Introduction

The Spirit Lake Reservation, formerly Devils Lake Sioux Reservation, is located in north central North Dakota. The people of Spirit Lake are often called Dakota “Sioux,” a term dating back to the 17th century. “Dakota” means “friends” or “Oyate”—“the people.” The term “Sioux” is a corrupted version of an Ojibway-Algonquian term “Naud-owa-se-wug,” meaning “like unto the adders.” The term was later corrupted resulting in the retention of the syllable that sounds like “Sioux.” (Meyer, 1967, 1993) However, the Ojibwa always called the Dakotas “A-boin-ug” or “Roasters.” (Warren, 1984) The Dakota at Fort Totten are called the Mni Wakan Oyate —“the people of the Spirit Water.”

White ethnographers’ interpretations of Dakota origin narratives place the Dakota origin in many eastern parts of the United States. These narratives are many and are well documented. However, they are not Dakota beliefs. These documents can be found in Indian studies departments or in the Minnesota Historical Society archives. However, recent findings in the Granite Falls and Browns Valley Man archeological sites and Waconia evidence confirm that aboriginal ancestors of the Dakota lived in Minnesota from 8,000 to 10,000 years ago.

According to Dakota oral history, the Dakota believed they were always in the area around the Minnesota River at Mille Lacs Lake. According to Dakota philosophy, the belief is that all living things originated from a great mysterious creator (God). In this philosophical context, the origin of the Dakota comes from the Creator and is a mystery—a truth only the Creator knows. If the Creator should want his people to know this, he would surely give them a sign. Dakota oral historians and holy men living in Dakota communities and reservations may share this information.

Of the seven original council fires of the great Dakota Nation, the two that make up the “Mni Wakan Oyate” (the people of the Spirit Water) are the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands. While the term Santee (Isanti) has been applied by non-Indian writers to both the Nakota and Lakota and all the Eastern Dakota as a group, the word Santee or Isanti only applies to the Bdewakanton, Sisseton, Wahpeton, and Wahpakute. Two treaties were made in 1851, one at Traverse Des Sioux with the Sisseton-Wahpeton and one with the Isanti (Bdewakanton Wahpakute) at Mendota (different bands). Therefore, the term Santee is not used in this guide when referring to the Spirit Lake people.

When the Sisseton and Wahpeton took possession of the land on the present-day reservation, there was a group of the “Cut Head band” of the Ihanktowana (Yankton) Dakota living in the Grahams Island area, as were many mixed bloods, Métis, and workers for the cavalry. The Cut Heads integrated and became a part of the Spirit Lake people.

In the early part of the 1700s, the Dakota occupied nearly the whole region of what is now Minnesota, except an extreme northern part, which had long been occupied by the Cree and Ojibway people. Before the time of contact between white explorers and the Dakota in the upper Mississippi Valley, the Teton Dakota moved onto the prairies and the Black Hills area. The Great Dakota Nation formed a political alliance known as the Seven Fireplaces, or Council Fires, or Oceti Sakowin. (Meyer) The Oceti Sakowin was a confederation similar to that of the Iroquois confederacy. The difference between the Iroquois confederacy and the Oceti Sakowin is that the Dakotas were culturally similar kinship groups, bands, or families which established social and political rules to govern themselves. These people were similar in their language and culture in their woodland’s environment. Later they became more distinct as they moved and adapted to the environment of the plains.

Dakota Migration

Throughout the 1700s the Dakota bands moved westward, one by one, onto the open plains. Some of them may have left the forest in search of game or other food. Many were pushed out by the Ojibwa, who were stronger because they had obtained guns from French traders and explorers, while the Dakota still had bows and arrows. By the mid-1700s, it is believed that small bands of Teton had crossed the Red River and were exploring the western plains.

History suggests that the many tribes were once historically connected or may have shared the same language of the great Dakota Nation. Those tribes were the Mandan, Crows, Winnebago, Omaha, and Iowa. (Hill, 1911) The great Dakota Nation was divided into three dialects and seven major bands. The Eastern Dakota, speakers of the Dakota or “D” dialect, comprised four bands: the Mdewakanton, Wahpeton, Wahpekute, and Sisseton. The Middle Dakota, speakers of the Nakota or “N” dialect consist of the Yankton, and Yanktonai. The Yanktonai, who before the 1800s were living in what is now the southern two-thirds of Minnesota, had moved into southern North Dakota, eastern South Dakota and parts of Iowa and Minnesota. The Western or Teton Dakota, speakers of the Lakota or “L” dialect, were the largest division with seven bands: Blackfoot, Two Kettle, Miniconjou, Hunkpapa, Brule, Sansarc, and Oglala.

The Dakota of Spirit Lake in North Dakota comprise two of the Bands of the Eastern Dakota: the Wahpeton, the Dwellers Among the Leaves and the Sisseton, the People of the Ridged Fish Scales. Other Dakotas include the Wahpekute, the Shooters Among the Leaves and the Mdewakanton, the Dwellers Among the Spirit Lake (Mille Lacs Lake). Kappler calls these the Sioux of the Leaf, the Broad Leaf, and those who shoot in the Pine Tops. (Kappler, 128–129)

Sub-Bands of the Sissetonwan

- Wita Waziyata Otina (North Island Dwellers) North Island is in Lake Traverse. Ohdihe (Falling headfirst)

- Basdecesni (Those who do not split the buffalo backbone.) Itokahtina (Dwellers at the south) an island in Lake Traverse.

