The Mandans and Hidatsas acquired horses at about the same time as the Lakotas did, around the middle of the 18th century. Like the Lakotas, the Mandans and Hidatsas made a place for horses in their culture. They found that horses were very useful for hunting bison and allowed them to travel much farther in search of bison herds. Horses did not change traditional village organization, but the acquisition of horses became an important “calendar” date. Events were identified as having happened before or after the tribes acquired horses.

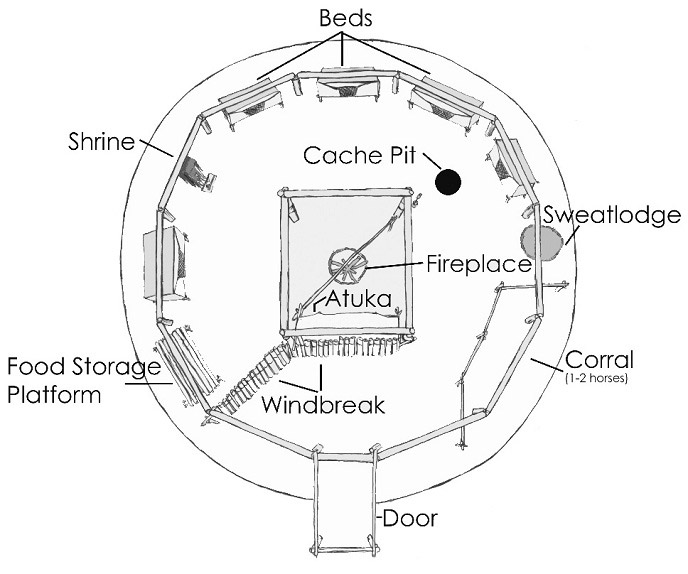

Horses were so important that they soon became integrated into many village traditions. Both men and women owned horses. However, women owned mares and foals while men owned stallions and geldings. Women had horses for riding and horses for carrying burdens. Men’s horses were trained for hunting or war. Horses trained for war and bison hunting were often kept inside the family’s earthlodge. (See Image 12.)

Mandan men acquired horses through raiding the herds of their enemies, but women acquired horses through certain family or clan relationships. A young man paid respect to a woman of his family or clan by offering her horses. When a young man went on his first horse raiding expedition, he gave the horses he captured to his eldest sister. This was a way of honoring his sister. If his sister was already married, she extended that honor by offering the new horse to her husband. If a young man struck his enemy while capturing horses, he would be given a new name by an elderly woman of his father’s clan. The young man paid the woman for this honor by giving her horses.

Horses were also important in arranging a marriage between young people. The Mandans had several systems for arranging a marriage. In one form of marriage, a young man’s family found a young woman who would make a suitable wife for their son. The man’s parents offered horses to the parents of the young woman. If the woman’s parents agreed that the young man would make a good husband for their daughter, they accepted the horses. The bride’s parents then gave the horses to their sons, who honored their sister (the bride) by giving the horses to her. The bride offered the horses to the father of the young man she was going to marry. In this exchange, both families acknowledged their approval of the marriage and showed respect to each family.

Mandans and Hidatsas considered horses to be a sign of wealth. (See Image 13.) The trading of horses between the families symbolized to the bride’s family that the young man came from a respectable family with enough resources to provide well for the young woman and her future children. The young man’s family offered enough horses (wealth) to demonstrate to the bride’s family that they held the young woman in high esteem.

Horses did not come to the Mandans and Hidatsas without some notable problems. Horses like to eat young plants and corn at any stage of growth. Horses had to be kept out of the large gardens where the women of both tribes raised corn, squash, beans, and sunflowers. Women usually erected platforms in the garden where they or their children watched over the growing crops and kept horses and other garden-raiding animals away. Horses also needed feed in the winter, especially when the snow was too deep for them to reach the grass. Usually cottonwood or willow bark served as winter feed, but finding and carrying winter feed to the horses added extra labor to ordinary winter chores. (See Document 1.)

