Around 1450 A.D., perhaps a little later, some Mandans (they called themselves Nu’eta) built a village on the banks of the Missouri River about 30 miles south of Mandan. It was one of a network of Mandan villages along the Missouri River. The Mandans lived at Huff Village for a short time, perhaps 20 years. However, when they came to this place, they built a very well organized city where about 1,000 people lived.

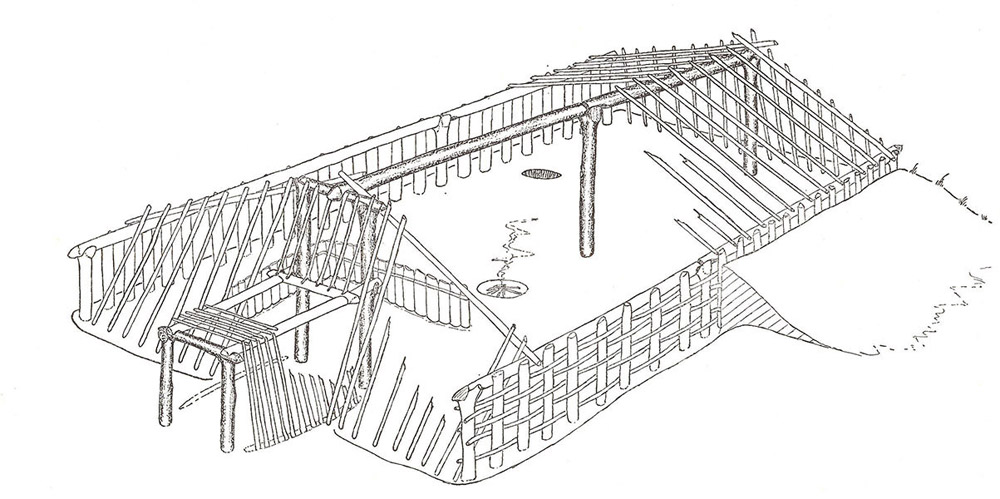

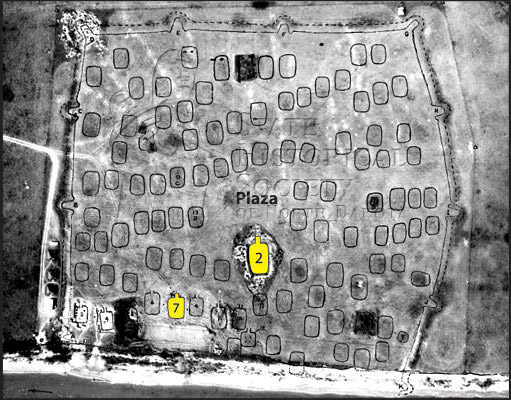

Huff village houses were rectangular in shape and built of log and earth. (See Image 1.) A palisade (wall) made of upright logs surrounded three sides of the village. The fourth side was open to the Missouri River. The palisade included 10 bastions (an extension of the wall) where village residents could fight off enemies or spot bison on the prairie. (See Image 2.)

Life in the village revolved around gardening and hunting. A couple of times a year, the entire village went out to hunt bison. Men did most of the hunting, while women dried the meat, tanned the hides, and prepared other parts of the bison for many different uses. Near the village, women raised corn, beans, squash, and a few other vegetables in gardens.

The Nu’eta organized their village life by the seasons. In the spring, as river ice began to move and waterfowl flew northward, the men played the hoop and stick game which brought good luck in hunting bison.

When the women of the Goose Society saw the signs of spring, they performed the Corn Dance. Each woman held an ear of corn and danced while men played musical instruments. The ceremony honored the “Woman Who Never Dies,” a Mandan sacred spirit who encouraged plants to grow in the spring. Following the ceremony, women prepared and planted their gardens. Though planting was hard work, the women sang songs to make the work easier and to encourage the plants to grow well.

Spring was also the time for gathering wood. Drift wood floated down the river at flood stage. Men and boys swam out to retrieve floating wood. They dragged logs to shore to dry for firewood.

During the summer, women and children gathered juneberries, chokecherries, and plums. In mid-summer, they dug prairie turnips, also called pomme blanche (Psoralea esculenta). These were eaten raw or dried for use in winter soups.

After the gardens had been thoroughly weeded, the village prepared for the summer hunt that would take them away from their village for several weeks. A successful bison hunt gave the Mandans a good supply of protein to set aside for winter. In addition, the Mandans also fished and hunted deer and small game.

As the summer days grew shorter, the crops began to ripen. Squash was harvested first. It was sliced and strung on poles to dry. Before the corn was harvested, the women again performed the corn dance. Each woman carried a whole stalk of corn and sent prayers to be carried by birds flying south to the Woman Who Never Dies. Each woman made a sacrifice of something she valued to honor the Woman Who Never Dies.

Women grew several different varieties of corn. Some types of corn were eaten fresh, others were dried on the cob, and some were removed from the cob and pounded into flour. After a successful harvest, there were between 800 and 1,000 bushels of corn stored in the village earthlodges and cache pits.

Early fall was the time for another bison hunt. After the meat was brought back to the village and dried, the Mandans prepared to move to a winter village. Winter villages were located near trees for shelter from wind and snow. Winter houses were built on the lower river bank and were usually destroyed by spring floods.

For the Nu’eta, winter was a time for story-telling. Many stories could be told only in the winter, and some could be told only by certain people. During the long dark days, winter count keepers re-told the tribal history. Some people had the right to tell origin stories. Listening to the stories, children learned all about their tribe’s history. Often a story-teller was honored with a gift from those who wanted to listen to the story. The story-tellers kept the stories in their memories; they were not written down until the 20th century. As the story-teller grew older, he or she would teach the stories to a younger person who became the next keeper of the winter count. In this way, the stories were preserved for hundreds of years.

Winter was the time to make new tools, weapons, and clothing. The man chosen to be winter chief led the village in ceremonies to encourage the bison to return to the village. Many people fasted and made sacrifices to help bring the bison back.

There were many villages along the Missouri, the Heart, and the Knife rivers where the Mandans lived in close communities. Each spring, in each village, the cycle of village life began again.

Why is this important? The village life of the Mandans followed a cycle that brought together their economic interests (hunting, gardening, trading), family life (creating families and raising children), and spiritual practices. All of these activities involved all the people of the village. Each person contributed according to his or her ability.

No one knows why the Mandans left Huff Village so soon after they built it. Other villages lasted for hundreds of years. Something changed, but we don’t know if the river threatened the village, if enemies attacked, if a disease came to the village, or if the people of Huff decided to join another Mandan village. However, village life based on the seasons continued on for another 400 years.