- Kahmiatonwan (Village at the bend) Cansdacikana (little place bare of wood) • Keze (Barbed)

- Cankute (Shoot at trees)

- Tizaptan (Five Lodges) The Redfox and Young Families

- Kapoza (Light baggage)

- Abdowapushkiyapi (They who dry meat on their shoulders) Most of the original allottees in the Mission District belong to this band.

Sub-Bands of the Wahpetonwan

- Inyanceyaka Atonwan (Village at the rapids)

- Takapsintonwanna (Those who dwell at the Shinny (a game) ground)

- WiYoakaotina (Dwellers on the sand)

- Otehiatonwan (Dwellers in the thickets)

- Witaotina (Island dwellers)

- Wakpa Atonwan (Village at the river)

- Cankagaotina (Log house dwellers) Hazelwood Republic

Sub-Bands of the Ihanktonwanna Upper–

- Canon a or Wazikute (Wood or pine tree shooters)

- Takina (Return to life)

- Siksicena (Bad ones)

- Bakihon (Gashers)

- Kiyuska (Law breakers)

- Pabaksa (Head cut oft) These were at Devils Lake but moved to Standing Rock when Agent McLaughlin was transferred.

- unknown

Lower—Hunkpatina

- Pute Temini (Sweating lips)

- Sunikceka (Common dogs)

- Tahuhayuta (Eaters of hide scrapings)

- Sanona (Rubbed white)

- Ihasa (Red lips)

- Itegu (Burnt faces)

- Pteyutesni (No buffalo cow eaters) Big Track from Crow Hill District was chief. (Ross & Haines 1973)

Contact

The first white man to come among the Dakotas was a French missionary, Father Louis Hennepin, at their primary village near Mille Lacs Lake in July of 1679. A census of the Sioux, taken by voyageurs in 1736, numbered the Sioux at 10,000. About 1750, the Santee Dakotas were expelled by the Chippewa from their traditional homes around Mille Lacs Lake. In 1766, English explorer Captain Jonathan Carver recorded and distinguished the organization of the Sioux between River Bands and Prairie Bands. (Meyer, 1993, p. 15)

Official relations with the Dakota began with the expedition of Lt. Zebulon Pike into the upper Missouri River region in 1805–1806. Early in 1805, Zebulon Pike was sent by the government to survey the upper Mississippi River for the United States. During this time, Pike recorded 21,675 Dakotas living in the region. Pike’s mission was to obtain cessions of land from the Indians to establish military posts and government-owned trading posts to protect the Indians from unscrupulous traders. His first contact was with the Dakota, with whom he held a council on September 23, 1805, at a village nine miles north of the Minnesota River. This council meeting was significant because it was the first treaty between the United States and the Dakota. Of the seven Dakota chiefs present at this council, only two signed the treaty—Little Crow and Wanyagyainajin (Sees Standing). (Meyer, 1993, p. 25) The Dakota ceded 100,000 acres of land to the United States in the region where the St. Croix and Minnesota Rivers join the Mississippi River. For this exchange of land worth $200,000, the Dakota immediately received $200 in presents and later received $2,000 from the United States.

By the late 17th century, the Dakota Sioux were heavily influenced by the French and were caught between the French and English in a struggle for power and the fur trade. Forts were established among the Sioux. The French attempted to civilize and make the Dakota dependent upon French goods. By inducing the Dakota to farm it would serve as a deterrent to continued intertribal warfare among the Dakota, Cree, and Chippewa. Further, settlers continued to move into the area because of the 1805 Treaty. Many Dakotas were allied with the English in the War of 1812. Another treaty was negotiated on June 1, 1816 with eight bands of the Sioux.

Treaties

The Treaty of Prairie du Chien

Lawrence Taliaferro was appointed as an agent for the Mississippi Sioux in 1819. By 1836, Taliaferro, believing the material and moral condition of the Sioux worsened with each passing year, proposed another treaty. By this time, many fur traders and missionaries lived among the Dakotas. Traders opposed this treaty because they wanted payment for uncollected debts owed them. Taliaferro, hoping a treaty would satisfy the traders, added a provision going directly to them. He further believed it would ease growing pressure to open the exploitation to timber resources.

