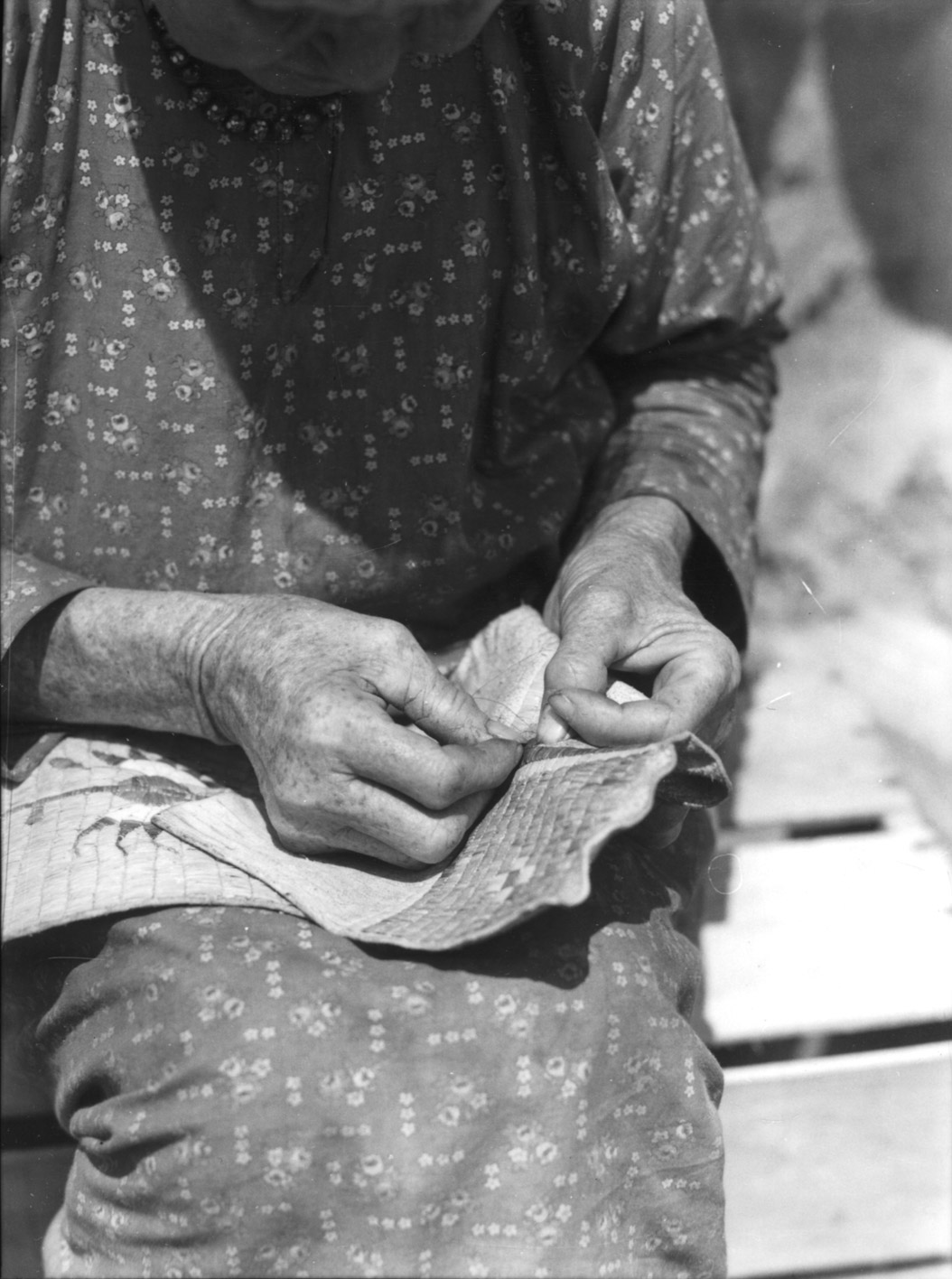

When the Dakotas chose their allotments, they looked for land near their relatives. In this way, they formed small communities of Sissetons, Wahpetons, and Yanktonais. These communities became towns such as Tokio and St. Michael. Living on allotments or in town, the Dakotas tried to maintain their traditions within the framework of reservation life (See Image 17).

Why is this important?Like the other reservations in North Dakota, the Mni Wakan Oyate have lost large amounts of land. Though they protested the taking of these lands, without citizenship they had few legal rights to interfere with the government’s plan. The Supreme Court decision, Lone Wolf vs. Hitchcock, further enhanced the power of the federal government over reservation lands.

The loss of land contributed to the poverty on the reservation. The interspersing of non-Indian land with allotted land led to the loss of traditional culture. Nevertheless, many Dakotas had good relationships with their non-Indian neighbors.