Document 1. Maxidiwiac Speaks of Horses

Maxidiwiac (1839-1932), also known as Buffalo Bird Woman, was a Hidatsa woman. Like other women of her tribe, she maintained a garden. She explained gardening to Gilbert Wilson around 1915, when she was a very old woman. Gilbert Wilson wrote Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden after his long conversations with Maxidiwiac (Mah HEE dee WEE ah) about the gardens of Hidatsa women.

Buffalo Bird Woman and other Hidatsa and Mandan women used corn stalks to feed horses, but also had to prevent horses from destroying the gardens. In the following paragraphs, taken from Gilbert Wilson’s Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden, Maxidiwiac describes how Hidatsa gardeners adapted their gardening methods to horses. Source: http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/buffalo/garden/garden.html#XI

Acquiring Horses

At the very first it is true, we did not own ponies; but we soon got them. I think my tribe obtained ponies from the western tribes. In my own youth we Hidatsas got many of our horses from western tribes, especially from the Crows. . .

Feeding Horses from the Garden

In the early part of the harvest season, when we plucked green corn to boil, we gathered the ears first; afterwards we gathered the green stalks from which the ears had been stripped. These stalks with the leaves on them we fed to our horses, either [outside] the lodge, or inside, in the corral.

We commonly husked our corn, as I have said, out in the fields, piling up the husks in a heap. After the corn was all in, we drove our horses to the field to eat both the standing fodder and the husks that lay heaped near the husking place. Horses readily ate corn fodder, and by the time spring came again, there was little left in the field; not only were the husks devoured, but most of the standing stalks were eaten off nearly or quite to the ground.

Okĕi'jpita. . . This is a small ear that sometimes appears at the top, on the tassel of the plant. Okĕi'jpita ears, if large enough, we gathered and put in with the rest of the harvest; but smaller ears of this kind, hardly worth threshing, we gathered and fed to our horses. Sometimes, if the harvesters were in haste, these ears were left in the field on the stalk; a pony was then led into the field to crop the ears.

Protecting the Gardens from Horses

Horses did not trouble us much, as we did not permit them to graze near our garden lands; they were pastured on the prairie.

We always had fences around our fields as long ago as I know anything about; and I have heard that our tribe had such fences in the villages they built at the mouth of the Knife River, to protect their fields there from their horses. Such, I have heard, has been our Indian custom since the world began.

I think our fences stood twelve or fifteen feet away from the cultivated ground, as I pace it here on the ground. I know no reason why they were run thus, except as I have said, to keep the horses from nibbling the corn. You see, fifteen feet is quite a little distance; and the fence could have stood closer to the cultivated ground and still been far enough away to keep the horses from nibbling the crops. All I know is that it was a custom of my tribe, and I always followed this custom if I had a fence to build.

Pacing it off here, on the ground, the length of the stage was, I think, about so long–thirty feet. Its width was about thus–twelve feet. From the ground to the top of the stage floor was a little higher than a woman can reach with her hand, or about six feet, six inches; there were horses in the village, and the stage floor must be high enough so that the horses could not reach the corn.

The season for watching the fields began early in August when green corn began to come in; for this was the time when the ripening ears were apt to be stolen by horses, or birds, or boys.

Using Horses for Carrying Burdens

In the fall, when we went to our winter lodges, corn, squash, beans, and whatever else was needed, we loaded on our horses and took with us. As soon as we came to our winter lodge we made ready a cache pit at once and stored these things away.

Fertilizing the Gardens

We Hidatsas did not like to have the dung of animals in our fields. The horses we turned into our gardens in the fall dropped dung; and where they did so, we found little worms and insects. We also noted that where dung fell, many kinds of weeds grew up the next year.

We did not like this, and we therefore carefully cleaned off the dried dung, picking it up by hand and throwing it ten feet or more beyond the edge of the garden plot. We did likewise with the droppings of white men's cattle, after they were brought to us. . . .

I do not know that the worms in the manure did any harm to our gardens; but because we thought it bred worms and weeds, we did not like to have any dung on our garden lands, and we therefore removed it.

Why is this important? Horses brought significant changes to the Mandans and Hidatsas, but horses did not change the fundamental organization of the two tribes. Although horses also gave the Mandans and Hidatsas greater mobility, the two tribes continued to live in permanent villages. The Mandans and Hidatsas, like the Arikaras who joined them later, incorporated horses into their long-standing traditions.