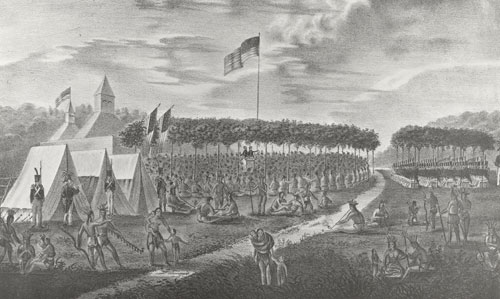

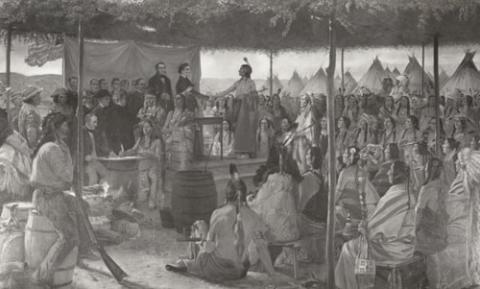

As a result, in August of 1823, the first Prairie du Chien Treaty Conference was held. The purpose of the treaty conference was to negotiate a general settlement to end intertribal warfare. The treaty brought together the Dakota, Chippewa, Menominee, Winnebago, Sac and Fox, Iowa, Potawatomi, and Ottawa. Generally, the negotiators believed the treaty would bring about peace. Many Indians, however, warned them it would fail. The Dakota notion of land was different and they believed that the land could not be divided because it was “used” by everyone. (Meyer, 1993, p. 40)

In the summer of 1837, Taliaferro was instructed to take a delegation of Sioux to Washington, D.C. The 26 Dakotas who went to Washington believed they were to negotiate a settlement between the Sacs and Foxes. However, the treaty called for a cession of the lands east of the Mississippi River. In return for the lands ceded, the United States promised to:

- Invest $300,000 and pay to the chiefs and braves annually forever an income of not less than five per cent,

- Apply one-third of the interest as the president saw fit,

- Pay the rest in goods, $5,500 annually,

- Provide relatives and friends of the tribe $100,000,

- Provide traders $90,000 for the debts of the tribe,

- Pay a $10,000 annual annuity in goods for 20 years, and

- Provide a sum of $8,250 annually for medicines, agricultural equipment, a physician, etc.

It was not until October 1837 that the Dakota received the first annuities. What did arrive was insufficient in quantity and inferior in quality. Additionally, some of the funds allocated for “education” were being given to missionaries, a provision to which the Dakotas did not agree. The slow delivery of goods, compounded by traders who marked up the price of trade goods, angered the Dakota.

This treaty went largely unrecognized because the tribes continued to hunt on the lands and the boundaries established by the treaty. As the game dwindled in the Minnesota River area, the Dakotas became more dependent on annuities.

During this period, missionaries were disproportionately represented among the Dakotas. The agent, Taliaferro welcomed them, believing that before the Indians could be “Christianized,” they needed to be “civilized.” Early missionaries, such as Stephen Riggs and Pond, went about their task of “civilizing.” A part of their efforts included the development of a dictionary of the Dakota language, in anticipation that the text would be useful once the language had died out. (Riggs, 1834 in Meyer, 1993, p. 54)

The 1851 Treaty at Traverse Des Sioux

James Doty, Governor of the Wisconsin Territory in 1841, believed the Sioux needed their own territory. He believed that by providing a permanent Indian territory, continued conflicts among the Sioux, Chippewa, Sacs and Foxes, and with other migrating eastern tribes would be limited. Doty’s plan included proposing another treaty, employing traders as government employees, and placing Henry H. Sibley in charge. The date for treaty negotiations was set for July 31, 1841. (Meyer, p. 74) This treaty was designed to provide an Indian territory within which the Dakotas were to reside. Tracts of land were to be set aside for each band on the left bank of the Minnesota River and each provided a school, agent, blacksmith, gristmill, and sawmill. The initial treaty was negotiated with the Sissetons, Wahpetons, and Wahpekutes. In August, he negotiated with the Mdewakanton bands, but Red Wing and Wabasha, their chiefs, refused to sell.

Lawrence Taliaferro, former agent for the Sioux, denounced the treaties, believing them to be a plot for the traders to gain complete control over the Sioux. Alexander Ramsey, who became governor of the newly established Minnesota Territory in 1849, urged the passage of the 1841 Traverse Des Sioux Treaties. The Senate rejected the treaties in August of 1842.

In the summer of 1851, Luke Lea, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, was sent to the Upper Mississippi Valley to help Alexander Ramsey negotiate the treaty. On July 18, at Traverse Des Sioux, the upper Sioux—the Sissetons and Wahpetons, were coerced into relinquishing all their claims in what is today Minnesota and a small portion of South Dakota. They were to receive $1,655,000 for which:

- $275,000 was to be given for chiefs to settle traders’ debts, and the cost of removal and subsistence for the people for one year. The Mdewakantons refused to sign these trader papers.

- $30,000 to establish schools, blacksmith shops, mills, and farms in the new area.

- $1,360,000 was to bear interest at a rate of 5 percent per year for 50 years for annual cash annuities of $40,000, $10,000 for goods and provisions, $12,000 for general agricultural and civilization purposes, and $6,000 for education.

