Arikara is a word that European Americans applied to a group of people who call themselves Sahnish. Throughout the historical era, they were referred to in writing as Arikaras, Arikarees, or Rees.

Before the time when the Sahnish came into contact with European Americans, several small bands joined together for protection. The Sahnish were closely related to Pawnees who lived in the Nebraska area, but the Sahnish followed their spiritual leader who directed them to move northward along the path of the Missouri River. They formed three villages along the Niobrara River, near where it empties into the Missouri River in present-day northeastern Nebraska. By 1723, the Arikaras had moved into the land now called South Dakota. (See Image 1.)

The French explorer and trader, Verendrye, found Sahnish villages near the mouth of the Cannonball River in 1743. There were more Sahnish communities to the south. Lewis and Clark met the Arikara near the mouth of the Grand River (northern South Dakota) in 1804. The Sahnish continued to move northward according to the plan given them by their sacred spirits, Chief Above and Mother Corn.

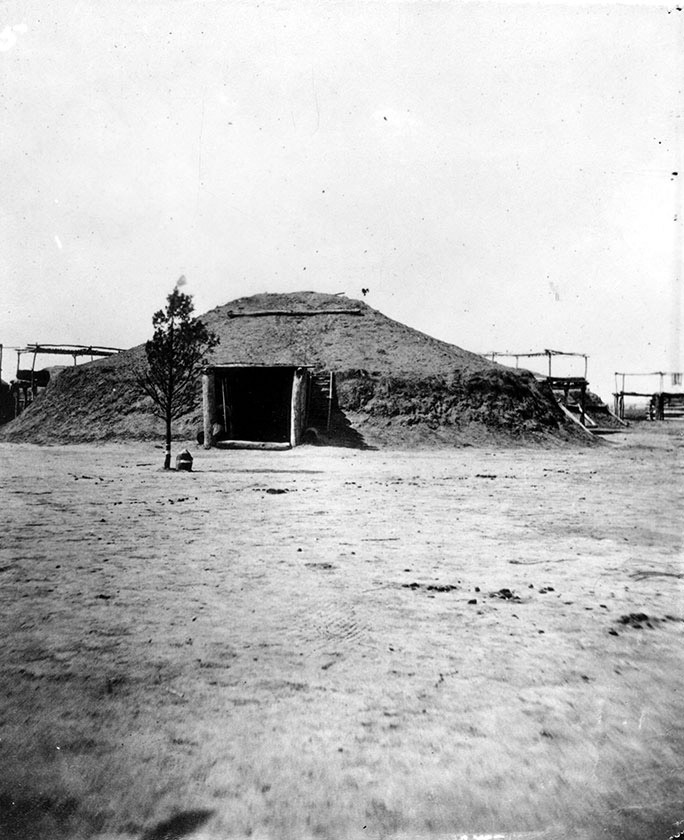

The Arikara lived in earthlodges that the women built from logs and earth. At the top of the lodge was an opening where smoke could escape and light could enter the lodge. The beds were built along the outer walls, and a sitting and cooking area was near the fire pit in the center. Each lodge had an altar where sacred objects were kept.

Sahnish women gardened outside the palisades of the village. They raisedcorn, squash, and beans.Corn, squash, and beans are often called the “three sisters” of gardening. These plants provided excellent nutrition. The dark yellow squashes contained a rich source of vitamins, particularly Vitamins A and C. Corn and beans contained calorie-rich oils that were very important in late spring when food supplies were dwindling. The Sahnish and other gardening tribes also hunted bison which provided protein and B vitamins. However, these tribes could also rely on corn and beans for good quality protein. Though neither corn nor beans contains the complete proteins that humans need, when eaten together the two vegetables form complete proteins. These garden foods were supplemented with wild berries, plums, and plant roots such as prairie turnips. Men hunted bison and other large game animals. Women dried and tanned the hides and made hides, bones, and other organ parts into useful household goods. (See Image 2.) For instance, a bison bladder was washed, dried, and fitted with a rawhide handle. It was then used as a bucket to carry and store water.

A good meal in an Arikara home was roast bison meat with a stew made of corn, beans, and bone marrow. Women prepared the meals from either fresh meat or meat that had been dried. The corn and beans were dried for later use, too. Women also made pottery and baskets and took care of their children.

Marriages were usually arranged by families, but a woman could not be married against her wishes. The couple became “engaged” when the man’s family presented gifts to the woman’s family. If the gifts were accepted, the marriage could proceed. Once married, the young man moved into his wife’s family’s lodge. A man could marry more than one woman if he was able to support all of them.

The social organization of the village was based on the kinship system. Children called their biological mother and her sisters, “Mother.” A man referred to his father’s sisters as “Mother.” Mothers cared for the children of their sisters and brothers as though they were their own. As young men grew up, they learned the skills necessary for war and spiritual leadership from older members of the special societyMany American Indian tribes had special societies for both men and women. The young men and women in each society socialized while learning the skills, stories, and religious practices of older men and women. Some societies had a particular interest such as war or sacred ceremonies. Other societies organized social activities. they joined. Young men referred to the leaders of their societies as “Father.”

Each village had a leader chosen for his military ability and highly valued qualities of wisdom, generosity, and moral behavior. The chief and his assistants held the highest level of leadership among the Sahnish. Members of the Piraskani society were men and women of good moral character who held a secondary position of leadership. Outstanding warriors were also expected to be leaders.

In spiritual practices, the Arikaras looked to Mother Corn to teach them how to live on earth. Mother Corn took the concerns of the Arikaras to Chief Above. The Arikaras believed that all things on earth had a spirit. An Arikara might enter upon a vision quest and receive instruction and protection from an object such as a stone, a tree, or a deer. Throughout the seasons, the Arikaras held ceremonies to promote success in hunting and gardening. In addition, individuals held ceremonies to mark important events in their lives. (See Image 3.)

In the 1837, the Arikaras endured, for at least the third time, a smallpox epidemic that killed nearly one-half of the tribe. After the epidemic had run its course, the Arikaras moved into a village near Fort Clark on the Missouri River. In 1856, another smallpox epidemic weakened the tribe further. The Lakotas pressured the weakened Arikara until they had to move again. In 1862, the Sahnish moved into Like-a-fish-hook village where the few surviving Mandans and the Hidatsas lived. (See Image 4.)

Why is this important? There are many cultures in North Dakota. All cultures share some elements of society with all other cultures. In common with other peoples, the Arikaras had a political order (chiefs and other leaders), an economy (hunting and gardening), and a social order (families and kinship system). However, Arikara language, religion, clothing, and other customs grew from the tribe’s unique history and experiences. In ordinary ways and in ways that were specific to their culture, Arikara community life provided everything the people needed for a good life on the Plains, including the ability to move to better or safer places when necessary.