A similar treaty was negotiated a few days later with the Mdewakantons and Wahpekutes at Mendota. The 1851 treaties were termed a “monstrous conspiracy.” According to Meyer:

All the standard techniques were employed by the commissioners. The carrot and the stick—and at least once the mailed fist—were alternately displayed, as the occasion seemed to demand. If the Indians asked for time to consider the terms offered them, they were chided for behaving like women and children rather than men. If they asked shrewd, businesslike questions, the commissioners uttered cries of injured innocence; surely the Indians did not think the Great Father would deceive them! If they wanted certain provisions changed, they were told that it was too late; the treaty had already been written down. The Indians were flattered and brow-beaten by turns, wheedled and shamed, promised and threatened, praised for their wisdom and ridiculed for their folly. In such fashion was their “free consent” obtained. (Meyer, 1993, p. 77)

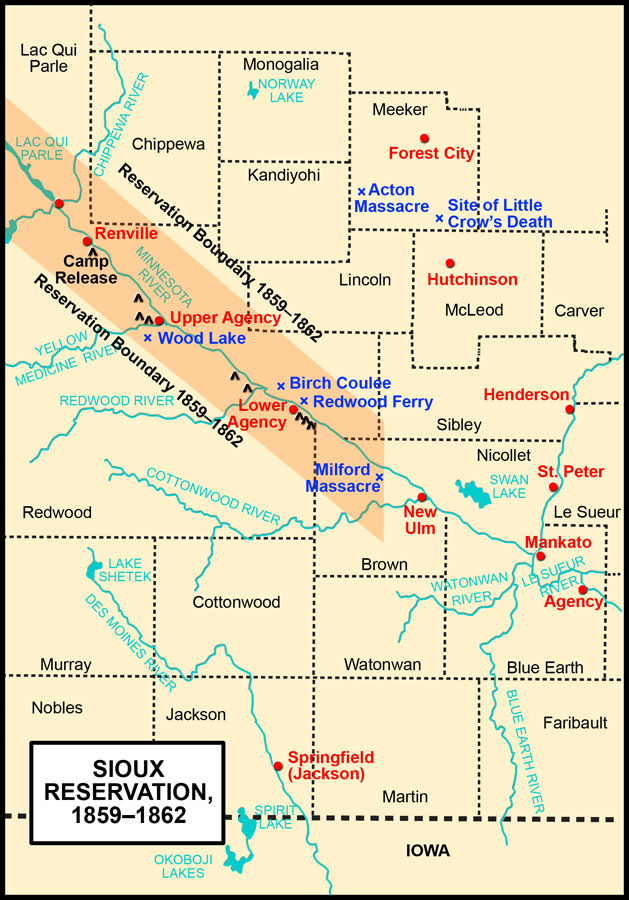

The Sissetons and Wahpetons gave up all their remaining lands except a narrow reservation extending 10 miles on either side of the upper Minnesota River. This treaty opened farming areas of Minnesota to settlement, and by the summer of 1862 the new territory was filled with settlers.

When the treaty arrived, the Indians demanded the promised money, which amounted to nearly $500,000. Knowing the money had been pledged to the traders, Ramsey turned to the traders and mixed-bloods to assist him by getting the Indians to sign “receipts” to legitimize the diversion of most of the cash to the traders. The traders received virtually all the cash, their share amounting to about $350,000.

When the treaty was ratified, the U.S. Senate decided the Indians did not need any land at all and struck out an important article which provided for a reservation on the upper Minnesota, extending 10 miles either side of the river down to the Yellow Medicine River. (Meyer, 1993, p. 80)

Ramsey, then Governor of Minnesota, and Henry H. Sibley, territorial delegate, fearing the Sioux would not accept treaties that left them with no home, persuaded the president to authorize the occupation of the reservation for five years.

By 1854–1855 military officers at Fort Ridgely reported that most of the food promised to the Dakota as a result of the treaties, never made it beyond St. Paul. The food that did reach the agencies was unfit to eat. The Dakota became increasingly frustrated. They were unable to maintain a living by farming. They were starving and even angry at the government for not sending “annuities” as promised. It was the general sentiment of a majority of the Dakota that the Great Father [president] had cheated them out of their birthright, and failed to keep the government’s promise that the Indians would no longer suffer from hunger and need.

The Dakota Conflict

Causes of the Great Dakota Conflict

Originally known as the Great Sioux Massacre, Minnesota or Sioux Uprising, a conflict arose which involved the Dakota and settlers in the Minnesota Valley. Under pressure from government agents and missionaries, many Dakotas were giving up traditional ways and adopting the ways of white men. Many cut their long hair, wore white man’s clothing, plowed the land and worshiped the white man’s God. A conflict was developing between the Dakota who clung to the old ways, and those who were adopting the new. Tensions were heightened by the policy of the government agents who would give food and supplies to the “Cut-Hairs” (Indians’ who had taken up farming) while denying them to those Indians who refused to become like the whites. Warriors, on the other hand, were resisting the pressure to change Dakota ways, and organized a soldier’s lodge and other secret societies to preserve Dakota tribal traditions.

From the Dakota standpoint, the causes of the outbreak of 1862 were many. Big Eagle, a Mdewakanton, gave this account:

There was great dissatisfaction among the Indians over many things the whites did. The whites would not let them go to war against their enemies. This was right, but the Indians did not then know it. Then the whites were always trying to make the Indians give up their life and live like white men —go to farming, work hard and do as they did —and the Indians did not know how to do that, and did not want to anyway. It seemed too sudden to make such a change. If the Indians had tried to make the whites live like them, the whites would have resisted, and it was the same way with many Indians. The Indians wanted to live as they did before the treaty of Traverse Des Sioux —go where they pleased and when they pleased; hunt game wherever they could find it, sell their furs to the traders and live as they could.

Then the Indians did not think the traders had done right. The Indians bought goods from them on credit, and when the government payments came, the traders were on hand with their books, which showed that the Indians owed so much, and as the Indians kept no books they could not deny their accounts, but had to pay them, and sometimes the traders got all their money. I do not say that the traders always cheated and lied about these accounts. I know many of them were honest men and kind and accommodating, but since I have been a citizen I know that many white men, when they go to pay their accounts, often think them too large and refuse to pay them, and they go to law about them and there is much bad feeling.

Big Eagle went on…

Then many of the white men often abused the Indians and treated them unkindly. Perhaps they had excuse, but the Indians did not think so. Many of the whites always seemed to say by their manner when they saw an Indian, “I am better than you, and the Indians did not like this. There was an excuse for this, but the Dakotas did not believe there were better men in the world than they. (Narrative Source: Jerome Big Eagle, “A Sioux Story of the War,” Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society 6 (1894): p. 312–400:) in Anderson & Woolworth, 1988, pp. 23, 24)

In 1862, there was a long, harsh winter, and crop failure among the Dakotas had been severe the previous year. As a result the Dakotas were starving. Rumors that the government was financially strapped (due to the Civil War) and might not make the promised treaty payment caused great unrest among the Dakotas. Amounting to $10 per person, the money was due the Dakota in late June, but had not arrived by mid-August. No one knew when the treaty payments might come. Adding to this hardship, the traders closed their stores and cut off credit to the Dakota until the treaty cash arrived.

In early August 1862, 5,000 hungry Dakotas gathered near Yellow Medicine (Pajutzee) River at the upper agency, to demand the food and supplies due them. After being refused by government agents, they stormed the agency warehouse and took 100 sacks of flour.

In order to calm the disturbance, a military detachment was called and soldiers pointed a cannon at the Dakota and the warehouse and threatened to blow it up. Little Crow, traditional Chief of the Dakota, intervened and urged that supplies be given, saying that the traders could be reimbursed by the government when the proper authorizations came through. (Coleman & Camp, 1988, p. 9) Little Crow said, “When men are hungry, they help themselves.” A trader named Andrew J. Myrick, refusing Little Crow’s compromise said, “So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry, let them eat grass.” The Indians sat in silence while Myrick’s remark was translated for them. When they heard it in their own language, they were outraged. Tensions were eased and fighting was averted when an agent sent for soldiers from nearby Fort Ridgely. Food was given to the Dakota to ease the growing tensions at the Upper Agency.

As the situation worsened, the influence of hereditary chiefs such as Wabasha and Little Crow declined, and the influence of more militant warriors became stronger. Many Dakotas blamed Little Crow for the 1858 Treaty that had resulted in the loss of half of the reservation that lay on the north side of the Minnesota River. This area was now filling with settlers. Although the million-acre parcel was worth at least $5 an acre, the Dakota received 30 cents an acre, most of which went to the traders.

The incident which started the Dakota Conflict began when four Dakota warriors Killing Ghost, Breaking Up, Brown Wing, and Runs Against Something While Crawling, hunting near Acton, Minnesota, took some eggs from a farmer. Although he was starving, the warrior was urged to return the eggs. Unwilling to do so, he was chided as a coward. Hearing this, the warrior smashed the eggs. The warriors moved onto the farm encountering the postmaster and engaged him in a shooting match. The postmaster, his wife, her son, and adopted daughter, and some new settlers were killed. The Dakotas, believing that the tide of events could not be reversed, became committed to win the return of their lands. From August 17 to August 25, 1862, under the leadership of Chief Little Crow, traditional chief, the Dakota took over trading posts and attacked settlers. When the conflict ended, 450 settlers and soldiers had been killed. While most of the attacks occurred in scattered settlements, the Dakota raided Fort Ridgely and New Ulm, hoping to clear the Minnesota Valley of its most important settlements. The Dakotas had failed to take either Fort Ridgely or New Ulm. Convinced from the beginning that the war could not be won, Little Crow and a number of followers retreated to the plains. (Coleman & Camp, p. 33)

On October 12, 1862, the Army under General Henry H. Sibley moved against the Dakotas, disarmed and put into chains all of the men. All together, they numbered 400. From October 25 to November 5, 1862, 392 cases were heard and death sentences were handed out to 307 Dakota warriors, that number was later reduced to 303. (Coleman & Camp, p. 33) On December 6, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln approved the execution of 39 Dakota warriors, later reduced to 38. On December 26, 1862, 38 Dakota warriors were hung in a mass execution at Mankato, Minnesota, the largest mass execution in this nation’s history.

Early sources termed the outbreak as one of the worst of American history because it sparked a series of Indian wars on the northern plains. It was not until the middle 1960s that researchers were able to sort out the causes of the conflict, and tell the Dakota’s side of the events. As a result, in 1987, one-hundred years after the Dakota Conflict, the Governor of Minnesota declared a “Year of Reconciliation” between the Dakota and the state of Minnesota.

Dakota Removal

On November 7, 1862, 1,700 Dakota women, children, and a few old men, were taken to an internment camp at Fort Snelling, Minnesota. Between April and May 1863, two boats carrying 1,700 people were shipped from Fort Snelling to St. Louis and Hannibal, Missouri, and then transferred by train and boat to what is now the Crow Creek Reservation in South Dakota.

In the spring of 1866, the federal government realizing that Crow Creek was unfit for habitation, moved the surviving 1,000 Dakota down the Missouri River, near the Niobrara River, to what is now known as the Santee Reservation. Other Sisseton and Wahpeton continued to hunt buffalo throughout the territory, but eventually settled near Devils Lake, which they called Spirit Lake, “Mni Wakan,” in the northern section of the region. These residents continuously occupied the Spirit Lake Reservation. Descendants of the Dakotas who fled to Canada remain today and many Dakotas travel there to participate in ceremonies with their relatives who reside on reserves.

Creation of the Devils Lake Sioux Reservation

After the Dakota Conflict of 1862, a few Dakotas remained in Minnesota. Most were driven or fled onto the plains of the Dakota Territory while others fled to Canada. The Mdewakanton and Wahpekute bands had been removed to the Santee and Crow Creek Reservations on the Missouri River. The Sisseton and Wahpeton bands, who had been mostly innocent of participating in the uprising, settled in northern Dakota.

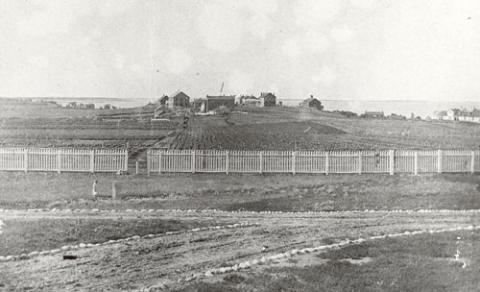

In February 1867, delegates went to Washington to make a new treaty. The treaty provided for the establishment of Lake Traverse, or Sisseton, Reservation in eastern Dakota, and another reservation south of Devils Lake for those wandering groups of Sissetons and Wahpetons who refused to come to Lake Traverse. The Cut Head band of Yanktonai Sioux was also included in the Treaty. (Pfaller, 1978, p. 6) When Fort Totten was built in 1867, there were no Indians in the immediate vicinity. The fort was established by General A. H. Terry, and named in honor of Brevet Major General Joseph Gilbert Totten, the late chief engineer of the U.S. Army. (DeNoyer, 1901, p.183)

The “acting head chief” of the Sissetons at Devils Lake was Tiowaste, or Good Lodge (called Little Fish). Although provided for in the Treaty of 1867, it was not until 1870 that William H. Forbes was appointed the first agent for the Reservation. It was believed that the Dakotas were induced to move to the fort because of the harshness of the winter and the degree of starvation amongst them.

During the 1870s, the number of Dakotas at Fort Totten grew from the few who gathered around the region, to more than 500. These Dakotas, because of their numbers, brought financial support and an agent to the military fort. The Dakotas, through the urging of the Agent John W. Cramsie, were seeing a measure of self-sufficiency during this period. They were cultivating their own farms and living in their own houses. The Fort, during these years, took up much of the reservation’s land, an issue of contention with the Dakotas. They saw their game depleting and the reservation lands assumed by the military fort. The gradual loss of bison, followed by a series of severe winters and droughts, an increased supply of annuities, caused the Dakotas dependence on the reservation system and the military fort.

The growth of the region became a reality with the creation of Creelsburg, a squatter’s town, which later became the community of Devils Lake. The military fort, in the late 1890–1891, considered an unnecessary expense, was closed by the government. Fort Totten was then turned over to the Superintendent of the Indian School at Fort Totten.

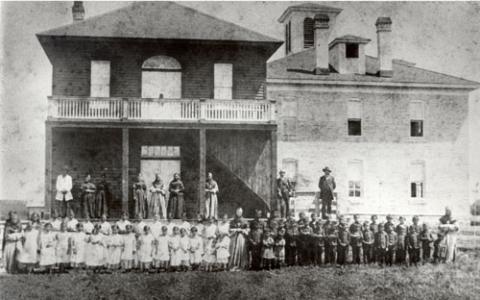

The Boarding School Era

Between 1878 and 1930, boarding schools for Indian students took roots. Several boarding schools in places like Carlisle, Pennsylvania and Hampton Institute, Hampton, Virginia were seen as a way to transform Indian people. Between the 1880s and the early 1900s, the government built a series of boarding schools on the newly established Spirit Lake Reservation. The boarding schools at Fort Totten had an unmeasurable impact on the culture of the Dakotas on the Reservation.

At the urging of Major Forbes, four Sisters of the Community of Gray Nuns of Montreal arrived on October 17, 1874, to begin teaching. They occupied and taught school in a small building erected for them by the Sioux people. This school became known as St. Michael’s Manual Labor School, and provided education from 1874 to 1890. Fifty children were taken to the school the first year, reluctantly, and twenty-five remained the whole year. (DeNoyer, 1901, p. 293) In 1890, the government abolished contracting with various bureaus such as the Catholic Bureau or the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, so the Gray Nuns began direct employment as teachers.

On February 16, 1893, the main building of the Old Mission burned down. The students, then numbering 96, were crowded into a smaller building, and the school continued in that manner until 1885. In 1890, the military abandoned Fort Totten and the post buildings were turned over to the agent as an industrial school. The mission school was then consolidated with the industrial school. In 1904, the Turtle Mountain Reservation was also placed under the administration of the superintendent at Fort Totten.

Consistent with the Quaker “civilizing” policy of the government, instruction for boys at the industrial school included harness making, tailoring, shoe making, engineering, carpentry, farming, gardening, and dairying. For the girls, instruction in cooking, sewing, fancywork, and nursing was provided. Boys over twelve years of age were required to attend the industrial school proper for the purpose of learning a trade. All the children were kept until they completed their course of study. Some were allowed to return home in the summer. (DeNoyer, p. 201)

In 1897, 270 students were enrolled at Fort Totten Industrial School. The curriculum focused on industrial training and the course of study included the carpentry, plastering, and plumbing trades. These were necessary for the upkeep of the school. By 1910, the school enrollment was 473 students, one-half of which were Chippewa and Métis children from North Dakota and Montana. In 1911, the enrollment was 400 students. Academic courses were reduced and more emphasis was placed on producing food and clothing because of reduced funds from the Indian Bureau. The school closed in 1917 because of deficits, and re-opened in 1919 with an enrollment of 313 students. Between 1919 and 1921, severe crop failures and hard times forced sending children attending Fort Totten schools from other reservations back to their homes. Between 1926 and the late 1930s, enrollments were large. It was not until the late 1930s and the early 1940s that Indian boarding schools across the country were closed, including the Fort Totten boarding school which closed in 1935. Relations between the agent and the Dakotas were relatively harmonious due largely to the fact that Agent Forbes did not try or interfere with the traditional customs of the people. Agent Forbes died in the summer of 1875.

Impact of Federal Policy and Legislation

Allotment

In 1874, when the agency building was being built, the Indians were dispersed in five or six settlements, mostly in wooded areas. After a few years, they began to scatter over the reservation on individual farms, at the wishes of Agent Forbes. Reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs noted that progress in assimilating the Indians at Fort Totten was slower than at Sisseton. Agent McLaughlin, who took charge on July 31, 1876, encouraged the transformation by reducing the quantity of blankets issued and substituted clothing.

He even went so far as to issue only white blankets, which the Dakota almost had to use exclusively as bed covering. (Meyer, 1967, p. 229) The issuance of rations was a source of disagreement and resentment among the Dakotas. At Sisseton, some of the Indians objected to working for the annuities to which they were entitled under the terms of the agreements providing for the cession of their lands. With a continuing influx of settlers, the agent proposed surveying the reservation, which was met with great opposition. Immediately upon the passage of the General Allotment Act in 1887, Fort Totten Agent John W. Cramsie began the process of dividing the reservation consistent with the allotment policy of the government.

In 1883, a survey of reservation boundaries found a majority of non-Indians homesteading on 64,000 acres of land that belonged to the reservation. The U.S. government was not living up to its treaty responsibility to prohibit settlers encroaching on Indian lands. Nothing was done to remove the settlers or compensate the Dakota until 1891. Agent McLaughlin, as a part of the General Allotment policy, met with several adult Indian males and the federal government to discuss allotment of the reservation. They agreed upon the sum of $345,000 to cover the 64,000 acres and other wrongful land uses. (Kappler, 1902, Vol. III, p. 83) When the reservation lands were opened for sale to non-Indians in April 1904, Congress deleted the money owed the Indians and stipulated that the settlers pay for the land at the rate of $3.25 an acre. (Kappler, p. 85)

Allotment continued and by 1904, the Dakota, rather than being forced onto lands they did not want, chose allotments in the area of their camps and near their relatives. This resulted in the creation of certain communities. The Yankton settled in the Crow Hill area. The Sisseton and Wahpeton established the communities of Wood Lake, Tokio, and St. Michael. (Schneider, 1990, p.90)

The allotment acts severely reduced Indian-owned lands. Before allotment, Indian owned lands on the reservation consisted of almost 300,000 acres. This was reduced to 166,400 acres after allotment.

According to Agent Cramsie, from 1883 to 1889, the Dakotas were doing all of the actual farming on the reservation. Allotment in severalty was tragic for the Dakota. Starting in 1886, drought reduced crops raised by the Dakota, and in the seventies, grasshopper plagues contributed to massive crop failures ... “On account of rigidity of soil, unfavorable seasons, inexperience, and a multiplicity of causes.” (Commissioner of Indian Affairs Annual Report, 1881, p. 35) The Dakota slipped back to almost total dependence on government assistance. In 1893, they were living largely on parched corn and wild turnips.

Early 1900s

At the turn of the 20th century, the government’s civilizing policy to force the Indians at Spirit Lake and Sisseton into citizenship was disastrous. In 1905, the superintendent of schools reported that two schools on the reservation had an enrollment of more than 330 students. (Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1905, p. 278) The several day schools opened by the government failed to convince the Dakota to continue sending their children to school. In 1927 when the Grey Nun’s government employment ended, they built a new mission boarding school, the Little Flower School at St. Michael, North Dakota.

From the outset, the issue of language proved to be a problem. In 1887, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs required English to be used in all Indian schools. In the first place, the Dakotas were reluctant to send their children to these schools. One commissioner reported that parents, with justifiable cause, refused to send their children to the schools because they were ill-treated. The federal government realized that there was a growing problem in educating Indian children.

In 1928, a report was issued entitled “The Problem of Indian Administration,” better known as the Meriam Report. The findings of this report provided Congress and the Bureau of Indian Affairs with the basis for formulating policies affecting Indian education into the 1930s and 1940s.

The Dakotas, like most tribal people, believed that service in the military was a great honor and a responsibility. Like men from other tribes, when World War I began, a disproportionate number volunteered in the armed forces at home and overseas. Because of this action, Congress was left in a dilemma of how to deal with the Indians who were not then citizens. As a result, in 1919, Congress granted citizenship to those Indians who had participated in the war. The war affected the reservation as it did the general population. The economy and the social environment suffered greatly. In 1924, with the passage of the Snyder Act, or Indian Citizenship Act, all Indians were granted citizenship.

Indian Reorganization Act

By 1934, the Dakotas faced a crisis over the lack of land available to its members. Congress at the urging of John Collier, passed the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) known as the Wheeler-Howard Act. This piece of legislation was designed to ease the land situation by halting the sale of Indian lands by providing funds to buy reservation lands. The Act also provided economic support by establishing elected governments. The Tribe did not vote to adopt this IRA provision. In 1944, the Tribe did, however, draft its first constitution and bylaws. These were not approved by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs until February 13, 1946.

Throughout the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, economic and tribal self-sufficiency was an issue of primary concern. Reservation lands were so divided that it was impossible for most people to make a living by farming or ranching. Rather than providing the assistance necessary, the federal government promoted a policy of leasing Indian lands to non-Indians. In 1944, Indians worked only 12,628 acres of trust land, while non-Indians leased and farmed 27,879 acres. (Fine, 1951, p. 39) In spite of the poor economic situation on the reservation and the potential of relatively good pay, many Dakota had established a measure of self-sufficiency. Many families moved to the Red River Valley to work in the potato harvests. Some men farmed and worked to build day schools. They also worked in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) planting trees. The women cultivated large gardens.

Termination

Between 1952 and 1960 Congress, believing that many tribes were well on their way to self-sufficiency, enacted legislation to terminate the federal trust relationship between the federal government and Indian tribes. This piece of legislation served to significantly worsen the already severe economic conditions on most reservations, as well as on the Spirit Lake Reservation. During this period:

The Bureau of Indian Affairs dominated efforts of the tribes and community life revolved around the Bureau. Poverty was evident everywhere with employment possibilities practically nonexistent. Housing was poor and substandard, school dropout rates were high and children were sent away from friends and families to boarding schools because of isolated from public schools, poor living conditions, and transportation problems. Health problems were rampant and the average life span was only 40 years of age on most reservations. (United Tribes, 1985, p. 23)

Many families were provided with federal “relocation” assistance, and moved to cities such as Chicago and Minneapolis, to train for employment. While many people today still live in several large urban cities, most returned home.

Self-Determination

The period between 1960 and 1980 became known as the era of self-determination. In the early 1970s, a new Indian activism created a national awareness of the severe economic conditions that tribal governments and reservations faced. Without income sufficient to meet basic needs, training or jobs, the economic depression on the reservation worsened. With the assistance of North Dakota’s senior senator, Milton R. Young, the Sioux tribe entered into a joint venture relationship with the Brunswick Corporation to manufacture camouflage nets under contract with the federal government. With a fluctuating labor force, employment figures at the plant varied from 150 to 300 annually. The Sioux Manufacturing Corporation operated successfully, and from at its high, the plant completed contracts annually in excess of $60 million. Having completed its fixed participation period in the government’s minority small-business set-aside program, the company diversified. In 1986, Dakota Tribal Industries, a 100 percent tribally-owned company, was created and began the manufacture of military helmets and camouflage netting. In the late 1970s the tribe added an economic stimulus with the assistance of the U.S. Economic Development Administration (EDA), by establishing a small shopping center complex on the reservation. The shopping center featured a small cafe, laundromat, grocery store, and gas station. Because of the Tribe’s location to Devils Lake, Sully’s Hill National Game Reserve, and the declaration of the old military fort at Fort Totten as a national historic site, tourism became a positive factor for the community.

From the period of allotment through the 1930s, millions of acres of Indian trust land went out of Indian ownership. Because few Indians made wills and died without providing for the division of land, a problem of “fractionated heirship” arose. As the years progressed, claims for shares were so numerous and small, that it virtually made land lease payment administratively impossible. In 1983 Congress passed the Indian Land Consolidation Act, to deal directly with this situation on the reservation. This Act permitted tribes to receive ownership of small shares of land (if that land represented less than 2 percent interest and had earned less than $100 in the previous year) from deceased tribal members. Because of the “checkerboard” pattern of Indian and non Indian land ownership on Indian reservations creating numerous jurisdictional problems, the Act provided an opportunity for tribes to reacquire portions of their reservation land base.